You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Distance runners: should you be sprinting for performance?

SPB looks at new research on whether and how sprint-interval training could benefit middle and longer-distance runners when incorporated into real-world training programs

As all regular SPB readers will know, the topic of interval training and how athletes can maximize its benefits is something we’ve reported on extensively in recent years. In short, a very large body of evidence has accumulated over the past couple of decades showing that performing regular bouts of high-intensity interval training is an extremely effective training tool for athletes seeking to maximize performance for a relatively low training workload(1).

In plain English, short sessions of high-intensity intervals are a great way of producing gains in aerobic fitness, enabling athletes to sustain a higher intensity/pace/workload for longer before fatigue sets in. And as we’ve also discussed in previous SPB articles, high-intensity, short-duration intervals are also a very time-efficient for the fitness gains achieved, easy to add to an endurance program, and psychologically less demanding to carry out – all of which explain why they have become so popular.

The power of sprint intervals

Traditionally, interval sessions have typically been modelled around interval lengths lasting from 2-10 minutes, with intervals of 3-5 minutes becoming a popular and well-documented method for athletes and fitness enthusiasts seeking to improve aerobic fitness and endurance performance(2). The rationale for using 3-5 minute intervals is that there is a lag between starting a high-intensity effort and the cardiovascular system and muscles ‘catching up’ - a phenomenon that arises from the way the body responds to increase oxygen demand (more technically known as ‘oxygen kinetics’).

However, one of the key and more surprising findings to emerge from the more recent research on interval training is that very short, very high intensity intervals of 30 seconds or less duration can also be extremely effective for building fitness. This all stemmed from a landmark study by a Japanese professor called Izumi Tabata of the National Institute of Fitness and Sports in Kanoya, Japan(3).

In short, Tabata discovered that sessions consisting of a 4-minute period of eight very hard intervals (170% of VO2 max) with a 2:1 ratio between work and rest (ie 8 sets of 20 seconds of work followed by 10 seconds of rest) was as effective at building aerobic fitness as a 1-hour session of steady-state, moderate-intensity (70% of maximum oxygen uptake - VO2 max) endurance training. Subsequent research has validated that short and intense intervals are indeed an effective tool for developing fitness, even when the interval length is as short as 10 seconds, and especially where athletes need to also develop anaerobic power(4).

Sprint intervals for distance athletes?

There’s no doubting that high-intensity short (sprint) intervals are very time effective for developing aerobic fitness. But how relevant are these intervals for athletes performing over longer distances? The research here is rather unclear. A number of studies have suggested that endurance athletes can indeed significantly benefit from sprint type intervals. For example, studies show that multiple all-out sprints lasting no more than 40 seconds, with recovery periods five times longer than the sprint duration, can significantly improve the performance of endurance athletes(5). Additionally, training using all-out sprints of varying durations is known to be a key loading parameter for developing aerobic power(6). When using this approach, the most commonly used protocol involves performing 4 to 6 repetitions of 30-second all-out sprints, with a number of studies confirming the benefits for endurance athletes of this kind of interval session(7,8).

Question marks

Despite these findings however, there remain doubts and question marks. It was only last month that we reported on new research comparing equal workloads of long duration interval repeats consisting of 4 x 3-minute intervals with short-duration interval repeats consisting of 24 x 30-second intervals(9). Importantly, the intensities and total durations were matched between the two sessions. What emerged was that the time accumulated above 90% VO2max – a vital determinant of how effective a training session is for developing aerobic fitness - was significantly lower in the 30-second intervals compared to the 3-minute intervals (201.3 seconds in the short intervals vs. 327.9 seconds in the long), despite the intensity of the shorter intervals being higher than that of the longer intervals. Put simply, despite their lower intensity and same total interval work time, the long intervals were much more effective at generating oxygen uptakes above 90% VO2max. The ability (or lack of it) of short intense intervals to generate the high levels of oxygen uptake required for maximum development of aerobic power has also been questioned by other studies(10).

There’s also uncertainty due to the relative lack of research on other parameters of the short/intense interval protocol, such as repetition rate, training frequency, and training period – ie what combination works best for athletes. Moreover, most high-intensity/short interval studies have been conducted in controlled laboratory environments, typically using equipment such as power bicycles or treadmills, which don’t reflect the real-world demands of athletes engaged in competition, and which also make it difficult to conduct research on a large number of subjects (what’s needed to draw more robust conclusions). As a result, there is a dearth of field-based studies that have investigated the effectiveness of short/sprint interval training protocols with real athletes in their natural training environments.

