You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Running efficiency: stretching the truth

SPB looks at new research investigating the effect of flexibility on running efficiency, and whether a stretching program helps or hinders running performance

One of the most fundamental requirements for excellent running performance is an efficient running technique, where the amount of forward motion produced by the working muscles is maximized during submaximal workloads. More correctly known as ‘running economy’, runners with a high level of running economy can cover more ground at a given pace while using less oxygen per kilo of bodyweight than runners with poorer running economy. And since there’s a limit to the amount of oxygen that can be pumped around the body to working muscle before lactate accumulation starts to set in (producing fatigue and slowing the pace), runners with higher levels of economy will – all other things being equal – outperform runners with lower levels of economy.

Running economy is important

If muscle economy measures how efficiently muscles work at submaximal work rates (ie not flat out at maximum oxygen uptake), why is it important for maximising race performance? That’s because it turns out that a large body of evidence has found that elite athletes have much higher levels of muscle economy than their amateur or recreational counterparts. In other word – muscle economy and high levels of endurance go hand in hand. For example, a study of collegiate cross-country team members discovered that just two factors – maximum aerobic capacity (VO2max) and running economy - could account for 92% of the variance in performance during an 8000-metre race(1). Also, running economy, like VO2max, has successfully been used to estimate average marathon pace in elite runners(2).

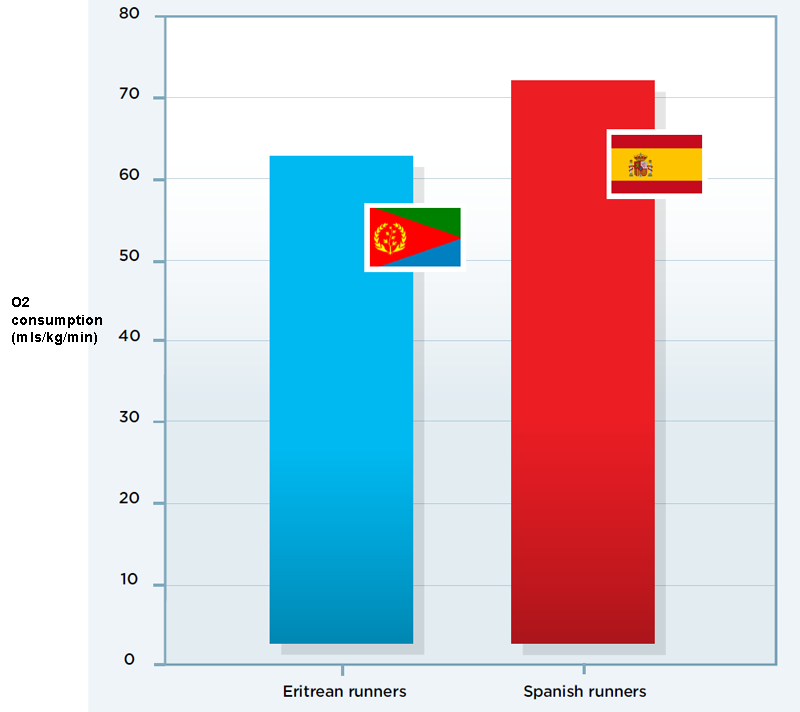

In another study, researchers were mystified as to why the performances of a group of elite Eritrean runners were consistently better than those of a group of elite Spanish runners, even though both groups had very similar maximum aerobic capacities(3). Subsequent testing on both groups revealed that the key physiological difference was the exceptional running economy of the African runners; at 21kmh (13.0mph), the Eritreans needed to consume just 65.9mls of oxygen per kilo per kilometre - compared with 74.8mls of oxygen for the Spanish runners (see figure 1)!

Figure 1: Figure 2: Oxygen consumption (mls/kg/min) at 21kmh

Improving running economy

Given the importance of economy for running performance, it’s not surprising that much research has been carried out into what affects economy and how to improve it. The data shows that when it comes to other modes of training that can boost running economy, both plyometrics training and resistance training are effective if carried out for a period of eight weeks or more(4,5). The most likely explanation is that when these training modes are performed frequently, the muscle-tendon unit becomes ‘stiffer’ and ‘springier’, which increases the amount of energy return (ie reduces energy loss) following each footstrike(6). There’s also evidence that regular massages can also help improve tissue function in the muscle-tendon unit, making it more elastic and improving running economy(7).

