You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Plyometrics training: a little goes a long way for runners

How much plyometrics training is really needed to benefit running performance, and how frequently should it be performed? As Andrew Sheaff explains, new research suggests that less could be more…

Performance in running is a product of being able to produce a lot of energy and using that energy efficiently. In nutshell, successful runners are quite fit, and they’re able to run quickly without expending a lot of energy. A fast runner is the total package, possessing both of these qualities rather than just one or the other.

As a result, while performing run training only can produce results, it’s often insufficient to fully optimize performance, which is why resistance and plyometric training are becoming popular additions to runners’ training. These training methods are hypothesized to improve running economy by improving a runner’s ability to better manage gravitational forces, wasting less energy upon landing with each stride. However, while including exercises like plyometrics may make sense from a theoretical sense, our understanding of it use in practical terms is far from complete.

How much, how intense, how often?

Beyond questions of how to improve running economy using strategies such as plyometrics, more and more attention recently has focused on the question of training intensity distribution. Put simply, there are different strategies for how much time is spent running at different intensities during training, and some strategies may be more effective than others. Moreover, the benefits or otherwise of adding plyometrics into these different programs is far from certain.

Two popular intensity approaches are termed pyramidal training and polarized training. With pyramidal training, there is a large amount of low intensity training, a smaller, yet significant amount of threshold (moderate-high intensity) training, and a small amount of very high intensity training. In contrast, polarized training consists of very large amounts of low intensity training, small doses of threshold training, and slightly larger amounts of very high intensity training. It remains unclear how these training approaches impact performance, as well as how effective plyometric training is when incorporated with either strategy. But now new research has attempted to answer this question.

The study

To determine just how impactful a short-term plyometric intervention is, as well as how the intensity distribution of running training affects performance, a group of Italian researchers recruited runners to perform several different training interventions. Sixty well-trained runners, possessing an average V02max of 60 ml/kg/min, participated in the study. They were split into four separate groups that each trained for eight weeks:

- One group performed a polarized run training program.

- A second group performed the same run training with the addition of a plyometric training program.

- A third group performed a pyramidal run training program without plyometrics.

- A fourth group performed a pyramidal run training program but also added plyometrics.

Importantly, the run training was standardized so that the runners performed the same total load, even though the types of training were distributed differently.

The plyometric training element in those who included it was performed once per week, with a total of 60 jumps per session, performed as 6 sets of 10. Each jump was performed as a drop jump where the subjects stepped off a box and tried to jump as high as possible immediately after contacting the ground. Two sets were performed from a 20cm box, two sets were performed from a 40cm box, and two sets were performed from a 60cm box.

Testing

To determine the effectiveness of each of these interventions, the researchers implemented a battery of tests. As the researchers wanted a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the interventions, they conducted tests for power, metabolic fitness, and endurance performance. The subjects performed maximum squat jump and maximum counter-squat jumps. They were also tested for their running velocity at a blood lactate of 2mmol/L and 4mmol/L, as well as peak oxygen uptake. Finally, they performed a 5-kilometer time trial to assess the impact of the interventions on the most important variable of all, performance.

The findings

The results demonstrated a clear and positive impact of the plyometric training. For the pyramid and polarized groups that performed plyometrics, squat jump and counter-squat jump height improved significantly, whereas in the other two groups, they did not. Perhaps unsurprisingly, jump training improved jumping performance, even when performing strenuous running training at the same time.