New research

To try and understand the benefits or otherwise of sprint-interval type sessions in training for distance runners in real world conditions, a team of Chinese scientists has just carried out a study investigating the effects of 6-week sprint interval training compared to traditional training on the running performance of 5,000m distance runners(11). Published in the journal Frontiers in Physiology, this study compared the effects of a carefully designed sprint-interval training protocol with traditional endurance training methods on maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max), oxygen cost of submaximal running (a measure of running economy), time to exhaustion (TTE), and timed running performance for the 100m, 400m, and 3,000m distances.

What they did

Twenty male well-trained distance runners (VO2max of 67.4mL/kg/min) with an average personal best time for the 5,000m distance of 14 minutes 38 seconds were recruited for the study and were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

· An intervention group, which performed sprint interval training over the 6-week intervention.

· A control training group, which engaged in traditional long-distance training.

Both groups completed their respective training regimens twice a week for six weeks and assessments to determine VO2max, oxygen cost, time to exhaustion (TTE), and best running times over the 100m, 400m, and 3,000m distances were taken before and after the intervention.

The training programs

All the runners engaged in regular aerobic endurance training, consisting of moderate-intensity jogging for 40–60 min, four days a week with one day off per week. However, on the other two days per week, the training varied as follows:

Sprint interval training protocol – this consisted of two days per week of 10 x repeats of 30-second maximal sprint runs on the track, with a 3.5-min recovery period between sets. During the recovery periods, subjects’ heart rates were maintained below 70% of their maximum. The starting workload for the first set was determined based on each subject’s average workload from their 100m performances. Within each training session, the intensity was gradually reduced from interval to interval, as sustaining the high intensity of a 30-second maximal sprint is not feasible for 10 consecutive repeats. The average interval intensity during a training session was approximately 175% of the maximal aerobic speed. NB: MAS –is the maximum speed that can be sustained without a rapid accumulation of lactate, which then forces you to slow down.

Control training protocol – this consisted of two days per week of various traditional endurance training programs on the track based on established endurance training methods that focus on improving aerobic capacity through sustained, moderate-intensity exercise, including: 10km running, 2 x sets of 3000m, 3 x sets of 2000m, 4 x sets of 1500m, 5 x sets of 1000m, and 12 x sets of 400m(12). This protocol aimed to simulate a more traditional long-distance running approach commonly used by endurance athletes. The intensity of these sessions was prescribed based on a heart rate zone corresponding to 70%–85% of each subject’s maximum heart rate, which is typical for endurance training aimed at improving aerobic capacity.

