You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Older athletes: is ginger the spice of life?

SPB looks at new research on ginger and inflammation. Can it really help older athletes combat joint pain and stiffness?

For athletes, inflammation is something of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, a degree of inflammation post exercise is a natural and healthy response to a training load imposed on the muscle. That because we now known that inflammation plays an integral role in the training adaptation response(1); not only is inflammation required as part of the process where damaged muscle tissue is broken down and then repaired, but it also acts an adaptation signal, helping to switch on key genes involved in the process of muscle synthesis and aerobic adaptation – a process that research shows is suppressed when anti-inflammatory medication is taken(2). Inflammation is also part of the natural healing process following an injury.

However, despite the critical role that inflammation plays in the process of muscle growth and training adaptation, there is a big downside, especially when inflammation becomes excessive or chronic. While some inflammation is a part of the natural healing/adaptation process and a desirable thing, chronic or excessive inflammation is not. When inflammation becomes chronic – something that becomes more common as we age - it can result in damage to healthy tissue, which triggers further inflammation, leading to a vicious circle(3). This age-related increase in inflammation partly explains why older athletes often suffer from more post-exercise soreness for longer following a harder or longer training session. It also helps explain chronic aches and pains in the joints and muscles that may be present even in the rested condition.

Chronic inflammation is also linked to diet; a very recent study found that in older people, the higher the proportion of ultra-processed foods – ie rich in refined grains, sugars and processed seed oils - consumed in the diet, the greater the levels of inflammation were present, and the poorer the levels of strength and agility(4). The dietary link to chronic inflammation also operates in the reverse direction; for example, a Mediterranean-type diet is known to reduce chronic inflammation(5) and likewise, diets rich in the essential fat omega-3 have also been documented to reduce inflammation(6).

Fighting inflammation

For older athletes seeking to maintain training volumes and performance, the presence of inflammation-related aches and pains presents a real challenge. When inflammation becomes chronic and begins to affect joints and range of movement, many athletes understandably reach for anti-inflammatory medications in the form of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Ibuprofen, aspirin etc. And when inflammation flares up, many physicians will prescribe stronger NSAID medications such as Naproxen.

However, while effective in the short term, the long-term use of NSAIDs carries the risk of damage to the lining of the stomach, leading to stomach ulcers and gastric bleeding, which can be potentially very hazardous(7). To make matters worse, even the short-term use of NSAIDs may be undesirable because indicates that NSAIDs can delay muscle regeneration and training adaptations(8). More than that, NSAID use may reduce ligament, tendon, and cartilage healing following injury, making a re-injury or chronic injury more likely(9,10).

A more natural approach

In a previous SPB article, we investigated research on more natural and safer options for combating chronic or excessive inflammation. In it, we highlighted research suggesting that a number of naturally occurring food compounds such as curcumin from turmeric and tart cherry extract can help counter inflammation - without the undesirable side effects of medication. Indeed, some of these extracts may also enhance recovery and performance in their own right, and confer additional health benefits such as a reduced risk of degenerative diseases like coronary heart disease and cancer.

In recent years, there’s been a huge interest in these natural anti-inflammatory nutrients and their health benefits, particularly for curcumin. However, there’s another nutrient that has increasingly begun to attract attention for its anti-inflammatory effects and that’s ginger. Ginger is not an exotic nutrient/food extract and most of us have probably consumed products containing ginger, perhaps even quite frequently. However, don’t let its lowly status fool you; ginger has some remarkable properties.

The magic of ginger

Ginger (full botanical name Zingiber officinale Roscoe – see figure 1) is a flowering plant found primarily in Southeast Asia that has been utilized as a spice and in ayurvedic medicinal practices. Ginger can be consumed in a variety of ways – either whole root (eg in cooked food recipes), in ginger extract powders, and as a herbal tea(11). Traditionally, and especially in Eastern medicine, ginger has been used to help resolve various ailments, including colds, nausea, fevers, headache, and gastrointestinal issues(12). However, ginger is also able to modulate inflammation due to its pharmacological activity – most notably through the anti-inflammatory effects of its phenolic compounds, which include gingerols, shogaols, paradols, and zingerone(13-15).

Figure 1: Ginger root

Of these phenolic compounds, gingerols are the most studied in terms of anti-inflammatory effects (although there’s also much interest in how gingerols also exert antioxidant and anticancer effects)(16-18). When ginger is consumed as raw product, gingerols are the primary polyphenols found within the ginger root. However, when ginger is heated, gingerols can be converted into shogaols, paradols, and zingerone due to slight alterations in the molecular structures of these compounds. These compounds also exert anti-inflammatory effects albeit via slightly different biochemical pathways(19).

