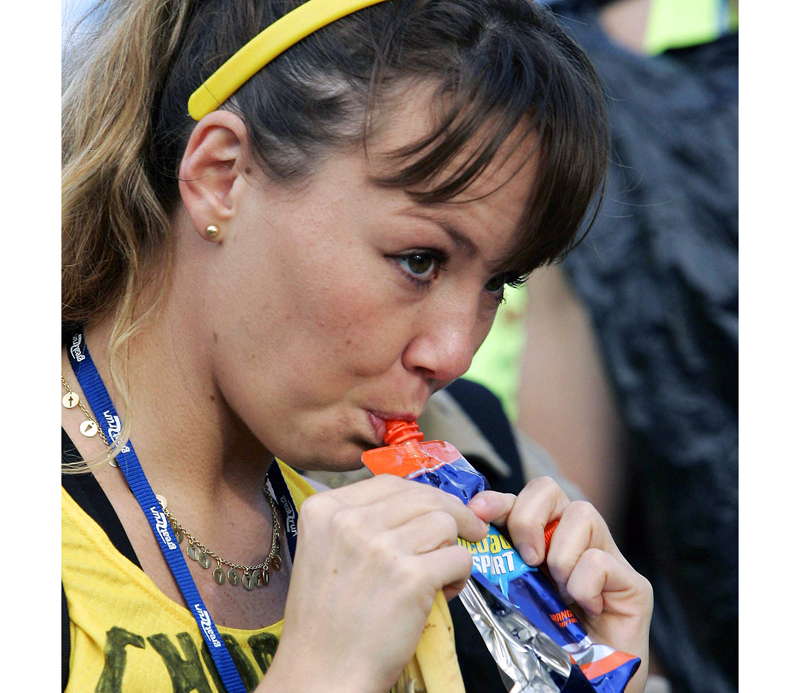

Carbohydrate drinks

Carbohydrates and perceived exertion

Does carbohydrate supplementation exert an ergogenic effect during marathon running? That is the question US researchers set out to answer in a study of 98 male and female entrants to the 1999 Charlotte Marathon and the 2000 Grandfather Mountain Marathon in Boone, both in North Carolina.The highly experienced (but non-élite) participants, ranging in age from 21 to 72, underwent a series of blood and anthropometric tests on the morning of the race and were then randomly assigned to one of two conditions:

- supplementation with a 6% carbohydrate drink, with each runner ingesting 650ml about 30 minutes before the start of the race and approximately 1,000ml at hourly intervals during the event;

- the same amounts of an inactive placebo drink, identical in appearance and taste to the carbohydrate solution.

Key findings for the two races combined were as follows:

- Race times for both the carbohydrate and the placebo group were slower than their personal bests of the previous year due to the hilly terrain of both these marathons. Although race times did not differ significantly between the groups, the placebo group was about 15 minutes slower by comparison with these earlier PBs than the carb group;

- RPEs during running did not differ significantly between the two conditions, although there was a non-significant trend towards a higher RPE during the later portion of the race with placebo;

- Runners in the carbohydrate group were able to run at a higher intensity – ie at a higher percentage of their maximum heart rate – particularly during the final 10km;

- Despite the similarity in RPE between the two conditions, there was a significant decrease in plasma glucose and insulin, concomitant with an increase in plasma cortisol and growth hormone, with placebo compared with the carbohydrate condition.

‘These findings suggest,’ they conclude, ‘that the attainment of a greater percentage of maximum heart rate at a given RPE can be attributable to a sustained supply of carbohydrate energy substrates to the exercising muscle.’

But they add: ‘During prolonged strenuous exercsie, where intensity varies from point-to-point as in marathon running, it appears that factors other than carbohydrate energy substrate availability play an important role in mediating the strength of perceived exertion.

Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002 Nov; 34(11): pp1779-84

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.