You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Endurance nutrition: go with your gut feeling

Which are the best nutritional strategies to avoid gut problems during that all-important race or training session? SPB looks at some new research that sorts the wheat from the chaff

I still remember that frosty January day in 1987 clearly. While preparing for a forthcoming marathon, I set off on my Sunday morning long run aiming to complete a new 16-mile route. However, it was just three miles in when I was hit by a nagging gut pain that steadily worsened and became excruciating. I was forced to slow to a slow jog but that wasn’t the worst of it; after the gut pain came the uncontrollable urge to run to the loo. It was all I could do to abandon the run and try to get back home via various loo stops along the way, hoping not to completely humiliate myself. I made it (just) but it was a lesson to me: if you want to ensure a good athletic performance, never ignore your gut and take great care of what you eat before an important event or training session!

Gastrointestinal distress and the athlete

The episode above was an extreme example of gastrointestinal (GI) distress, and luckily for me, was something that wasn’t a regular occurrence. However, many athletes, even when avoiding obvious dietary pitfalls (for example, consuming a large amount of dried fruit the day before!), struggle with GI distress on a regular basis, either when training or during competition. Data from studies on this topic shows that least 30 to 50 % of endurance athletes experience GI symptoms during exercise on a regular basis(1).

Research also shows that of all athletes, long-distance runners are particularly prone to GI distress, with between 30% and 90% experiencing symptoms on an occasional or regular basis(2,3). Regarding GI distress symptoms, these are often classified according to the anatomical origin. Thus GI symptoms can be classified into upper-GI symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, stomach pain, belching etc), and lower-GI symptoms (flatulence, lower abdominal bloating, urge to defecate, intestinal pain, diarrhea, etc.). In addition, other symptoms can occur that are GI-related but don’t fit into the upper-and lower-GI categories – eg nausea, dizziness, acute transient abdominal pain(4).

Causes of GI distress

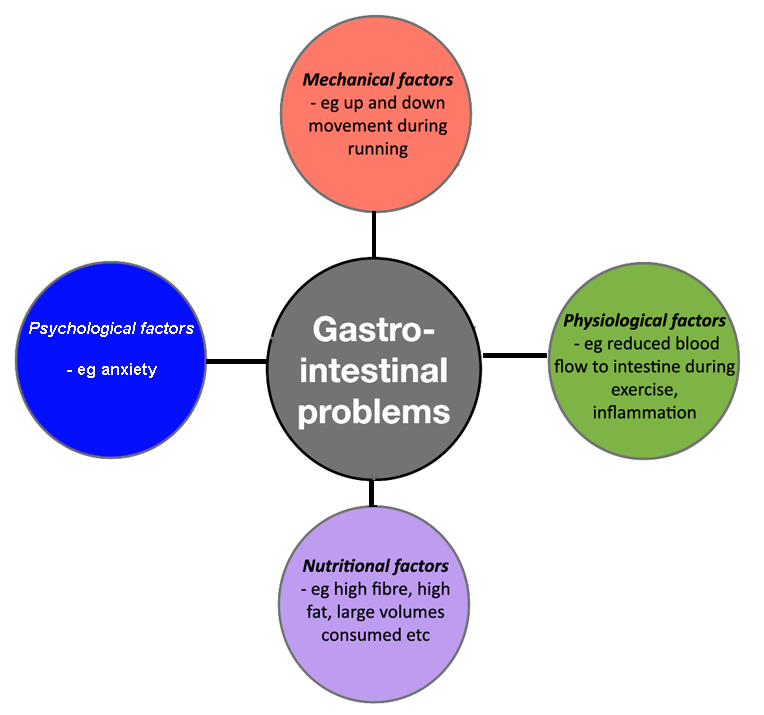

Past research has recognized four main causes of GI symptoms in runners (see figure 1):

· Physiological causes - due to a phenomenon known as splanchnic hypoperfusion (see box 1 and this article), a process where blood flow is diverted away from the gut and towards muscles during exercise, reducing the ability of the gut to function efficiently(5).

