Athletes and nutrition: the unpalatable truth about daily diet

SPB looks at new research on the diets of elite swimmers, and explains why and how all athletes need to attend to dietary basics!

Many moons ago, I used to regularly give nutrition advice to athletes and gym users at my workplace. Despite having a good nutritional background under my belt and an in-depth understanding of the biochemistry underpinning the principles of nutrition, I soon discovered that translating this knowledge into positive results with clients was fraught with difficulty. The main reasons for this were that a) what clients thought they ate and what they actually ate were very different, and b) dietary practices that had been ingrained over years or decades were extremely difficult to modify; the client’s emotional and social connections to food and diet often trumped their desire to make positive changes.

Elite athletes and dietary basics

While the athletes I dealt with were very keen to improve their day-to-day diet, they were almost exclusively amateur athletes. Therefore, you might expect that when it comes to professional or elite athletes, the drive to attain the highest performance levels makes it much more likely that their dietary basics are excellent. This is especially the case given that many pro athletes have their own personal coaches and nutritionists - and even more so when you consider that in 2025, nearly everybody has 24/7 access to the internet and that there are numerous online software programs to help design well-balanced, nutritionally complete menus, which are readily available for mere pennies or even for free.

However, as regular SPB readers will know, this is sadly not the case. When we first reported on this topic for SPB back in 2010, we looked at data showing that elite and professional sportsmen and women across a wide range of sports and nationalities were saddled with poor nutritional habits, and we have also reported on more recent data confirming that many athletes are still not attending properly to the basics. Just a few examples of these findings include:

· Elite male swimmers – over 50% of whom were deficient in calcium and insufficient in carbohydrate intake(1).

· Female judo athletes who failed to meet their needs for iron, calcium B1 and niacin intakes(2).

· Female handball, runner, karate and basketball athletes, 100% of whom failed to meet their magnesium and copper intake requirements(3).

· Highly trained female cyclists, whose average daily intakes for folic acid, magnesium, iron, and zinc were sub optimum, while. More than one-third of the cyclists failed to consume even 60% of the recommended daily intake for vitamins B6, B12, E and the minerals magnesium, iron, and zinc(4).

· Seventy two elite female athletes where 65% failed to meet carbohydrate intake recommendations and many failed to meet their needs for for folic acid, calcium, magnesium, and iron(5).

· Over 550 Dutch elite and sub-elite athletes, the majority of whom had sub-optimum vitamin D intakes and where iron intake was sub optimum in a substantial number of the women(6).

· A study on collegiate distance runners, where the majority (73%) consumed less than recommended levels of carbohydrates while 50% of women and 24% of men did not meet the recommended daily allowance for calcium, and 95% of the runners did not meet the RDA for vitamin D(7)!

