You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Cycling and performance: what training structure really works?

How does the type of training you perform and your training volume affect cycling performance in the longer term? Andrew Sheaff looks at new research, which comes up with surprising answers!

There are three key factors that have long been recognized to influence endurance performance. These are: the quantity of oxygen that an athlete can consume to create energy (VO2max); the percentage of that VO2max that can be sustained without muscular fatigue setting in (lactate threshold); the ability to use energy efficiently (known as ‘economy’). All of these directly influence performance but the ability to create lots of energy and use that energy efficiently is key. More recently, a fourth factor - the ability to maintain high levels of these factors during actual competition (known as ‘durability’) - has also been identified, as we’ve covered in recent articles.

The relevance of oxygen

Since VO2max determines the maximal amount of oxygen that can be turned into energy, it sets the ceiling for energy production. As a result, there has been a lot of interest in improving it. The higher it is, the greater the potential for performance. Obviously, coaches, athletes, and researchers have a lot of interest in finding the best approach to improving this key quality.

In cycling, this is particularly true because cyclists can do a lot of work during training (thanks to the smooth and impact-free nature of cycling), so they have a lot of options as to how they can organize and execute their training. There are many different approaches to designing and organizing training. One of those approaches is polarized training, where there’s an emphasis on high and low intensity sessions, with less training in between. In contrast, non-polarized training has a more even distribution of training intensities.

While there’s solid evidence for both approaches, it’s not immediately clear if training interventions focusing on either a polarized or non-polarized training distribution preferentially impacts VO2max or performance. It’s also not clear just how much volume is necessary to improve VO2max. While VO2max is not the only aspect of performance that matters, it is a critical one. The more that’s understood about how to improve it, the easier it is to for coaches and athletes achieve their desired results.

New research

A group of Australian researchers has sought to clarify the most effective approach for improving VO2max in cyclists(1). Rather than conducting their own study, they sought to aggregate all the previous literature investigating VO2max in cycling. The authors scoured the literature to find studies that could be relevant to their objective. Rather than simply using any training study involving cyclists, they set some strict criteria to ensure that only the most relevant studies were used in their analysis. There were three main criteria that the authors used for inclusion:

- Firstly, the studies needed to have before and after testing of aerobic fitness or aerobic performance, allowing the researchers to assess the degree to which VO2max was improved by the training.

- Secondly, the subjects included needed to be either within 20% of world-leading performance levels or within 20% of world-class physiological fitness. As this study was investigating VO2max, the authors set cutoff points of 59.0 and 54.5ml/kg/min for males and females respectively, below which study athletes were excluded.

- Thirdly, the studies had to be peer reviewed and published in the English language. Peer reviewing ensured that the studies were of suitable quality, and the requirement for English ensured that no issues with translation were present.

The second point above is a particularly important point because training studies performed with lower-level (amateur/recreational) athletes can often be misleading since a much wider variety of training stimuli can result in improvement in these individuals. In this study however, the authors wanted to focus on what leads to improvement in already well-trained and high-performing athletes.

Types of training

After screening all the potential studies, 44 met the inclusion criteria. As assessing the impact of training distribution was one of the primary outcomes being investigated, the next step was to classify the various studies based upon the types of training interventions that were included in the study. The authors classified a training intervention as polarized based upon ‘the inclusion of both low-intensity training as well as high-intensity interval training’. Low intensity, long-duration training is a key component of a polarized training distribution, so its presence was a necessity. For inclusion, a study had to explicitly contain low-intensity training. If that wasn’t the case, it was also acceptable if the subjects of the study continued to perform their regular, non-interval based training.

In terms of interval training (the intense component of polarized training), the authors required that the intervals be less than five minutes duration and where the subjects were attempting to perform them as fast as possible. Alternatively, the intervals could simply be performed at intensities greater than maximal lactate steady state (above lactate threshold). If the intervals included in the study did not meet these criteria, and likely consisted of less than maximal intensities, the training distribution was then considered non-polarized. A training categorization of ‘unclear’ was used if these criteria weren’t reported, or there was no clarity as to what was done or how it was done.