· Mechanical causes - related mostly to how force acts on the GI tract during the impacts generated during foot strike, but also related to the influence of changing posture during exercise(6).

· Psychological causes - where different psychological states are thought to be connected with higher occurrence rates of GI symptoms via the gut-brain axis(7).

· Nutritional causes – which we will be focusing on in this article(8).

Box 1: What is splanchnic hypoperfusion?

Splanchnic hypoperfusion is a condition where the normal patterns of blood flow to the intestines and organs in the abdominal region are disturbed for example during vigorous exercise, when blood is directed away from the abdominal region to supply the working muscles with more blood (and oxygen).

When SH occurs, the result is micro-trauma/injury to the small intestine, which then causes the gut to become ‘leaky’. This in turn results in a range of gastrointestinal symptoms such as cramps and nausea, which can severely dent athletic performance. The good news is that research suggests the amino acid citrulline can help preserve blood flow to the small intestine, which could help reduce the incidence of SH in athletes.

Figure 1: The four factors involved in generating GI distress

Nutrition and GI distress

Of these four factors contributing to GI distress, athlete nutrition has attracted the most attention. This is because not only does nutrition have a large impact on the gut (for obvious reasons), but it’s also the most modifiable. Previous research on nutrition and GI distress has looked at a number of aspects that might affect GI health – either in a negative or positive way. For example, in endurance athletes consuming carbohydrate on the move (ie drinks, gels and bars), studies have investigated how carbohydrate type, concentration and osmolality (a measure of the number of particles in a given volume of fluid that are able to undergo osmosis and cross biological membranes) and the impact on the incidence of GI distress. More generally, the role of day-to-day diet in terms of intakes of fiber, protein, and fat has also been investigated.

More recently, there’s been a lot of interest in ‘high-FODMAP’ foods and the role they can play in generating GI distress. The acronym FODMAP stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides MonosAccharides and Polyols. All of these foods are carbohydrates, which are high in certain natural sugars such as fructans, galacto-oligosaccharides, sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, xylitol and isomaltose. The important thing to understand is that high FODMAP foods increase osmotic load in the gut and colonic gas production, which may exacerbate symptoms in sensitive individuals(9). Consequently, a low-FODMAP diet has gained attention as a potential strategy to reduce GI distress, especially as this kind of diet can also help manage irritable bowel syndrome symptoms (IBS)(10).

Another strategy to relieve GI distress that has come under the spotlight recently is one of using probiotics (healthy bacteria) supplements to change the gut microbiota composition in a way that favours better gut health. Studies have therefore investigated if, and which kinds of probiotics can reduce GI distress symptom severity and occurrence in athletes(11). Yet another strategy that has been investigated recently is the use of hydrogel-based carbohydrate products for consumption on the move. The theory is that these kinds of energy products can encapsulate CHO in the stomach and reduce fermentation, which may in turn reduce the severity of GI symptoms while boosting CHO availability during exercise (see this article on hydrogels).

Choosing the best strategy

If you’re an athlete who struggles with GI distress during training or competition, you might be wondering which of the above nutritional strategies is the most effective for reducing symptoms? The good news is that a team of Slovenian and German scientists have tried to answer this very question in a new study(12). Published in the ‘Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition’, this study consisted of a systematic review of all the previous literature on nutrition and GI-distress in athletes in order to come up with some best-practice recommendations.

To do this, the researchers searched the scientific databases for any studies that had been carried out previously on the topic of GI distress and exercise and/or athletic performance. They then sought to analyze and combine these study findings to come up with ‘best-practice’ recommendations. The criteria for inclusion of the previous studies for analysis were as follows:

· Contained accurate information regarding the type and intensity of exercise during study.

· Provided a detailed explanation of planned nutritional intervention, including dose/exposure.

· Provided relevant details regarding reporting of GI symptoms along with statistical data.

· Reported the details of participants included in the study.