Another training mode that has been researched for its potential to improve running economy is stretching. The reasoning is that if stretching can increase the free range of motion of joints and reduce internal friction within muscle units, less energy is required to move the limbs through that range of motion, which should increase running economy(8). However, against this argument is that good running economy needs stiff and springy muscle tendon units (see this article); if stretching reduces muscle-tendon stiffness, it may actually harm running economy(9).

Stretching and running economy

When it comes to research on stretching and running economy, the data is mixed and complicated by the fact that a) runners use different types of stretching (ie static and/or dynamic) and b) these different stretching modes are often blended into a general pre-run warm-up routine, which is known to help boost economy when that warm up contains dynamic stretching(10). In a 2021 review study (a study that surveys the results of a large number of previous studies to draw more robust conclusions), researchers investigated the effects of a bout of pre-run stretching of different types on running economy and running performance in both recreational and elite athletes, as well as non-athletes(11).

To do this, a search for relevant studies investigating the effects of pre-exercise stretching on running economy plus other performance variables was conducted. In total, 11 studies containing 111 participants were identified and analyzed. The results were as follows:

· Regardless of the stretching technique, runners experienced both positive performance variables (eg oxygen uptake, time to exhaustion, total running distance) and negative performance variables (eg one mile uphill running time, ground contact time and 30-minute running performance when stretching was performed prior to running.

· Although it was observed that a single static stretching exercise with a duration of up to 90 seconds per muscle group led to small improvements in running economy (+1%), this came with negative effects on running performance.

· A single bout of dynamic stretching with an overall stretch duration (including all muscles) between 217 and 900 seconds resulted in a small negative change in running economy (-0.8%) but actually produced a large increase in running performance (9.8%).

· In general, only short static stretching durations of 60 seconds or less per muscle-tendon unit were considered advisable when performance needed to be maintained.

· Where pre-run stretching was performed on its own (ie without an additional warm-up), dynamic stretching for no more than four minutes produced the best performance gains.

· Less flexible runners seemed to experience greater benefits from stretching than athletes with normal flexibility, suggesting that less flexible runners could improve running economy by training for an optimum amount of flexibility.

Long-term stretching and economy

The research above summarized the findings on a single bout of pre-run stretching and running economy/performance. But what about the benefits or otherwise for a longer-term program of stretching on running economy? To answer this question, we can turn to brand new research conducted a by a team of US scientists, which was published just two weeks ago in the Journal of Sport Rehabilitation(12). In this study, the researchers set out to determine both the short-term and longer-term relationships between measures of static flexibility, and the subsequent impact on running economy.

Seventy-one healthy recreational runners (34 males and 37 females, age with an average age of 36.4 years were recruited to the study. Before the intervention began, all the runners completed an aerobic fitness assessment to determine their maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) and running economy. The economy assessment was a submaximal test during which the runners ran at their self-selected half-marathon race pace, while for VO2max, the researchers estimated maximum oxygen uptake by extrapolating upwards to a flat-out effort. In addition, the runners performed a standing toe-touch test to assess hamstring and lower-back flexibility, as well as a weight-bearing lunge test for leg strength assessment.

These tests were then repeated again 2-3 weeks later to verify whether the measures of flexibility had changed over that period, and if so, whether that change had had any impact on VO2max or running economy. In between the two visits, the runners simply continued their normal self-selected training and physical activity. The final stage of the study was to monitor the runners’ performances in terms of average half-marathon pace in a running event that took place shortly after the two assessment sessions, and to see whether that was correlated with flexibility or changes in flexibility.