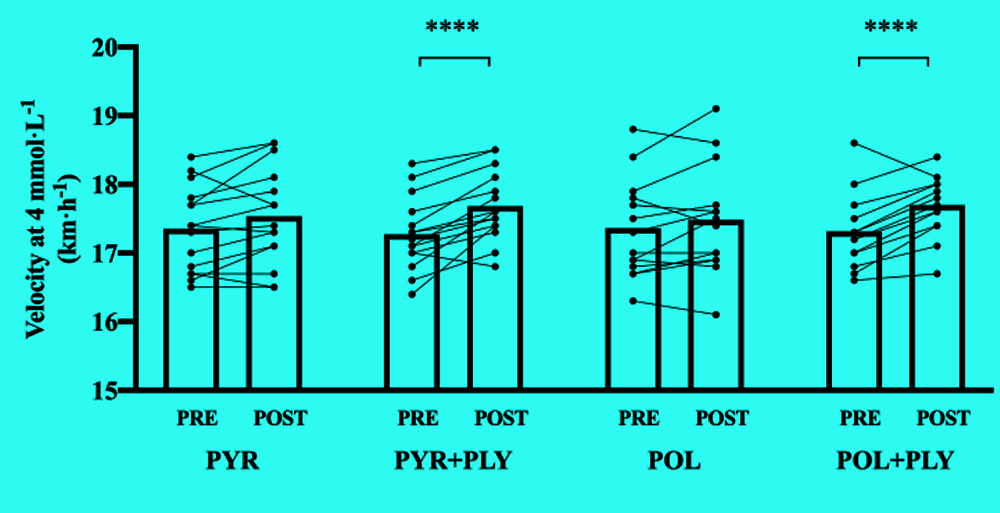

More interestingly, the positive impact of plyometric training was not limited to measures of power. Larger improvements in the running velocity at 2 and 4 mmol/L of blood lactate concentration were found in the plyometric training groups, even though all groups performed the same run training (see figure 1)! Interestingly, there were limited changes in peak oxygen consumption, implying that improvements may be due to more efficient running economy or lactate metabolism, rather than oxygen consumption. Finally, improvements in 5-km time trial were significantly greater in both the training groups that had included plyometrics.

Figure 1: Effect of plyometrics training on running velocity at 4mmol/L lactate threshold

Adding plyometrics training enabled the runners to maintain a faster pace at second lactate threshold (4mmol/L – the intensity above which fatigue very rapidly sets in) regardless of the running program they had followed. Individual dots and lines = plot for individual runners. Bars = average for the group. Note that while all training groups increased their pre/post performance, only the groups performing additional plyometrics increased performance significantly.

Overall, the addition of plyometric training, performed only once per week, improved markers of power, metabolic fitness, and performance. Interestingly, it appears that the intensity distribution of the running training was less important than the inclusion of plyometric training, as there were no differences between the polarized and pyramidal training programs. This is a powerful finding as it indicates that including high intensity, short duration training can not only improve power performance, it can improve endurance performance as well. This is particularly relevant as the subjects were already fit and well trained.

Getting practical

The biggest practical application of these findings is that all endurance runners should include plyometrics of some type in their training programs. One can implement the specific protocol used in this study, or a different protocol of similar design and intention. Including a plyometric program can dramatically improve markers of power, speed, and endurance.

In short, jump training positively influenced every aspect of performance of value to the endurance runner. Perhaps what’s so attractive about implementing this type of training is the minimal investment that it requires. Significant performance improvements were found when performing the training just once per week, for eight sessions in total. That’s a major return on a relatively small time investment!

Athletes can also rest assured that the plyometrics training can be integrated into almost any running program. In the study, very similar results were achieved regardless of whether the subjects performed a pyramidal or polarized training program. While running training has a positive impact on performance, it seems that the inclusion of plyometrics once per week has an additive impact on performance.

However, if you’ve never performed plyometrics training, and you’re looking to add it to an existing training program, you should exercise caution. While plyometric training is not necessarily physically exhausting, it can exert a significant strain on muscles, tendons, and bones (a strain which ultimately serves to improve performance). If the added loading is introduced too aggressively, the potential for injury exists. Bear in mind too that heavy resistance training is likely to be at least as effective, if not more so, in enhancing performance (see the article elsewhere in this issue, which perhaps makes it a better conditioning method for injury-prone runner. That said, plyometrics is quick and easy to perform, so athletes wishing to try it should be patient, increase the loading conservatively, and reap the benefits of this powerful training stimuli.

References

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022 Nov 3. doi: 10.1111/sms.14257. Online ahead of print.

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.