Overall, 29 studies on nutrition and GI distress in athletes met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review, the details of which can be found in table 1 of the review. The data from these studies was then synthesized and combined to draw robust conclusions. To add clarity to the findings, the findings were categorized into five distinct areas of research: gut training protocols, effects of different carbohydrate solutions and mixtures, low FODMAP diets, hydrogel CHO technology, and probiotic supplementation.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

*Gut training protocols to reduce GI symptoms while consuming carbohydrate drinks and gels on the move showed promising results. Two weeks of purposeful repetitive intake of carbohydrate during running lowered the severity of GI symptoms and resulted in a lowered malabsorption of carbohydrate. Likewise, repetitive running sessions with an intentional ingestion of a higher volume of liquid during running produced a gradual improvement in tolerating fluid intake during running, and a reduction of GI symptoms. In short, the GI tract seems able to adapt to ingestion of higher amounts of CHO and a higher volume of liquid during exercise in a relatively short period of time, making a good practical strategy for runners seeking less GI distress.

*Correct dosing and type when using carbohydrate on the move was another important factor in minimizing GI distress. In particular, carbohydrate bars caused more GI distress than drinks or gels, most likely because the small amounts of fat and protein present delay gastric emptying. Concentration also plays a role, with (more concentrated) gels more likely to cause GI distress than drinks. For drinks, a concentration of around 6% (60 grams per litre) seemed to be optimal in terms of minimizing GI distress. For any given concentration, glucose-fructose mixtures were better tolerated than pure glucose. The optimum ratio seems to be around 1.2 grams to glucose to 1.0 gram of fructose – ie a 1.2 to 1 ratio. This ratio enabled a consumption rate of 78 grams per hour with minimal GI distress.

*Low FODMAP diets seemed to be beneficial overall, despite the fact that there is a relative lack of research into these diets and exercise-related GI symptoms. All the studies to date have showed an improvement in either incidence or severity or both of GI symptoms when there is a reduction of FODMAP in the diet – usually within 24 hours. However, caution is required when using these diets as athletes may run the risk of consuming a carbohydrate-deficient diet, with negative performance consequences, which could offset any benefits. Because of this, short-term implementation of a low-FODMAP diet may be a better choice for endurance athletes than multi-day long-term protocols – for example, restricting the use of a low FODMAP diet to just before competitions or only on intensive training days.

*Hydrogel carbohydrate products (contrary to marketing hype) have so far failed on balance to demonstrate any significant benefits - either for improving GI symptoms or for enhancing exercise performance. In fact, the only observed advantage of consuming carbohydrate hydrogels has been shown in just one study when ingesting larger than the maximum recommended carbohydrate intake on the move (90 grams/hour), and in long-duration, high-intensity sessions. However, the available research on these products is still quite limited; while they cannot currently be recommended as method of reducing GI distress, there may be some limited circumstances in which they offer benefits over and above high-quality glucose-fructose drinks.

*Probiotic supplementation study findings are somewhat mixed, with some studies showing a significant reduction in GI symptoms after probiotic supplementation, but others finding no benefits. Overall, there research to date shows a small potential to reduce the incidence and severity of GI symptoms, probably through maintaining intestinal integrity and perhaps improving immune function. These conflicting findings may be as a result of the many different probiotic strains used in the studies, and the fact that it can take many weeks or even months of probiotic use to change the gut biome for the better. While there may be some GI distress benefits (and for athlete health in general), more research is needed before we can recommend probiotic supplementation as ‘go-to’ option for athletes who struggle with these symptoms.

Summary and recommendations

The onset of GI distress symptoms is very complex phenomenon, and that onset is influenced by a huge variety of factors. Therefore, the elimination (or at least reduction) of GI symptoms during exercise must be approached very individually and thoughtfully. In plain English, what works for you might not work for another athlete and vice-versa! Having said that, gut training protocols that involve ‘training the gut’ by the regular consumption of carbohydrate and fluids during endurance workouts, show great promise in enhancing nutrient absorption and reducing GI discomfort over time. In addition, using mixed carbohydrates such as glucose-fructose drinks is more effective in minimizing GI symptoms compared to single carbohydrate (eg glucose only), especially at high intake levels, and drinks tend to fare better than gels, while both fare better than bars