In terms of clinical studies, several animal studies have shown that dried ginger or ginger extract can reduce acute inflammation, while in humans, several clinical studies support the value of ginger for the treatment of osteoarthritis, and in some cases, a significant reduction in knee pain has reported(20-22). Some of these trials also found that ginger relieved pain and swelling to varying degrees in patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and muscular pain - without causing serious adverse effects even after long periods of use(23).

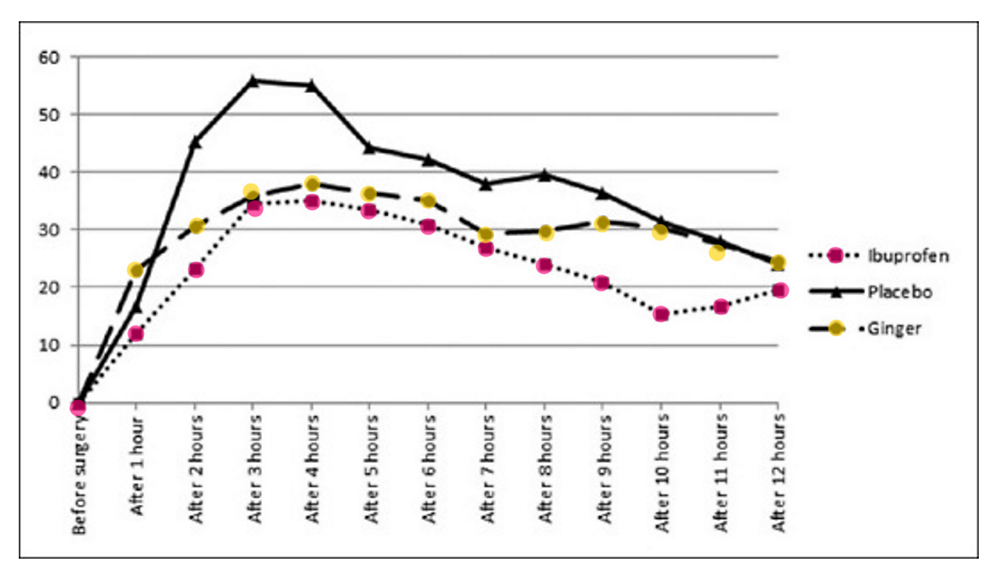

In one 2017 study, scientists demonstrated the anti-inflammatory power of ginger in humans undergoing dental treatment(24). The 67 subjects were dental patients who had to undergo a tooth extraction. Immediately following the extraction, the patients were randomly allocated into one of the three groups:

· A 500mg capsule of ginger powder taken after surgery then at 6-hourly intervals

· A 400mg Ibuprofen capsule taken at 6-hourly intervals

· An inert placebo capsule taken 6-hourly

The subsequent degree of swelling, pain and need for paracetamol (when the pain became too uncomfortable) were recorded over the following days. The results showed that both the ginger and Ibuprofen resulted in less pain and swelling, with less need for paracetamol use. Also, the ginger was equally as effective as Ibuprofen at combating pain (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Ginger supplementation and pain

Why is a study into dental pain relevant to athletes with joint pain or stiffness I hear you ask? Well, that’s because the dental pain model is a widely employed, validated, and highly standardised acute pain model, and has been shown to be the most appropriate model to investigate the onset of analgesic action. It is often used as the reference clinical pain model for the investigation of analgesic drugs, and in this model, compounds with anti-inflammatory properties provide better pain relief than conventional painkillers.

New research

While there has been much research into the anti-inflammatory and general health benefits of ginger at the cellular level, clinical studies to investigate whether ginger supplementation can improve actual physical function in active people who suffer from inflammation-related pain are thin on the ground. However, a new study by a team of scientists from Texas A&M University has looked at this very question by investigating pain perception, functional capacity, and markers of inflammation in middle-aged otherwise active men and women with a history of inflammation-related mild to severe joint and muscle pain(25).

Published in the journal ‘Nutrients’ last month, this study examined the effects of supplementing the diet with a higher-potency ginger extract on perceptions of pain and markers of inflammation in individuals who experience mild joint pain in response to physical activity. The primary outcomes (ie what the researchers were most interested in) were ratings of muscle pain, functional capacity (measured by questionnaires), and markers of inflammation. Secondary outcomes included joint flexibility, perceived quality of life, the use of over-the-counter analgesics (ie whether and how much pain relief was needed), clinical blood markers of inflammation and any reported side effects.