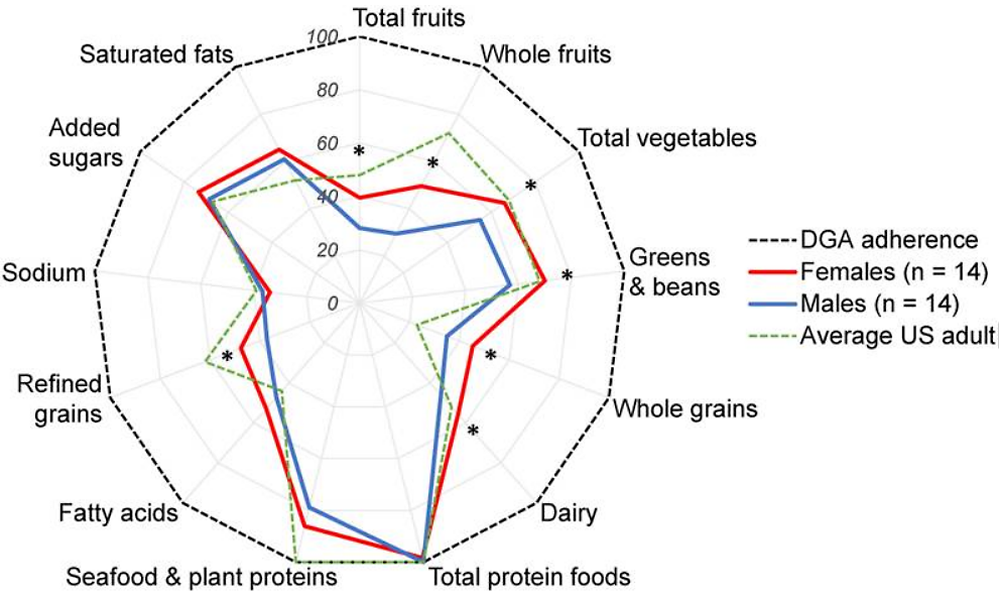

· A study on female and male NCAA Division I cross country student-athletes, which found carbohydrate intakes were below athlete guidelines in 43% of females and 29% of males, none of the 28 athletes met the RDA for vitamin D, only 79% of females and 36% of males met the RDA for calcium and where nearly all failed to meet the ‘Healthy Eating Index’ (HEI) guidelines for the main food groups (except protein foods) – see figure 1(8).

Figure 1: Athletes’ Healthy Eating Index scores for the main food groups

Getting the basics right

In the examples above of athletes failing to meet their nutritional needs, many studies found shortfalls in micronutrient intakes – for example sub-optimum levels of zinc, iron, calcium, magnesium, B vitamins and vitamin D. Perhaps this is understandable since information about the micronutrient content of most food products is not listed on the labels, making it harder to assess daily intakes without the use of additional aids such as nutrition software. When it comes to the macronutrients however – ie fat, protein, carbohydrate and fiber – labelling information makes it very easy for athletes (and anyone else for that matter) to keep track of daily intakes, and adjust these for optimum fuelling. And that’s a good thing because the optimizing macronutrient intake is absolutely essential for athletes seeking to maximize performance.

Carbohydrate, which serves as the primary energy source during intense exercise, is critical for maintaining muscle glycogen stores and providing readily available fuel during exercise(9-11). Protein meanwhile is essential for muscle repair and growth, and also aids in recovery and adaptation to training stress(12). Fat intake contributes to energy production during low-to-moderate intensity exercise, and plays a role in overall health by providing the body with essential omega-3 fatty acids, assisting with nutrient absorption, and supporting the immune system and hormonal balance(13).

If athletes are to ensure that the day-to-day diet meets their training and performance needs, getting the basics of macronutrient intake right is absolutely essential. However, in the study published last year on male and female NCAA Division I cross country student-athletes(14), this was most definitely NOT the case, with almost a half of female and a third of male athletes failing to consume enough carbohydrate, and nearly all failing to meet the HEI guidelines for the main food groups. This might seem very surprising but now, brand new research suggests that not adequately covering the basic dietary needs of macronutrient intake is not just limited to runners!

New research

Published just a few days ago in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, this study set out to assess the dietary and macronutrient intake of elite male and female swimmers(15). In addition to comparing the actual intakes of fat, protein and carbohydrate to that recommended in the US dietary allowance (USDA) guidelines and those recommended by the Internal Olympic Committee (IOC), the researchers also looked at the timing of macronutrient intakes (particularly during and following periods of intense/prolonged training, when in-exercise and post-exercise nutrition is vital for performance and recovery) and whether there were differences between the dietary habits of male and female swimmers.

What they did

Twenty-seven members of a NCAA Division 1 Swim team in the United States were recruited for the study; 11 males and 16 females. All swimmers were NCAA competitors, and some were Olympic Trials competitors also. Following measurements on body mass and composition, the swimmers were tracked for their daily dietary intake and energy expenditure (training and non-training) over a 6-week period, which constituted the heaviest training phase in the season, consisting of preparation for competition.