What they found

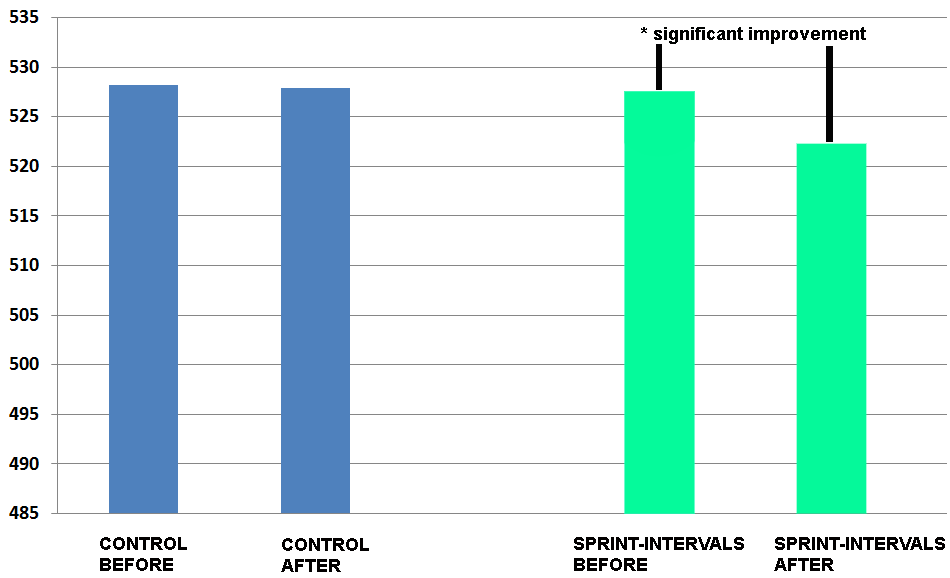

When the before/after measurements were analyzed, the data showed that the control (traditional) endurance training group made significant improvements in their 400m times. However, their gains were trumped by the sprint-interval training group; the runners showed significant improvements in time to exhaustion and running performance across both the 100m and 400m distances. Even more impressive is that the sprint-interval group improved significantly over the 3,000m distance, slashing an average of five seconds off their times compared with a non-significant 0.3 seconds improvement for the control runners (see figure 1). In their summary, the authors concluded that “sprint-interval training could be a practical addition to training programs” and that “coaches and athletes should incorporate two to three sessions of sprint intervals per week into their programs, focusing on high-intensity sprints followed by adequate recovery, as a way to complement traditional endurance training. This approach can enhance both aerobic and anaerobic capacity while reducing the overall training time required.”

Figure 1: 3,000m times before and after the intervention

Related Files

Practical implications

This new research provides further evidence that the use of repeats of 30-second sprint intervals (in this case, 10 x repeats performed twice per week) can significantly benefit the endurance performance of athletes in the real world, and may well be better than using traditional, longer-distance intervals such as 3 x 2,000m or 5 x 1,000m. It’s important to understand however that these were distance runners who were specialists at 5,000m, which straddles middle-distance and long-distance running events. Therefore, for 10km and above runners, we cannot be sure that performing intense sets of 10 x 30-second intervals, twice per week would yield the same benefits. Also, it should be emphasized that these sprint intervals were performed in combination with four days per week of longer-distance steady-state endurance training – not instead of.

How do these findings square with the findings that longer intervals rather than short sprint intervals are better for generating accumulated time spent above 90% of VO2max – a really important metric for improving maximum oxygen uptake, which is key for endurance performance? This may be because the runners were assessed over 3,000m, which requires a blend of aerobic and anaerobic power – as compared to events of 10km upwards, which rely much more on aerobic capacity. Had the running time trials been performed over 10km, the results may have been different. Another reason is that the faster sprint-type running performed in 30-second intervals is known to improve neuromuscular function and running economy more than long, slow distance running. That matters because running economy is another important factor that determines running performance over longer distances(13,14).

In summary then, we can conclude that for runners who are training for distances of 10km and under, the use of sessions of 30-second sprint intervals could be a good addition to your training program. However, if you’re new to sprint intervals, you will need to build into them gradually. For example, instead of performing two sessions per week, you can perform a single session per week and start with perhaps 6 x repeats rather than ten. Over time as you adapt, you can build to 10 x repeats per session and two sessions per week. To avoid the risk of overtraining and injury, it’s also important that you cut back on some of your steady-state training and ensure that you allow an easy or rest days after an interval day.

If you are a runner training for longer distances – eg 10 miles, half marathon etc – you may still benefit from some sprint interval sessions. However, given the differing demands of your event, just one session or sprint intervals per week may be more appropriate, supplemented with a second session of longer-duration intervals (something in the region of 2-5 minutes per interval). And of course, the same caution is required regarding injury and overtraining risk so build in gently!

References

1. Sports. 2015 Oct;45(10):1469-81

2. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Apr 2007;39(4):665-71

3. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997; Volume 29(3), pp 390-395

4. J Sports Sci Med. 2024 Dec 1;23(4):812–821

5. Scand. J. Med. Sci 2015. Sports 25 (Suppl. 4), 88–99

6. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022. 32 (5), 810–82

7. Sports Med 2017. 47 (12), 2443–2451

8. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 2017. 49 (6), 1147–1156

9. Front Sports Act Living. 2025 Jan 6:6:1507957

10. J Sports Sci Med. (2017) 16(2):219–29

11. Front Physiol. 2025 Feb 6:16:1536287. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1536287. eCollection 2025

12. Int. J. Sports Med 2022. 43 (4), 305–316

13. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991 Sep; 31(3):345-50

14. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006 Oct;31(5):530-40

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.