What they found

The scientists performed a sophisticated statistical analysis of the data. In particular, they wanted to assess the relationship between flexibility and running economy across the 2-3 week time period, and whether any changes in flexibility were associated with changes in running economy or self-selected pace during the run that followed. The findings were as follows:

· There were no significant differences between the flexibility measurements and running economy or self selected running pace between assessments 1 and 2.

· There were no significant associations between running economy or self-selected running pace and the scores in the weight-bearing lunge test or standing toe-touch test.

· However, when the runners were stratified by age, there was a very significant interaction between age and weight-bearing lunge test score on running economy when the runners ran at their preferred pace. The older runners (over 45) with less flexibility showed better running economy but the situation for younger runners (under 30) was reversed – ie when they were less flexible, they showed worse levels of running economy and greater energy expenditure.

When summing up their findings, the researchers concluded that reduced flexibility in older runners seems to improve running economy compared to younger runners. They also recommended that coaches working with masters runners should be aware of the potential performance benefits of decreased ankle joint flexibility, but also that this potential benefit also carries a greater risk of calf and Achilles tendon injury in these runners.

Practical implications

How and when should runners stretch for flexibility – either prior to a run, or more generally as part of a conditioning program? Does it help running performance through improved running economy? When it comes to a pre-run stretch, there’s good evidence that if it is performed as part of a general warm-up, dynamic stretching really does help subsequent performance, especially if the runner is not particularly flexible to begin with. This performance increase comes despite a marginal drop in running economy. Conversely, pre-run static stretching seems to slightly improve running economy but comes with a performance penalty, and is therefore not recommended.

Why does dynamic stretching, which results in a slight drop in economy, produce better post-stretching running performance than static stretching, which slightly increases economy? This is most likely due to an interference effect, whereby static stretching prior to exercise impairs the maximum contractile ability and stiffness of muscle-tendon units(13), both of which are essential for propulsion. So while static stretching may also lower internal friction in joints and muscles leading to slightly better economy, this cannot compensate for the temporary functional impairment induced in muscle-tendon units.

As to the need for an overall stretching program, the most recent evidence is that when running economy and performance are paramount, older runners may actually benefit from NOT performing a stretching program and remaining stiffer! This seems particularly true when it comes to the muscles and tendons of the lower leg – ie the calf muscle and Achilles tendon). In this study, the researchers were baffled as to why that could be the case.

One reason may be due to age-related changes in these muscles – for example muscle mass loss. As anyone who understands the physics of springs will know, a weaker spring exerts less restorative force. In older runners therefore, encouraging and maximizing the muscle-tendon stiffness of the lower leg by not stretching might help to compensate for this natural loss of muscle mass and ‘weakening’ of the spring system. Younger runners on the other hand are not so subject to this effect and tend to be naturally more flexible, which might explain why this observation (of being stiffer helping running economy) was not seen. Either way, more research is needed!

Of course, set against the potential economy and performance gains that older runners might experience by not attempting to increase flexibility is the potential for injury. Muscle and tendons that are very stiff are naturally more prone to injury because it’s the ability of these tissues to lengthen that helps absorb and spread the forces encountered more evenly. As any runner who’s encountered an Achilles injury will tell you, the recovery process is a slow one, which means a lot of time off training, leading to an inevitable decline in performance. Therefore, older runners who start to feel stiffness and tightness in the calf/Achilles area are probably better off performing a little bit of regular stretching to develop flexibility, especially if this stiffness is accompanied by niggling aches and pains!

References

1. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(12):2089–2097

2. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(10):1734–1740

3. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89(1):95–99

4. Sports Med 2017. 47 545–554

5. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 2007. 39 1801–1810

6. Physiol Rep. 2021 Oct;9(20):e15076

7. J. Sports Sci. Med 2020. 19 690–694

8. J Strength Cond Res. 2019 Jul;33(7):1921-1928

9. Sports Med 2015. Open 1 1–15

10. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2024 Nov 28;20(1):99-108

11. Front Physiol. 2021 Jan 20;11:630282

12. J Sport Rehabil. 2025 Feb 20:1-6. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2024-0312. Online ahead of print

13. J Sports Sci Med. 2023 Sep 1;22(3):465-475

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.