Number crunching

Once training distributions were assessed, it was time to start crunching the numbers. The two primary outcomes that the authors were interested in were VO2max and time trial performance. As we discussed early, VO2max is one of the primary drivers of performance, and as such, it’s a critical physiological target in training. But while VO2max is key determinant of performance, it is not performance itself. It is one of several important factors influencing outcomes. Thus, it’s critical to evaluate the impact of training interventions designed to improve VO2max on actual performance outcomes. While it’s likely that improvements in these outcomes will move together, that cannot be taken granted.

With these outcomes in mind, the researchers analyzed how training distribution impacted both VO2max and time trial performance. They wanted to understand if either polarized or non-polarized distributions had a preferential impact on these outcomes. Of course, it’s not just the training distribution that might matter. How much work is performed can also potentially impact outcomes. As such, the authors analyzed how training volume influenced changes in VO2max and time trial performance.

Finally, different training interventions are not necessarily the same length. Some studies lasted for four weeks, and some studies for four months. The authors wanted to understand if the duration of the training intervention had an impact on either VO2max or time trial performance. Again, while the two outcomes are related, they are not the same, and it’s possible that there is a differential effect of the duration of training intervention on these two outcomes.

What they found

When all the numbers were run, unsurprisingly, it was clear that training improved VO2max. Perhaps more surprisingly however, there was no statistical difference between the different training distributions and the degree of improvement. There was a small advantage for the polarized group, but it did not reach significance (ie it could have occurred as a result of a statistical blip rather than as a real effect). Similarly, training was shown to increase time trial performance, but there was also no advantage either way for polarized vs. non-polarized training interventions.