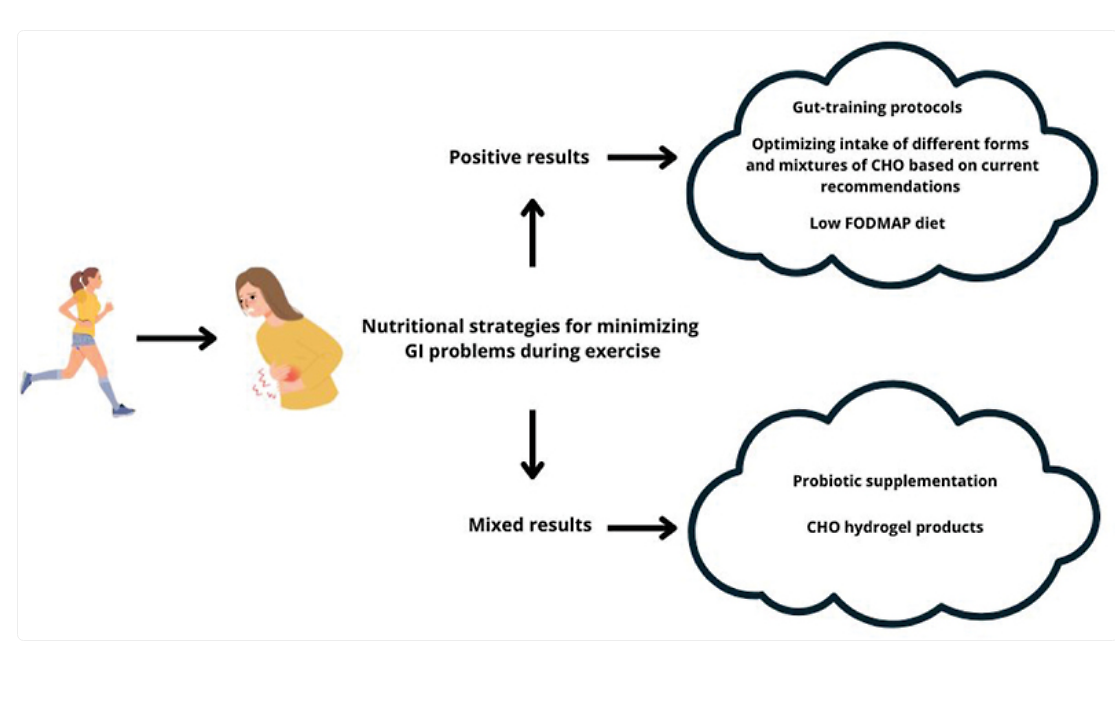

A low FODMAP diet also shows potential to reduce GI symptoms but it requires careful implementation to avoid negative consequences such as reduced energy intake. A preferred way of implementing a low-FODMAP diet therefore is to reserve it for actual race days and key training sessions rather than using it on a day-to-day basis. Even better is to identify and exclude specific nutrients from the FODMAP group that may be causing your symptoms. The evidence for probiotic supplementation is fairly mixed, so this should be considered as an additional rather than a core strategy for reducing GI distress (although probiotics are known to boost health and immunity). Finally, while there’s a lot of marketing hype (and extra cost involved!), the evidence for hydrogel use in carbohydrate supplementation is weak so these products cannot be recommended based on our current knowledge. Figure 2 sums up these recommendations.

Figure 2: Recommendations to reduce GI distress in endurance athletes

Related Files

References

1. Sports Med. 2014;44(S1):79–85

2. Sports Med. 2017;47:101–110

3. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1570–1581

4. Sports Med. 2014;44(S1):79–85

5. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303(2):G155–G168

6. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(5):533–538

7. J Sports Sci. 2018;36:1713–1719

8. Int J Sport Nutr. 1992;2(1):48–59

9. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(1):116–123

10. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0182942

11. Nutrition. 2019;60:152–160

12. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2025 Dec;22(1):2529910. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2025.2529910. Epub 2025 Jul 11

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.