Energy expended

Energy expended (ie calories burned) during the swimmers’ in-pool training and resistance training sessions, and timing of expenditure bouts was measured directly using the a combination of ‘WHOOP heart rate’ and ‘3D-accelerometry analysis’ – a measurement technique that has been validated in previous research(16). Data collection occurred during the weekly training routines, which consisted of three resistance training sessions, six in-water sessions, and one recovery session. Training sessions during the week included: 2-hour in-water training sessions, and 1-hour resistance training sessions. Each week, swimmers averaged 38,850 yards (6,700 yards per training day), and trained approximately 18 hours. The total daily energy expenditure was comprised of the sum of energy expenditure during training plus non-training energy expenditure.

Energy intake

Total daily energy intake was assessed continuously from 3-day diet logs utilizing premium mobile applications such as MyFitnessPal, an app that has been validated for energy and macronutrient intake in the general population(17). The swimmers received training on how to use the mobile application for recording, how to scan labels of purchased food and drink as an entry for record and were provided information for estimation of portion sizes for foods that were individually prepared by themselves. The swimmers recorded all food, beverages, or calorie-containing items consumed over two weekdays and one weekend day. Dietary data also included the time of day, and meal type (meal or snack), item, brand and method of preparation.

Energy timing

In addition to the total day-to-day energy balance (intake vs. expenditure), the researchers also looked at the timing of macronutrient intakes through the day. In particular, the swimmers’ average hourly macronutrient consumption (grams per hour and grams per kilo) was analyzed to see whether and how it varied during or after training sessions. This was particularly focussed on carbohydrate intake, where in-training and post-training carbohydrate fuelling play a vital role in performance and recovery, allowing high-quality training sessions to take place day after day.

What they found

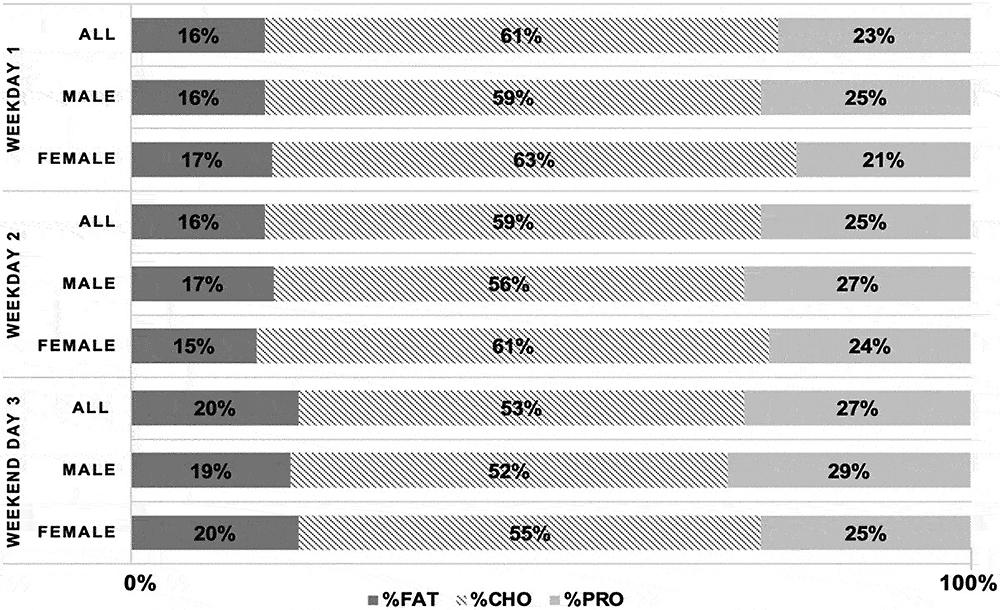

Twenty five of the 27 swimmers completed the study and when the data was analyzed, the researchers found that the swimmers averaged a calorie (kcal) intake of 2,940 per day. The macronutrient breakdown of this calorie intake was 57.0% carbohydrate, 17.0% fat and 26.0% protein (see figure 2, which depicts a visualization of the daily dietary composition and macronutrient distribution across the observation period for all male and female swimmers). The male swimmers had a significantly greater intake of all the macronutrients, both in total grams and in grams/kg of bodyweight/day (carbohydrate: 5.3 vs. 4.3g/kg/d for males vs. females; fat: 1.6 vs. 1.2g/kg/d males vs. females; protein: 2.6 vs. 1.7g/kg/day males vs. females).Compared to the recommendations for the general population, the swimmers did well; 25/25 (100%) swimmers met both the carbohydrate and protein recommendations.