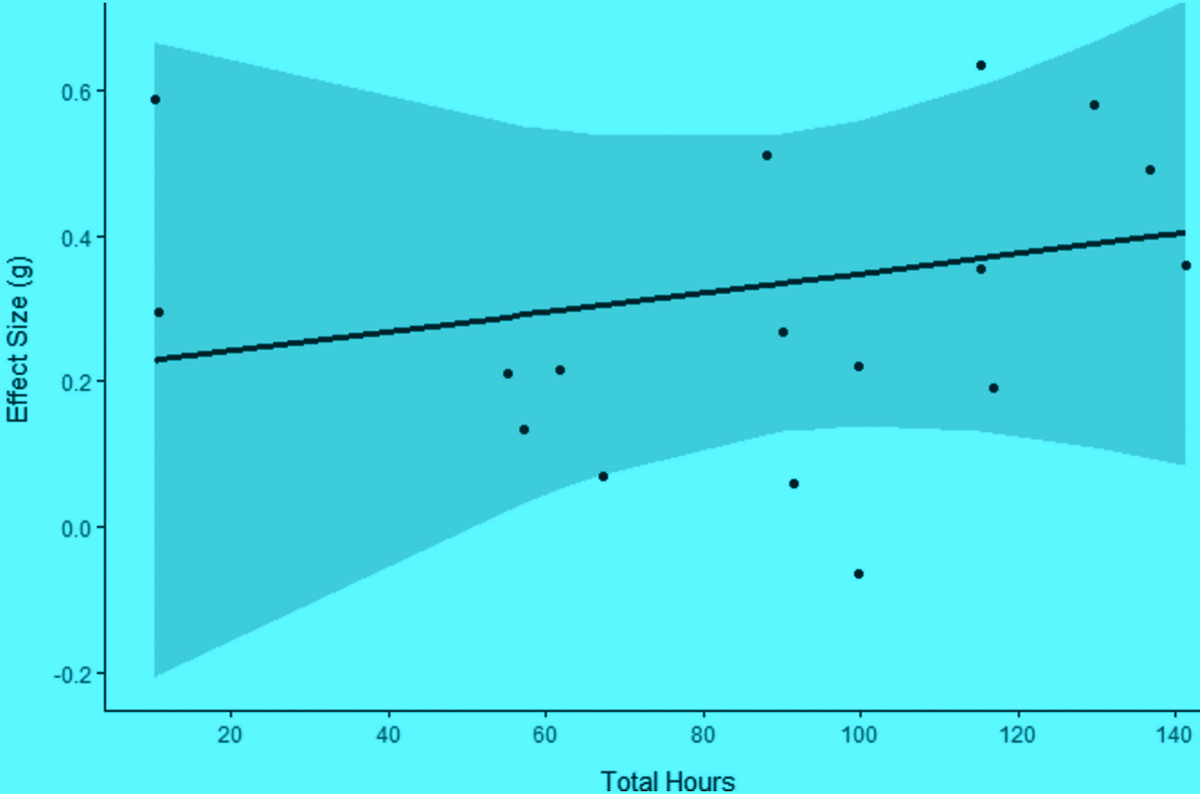

When it came to training volumes, there was no clear relationship between training volume and performance (see figure 1) or training volume and VO2max (figure 2). This was true when the weekly training volume was considered and when the total volume across the entire intervention was considered. Interestingly however, when it came to the duration of the intervention, longer interventions were related to great improvements in VO2max and time trial performance.

Overall, these results may seem a little puzzling, so the authors offered some potential explanations. First, the highest training volumes are often seen in the highest-level athletes, and these athletes tend to improve the least due to their already very high levels of fitness. This may obscure the relationship between volume and improvement. Secondly, it’s possible that there is a ‘ceiling effect’, beyond which further increases in volume simply don’t lead to larger improvements. Thirdly, higher volumes almost always necessitate lower training intensities, whereas higher training intensities are important for improving VO2max. It may be that there are advantages of higher volumes, but they are offset by lower intensities.

Figure 1: Training volume and time trial performance

The graph shows a scatter plot with Effect Size (g) on the vertical axis and Total Hours on the horizontal axis. The data points are spread out with no clear pattern or strong trend along the line, which is nearly flat. The shaded confidence interval is wide and overlaps a lot, indicating uncertainty and variability. This suggests that as training hours increase, there isn’t a consistent or strong change in time trial performance (effect size), implying no significant association between the two.

Figure 2: Training volume and VO2max

A similar pattern is seen here; the data points are spread out with no clear pattern or strong trend along the line (also nearly flat). The shaded confidence interval is indicates a lot of uncertainty and variability, which suggests that as training hours increase, there isn’t a consistent or strong change in VO2max.

Practical advice for athletes

While this study may not tell you exactly what to do, it does provide insight into what matters and what doesn’t. First, it’s critical to be consistent with training, as longer interventions do matter. If you’re trying to improve your VO2max, make sure you allocate enough training time over a long enough timeframe to produce benefits. On the other hand, it appears that you have a lot more flexibility in terms of how you approach your training; whether you prefer polarized training or nonpolarized training, either can be effective for achieving your goals. It’s not the case that one a single training prescription is ‘better’ than the rest! Likewise, whether you’re able to perform higher or lower training volumes, it seems that both options can get you to where you want to go in the longer term. Provided you’re doing the right type of high-quality work, it’s possible to be more flexible in your overall approach.

It’s important to note that these results are specific to cyclists. And for cyclists, this research provides clear guidance as to what matters (consistency over a long period of time and the inclusion of high quality training sessions) and what doesn’t when trying to improve VO2max or time trial performance. But while the principles underpinning effective training are the same in all sports, the application of these principles may be different for other sports such as swimming, running and rowing, where different mechanics are at play. In running for example, the increased risk of injury when performing higher training volumes may preclude high mileage running for many athletes. For these other sports, this research should be considered more as a guide to what’s possible, helping athletes to consider how the findings could apply to their sport.

References

1. J Sci Med Sport. 2025 May;28(5):423-434. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2024.12.005. Epub 2024 Dec 20

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.