However, when the swimmers’ diets were compared to the USDA and IOC athlete-specific recommendations, while 24/25 swimmers (96%) met the protein intake recommendations, only 7/25 swimmers (28%) consumed sufficient carbohydrate and only 6/25 swimmers (24%) met the fat intake recommendations. Breaking the findings down with regarding to timing of macronutrient intake, the results were equally concerning. None of the swimmers met the carbohydrate intake recommendations pre- or during exercise for the first training session of the day. And only 3/25 swimmers (12%) met the carbohydrate intake recommendations for post-exercise recovery after that first session. For the second training session of the day, 13/25 (52%) met pre-exercise CHO recommendations, while 6/25 (24%) and 11/25 (28%) met the ‘during’ and ‘post-exercise’ recommendations respectively.

Figure 2: Daily distribution of macronutrient intake of all swimmers

In their summing up, the researchers stated that “while the majority of swimmers met protein intake recommendations, deficits in fat and carbohydrate intake, especially around training sessions, highlight the ongoing need for tailored nutritional interventions” and that “addressing these gaps is crucial for optimizing fuelling strategies, enhancing endurance performance, promoting proper recovery, and maximizing training adaptations among endurance athletes”.

Practical implications for endurance athletes

The above study highlights yet again how even elite athletes are often failing to get the dietary basics right. In this case, both the amount of carbohydrate consumed and its timing were not sufficient to meet the optimum needs of the swimmers during periods of hard training. As the years tick by, high-quality nutritional knowledge becomes ever more accessible yet it seems that the basic nutritional practices of athletes are not significantly improving. Why is this so? A possible explanation is that many athletes are seduced by ‘hi-tech’ nutrition, assuming that so long as they consume advanced protein and carbohydrate powders, the nutritional content of their meals every day is less important. There’s also the issue of time and convenience. Many time-pressured athletes remain unaware that spending time in the kitchen preparing high-quality meals is a vital part of the training and recovery process. Simply grabbing snacks and topping up with sports drinks is no substitute! The obvious way forward is to help athletes understand why dietary basics are so incredibly important for performance, and how they can optimize their diet with simple but long-term dietary changes. This can be done by either self education or by athlete coaches.

For younger athletes competing at a high level, the coach is probably in the best position to help athletes understand and improve their diet. However, most of you reading this will be older and self coached; if you are still not sure about how to get the dietary basics right and not rely too heavily on sports nutrition products, there are a couple of excellent articles worth reading. The first is this article, which explains the common dietary mistakes athletes make, and directs athletes on how to get professional help to kick start the process. Alternatively, this article looks at nutrition hierarchy, explaining how you can ensure you’re focussing on the right elements of your diet, explaining when and how sports nutrition products may be used to complement a diet that’s intrinsically nutritious and well balanced! Finally, it may be worth investing in a good nutrition/fitness app such as MyFitnessPal, which can help simplify the process to monitoring the content of your day-to-day diet, especially when features like label scanning are used.

References

1. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004 Feb;14(1):81-94

2. Nutrition. 2002 Jan;18(1):86-90

3. Int J Sport Nutr. 1999 Sep;9(3):295-309

4. Am Diet Assoc. 1989 Nov;89(11):1620-3

5. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010 Jun;20(3):245-56

6. Nutrients. 2017 Feb 15;9(2). pii: E142. doi: 10.3390/nu9020142

7. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020;39(8):747–755

8. Curr Dev Nutr. 2024 Oct 15;8(11):104475

9. Acta Physiol Scand. 1967;71(2):140–150

10. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(7):675–685

11. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(1):126–134

12. Front Nutr. 2018;5:83. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00083

13. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(7 Suppl):S389–95

14. Curr Dev Nutr. 2024 Oct 15;8(11):104475

15. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2025 Dec;22(1):2494846. Epub 2025 Apr 18

16. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2023;48(1):74–87

17. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e18237

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.