What they did

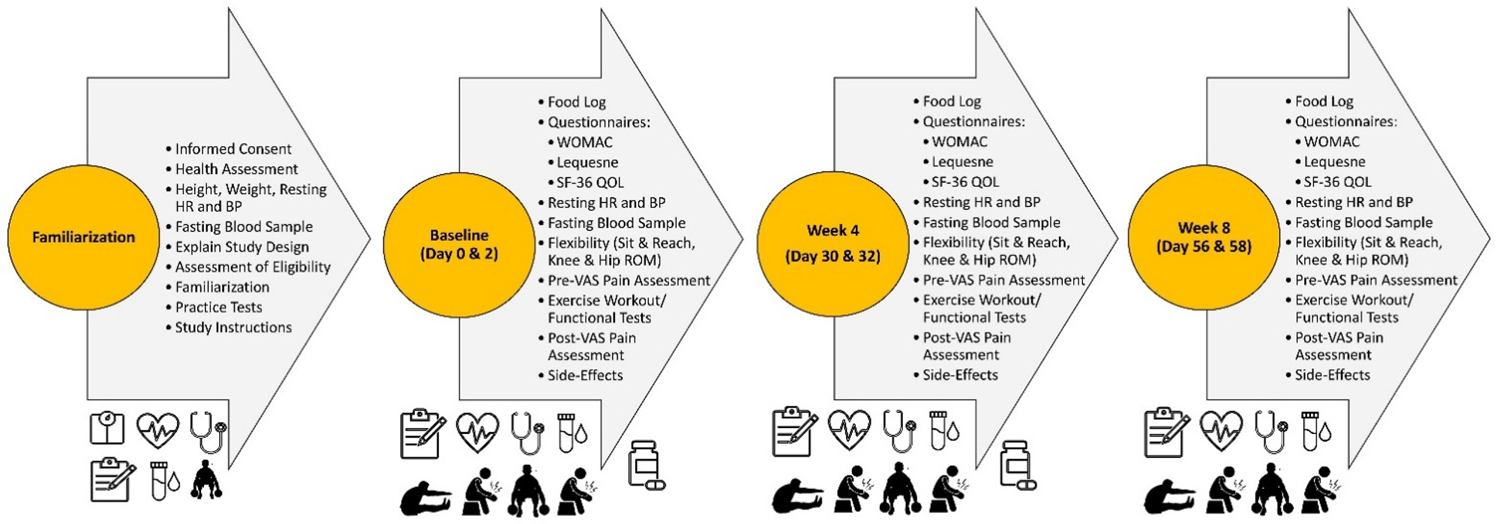

Thirty men and women (average age 56 years) with a history of mild to severe joint and muscle pain as well as inflammation participated in a placebo-controlled, randomized study. In the first phase of the study underwent a familiarization and then baseline assessment. This consisted of:

· Samples of blood taken to measure inflammatory markers.

· Completion of questionnaires about their lifestyle and the degree of pain they experienced.

· A rating of perceived pain in the thighs following application of a standardized pressure to the vastus medialis muscle of the quadriceps (outer thigh).

· Exercise function tests where participants performed 3 sets of 10 repetitions of squats/deep knee bends, while holding 30% of their body mass (repeated on days 30, and 56 of the placebo or ginger intervention), with the above test repeated after two days of recovery – ie at days 2, 32 and 58.

In addition, tests were carried out to assess range of motion and flexibility measuring the flexion of the knee and hip, with the leg that of each participant experiencing most discomfort tested and used for future tests). For pain assessments in the thigh, the participants recorded perceptions of muscle soreness using a visual scale ranging from 0 (no pain), 1 (dull ache), 2 (slight pain), 3 (more than slight pain), 4 (painful), 5 (very painful), to 6 (unbearable pain). For knee pain, pain, joint stiffness, and disability in knee and hip osteoarthritis were assessed using the Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index.

Following the familiarization and baseline procedures, the participants were randomly allocated to one of two groups:

· Ginger – ingesting 125mgs per day of ginger (standardized to contain 10% total gingerols and no more than 3% total shogaols) for 58 days.

· Placebo – ingesting a capsule of inert starch, which looked exactly the same shape and size.

The baseline tests above were then repeated on days 30 and 56, with the same measures being assessed again after two days’ of recovery (ie days 32 and 58). With regard to the exercise testing, the amount of weight lifted and the number of repetitions performed during each set were recorded. If a participant was unable to complete a set of 10 repetitions, the amount of weight was reduced to complete three sets of ten repetitions. The weight utilized for each set was summed to determine a total lifting volume. The overall study protocol is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Schematic of the study protocol

What they found

When the results from the ginger and placebo groups were statistically analyzed and compared, the main findings were as follows:

· Compared to the group that took the placebo, those that took ginger supplementation had reduced levels of muscle pain in the vastus medialis during the standardized pressure test.

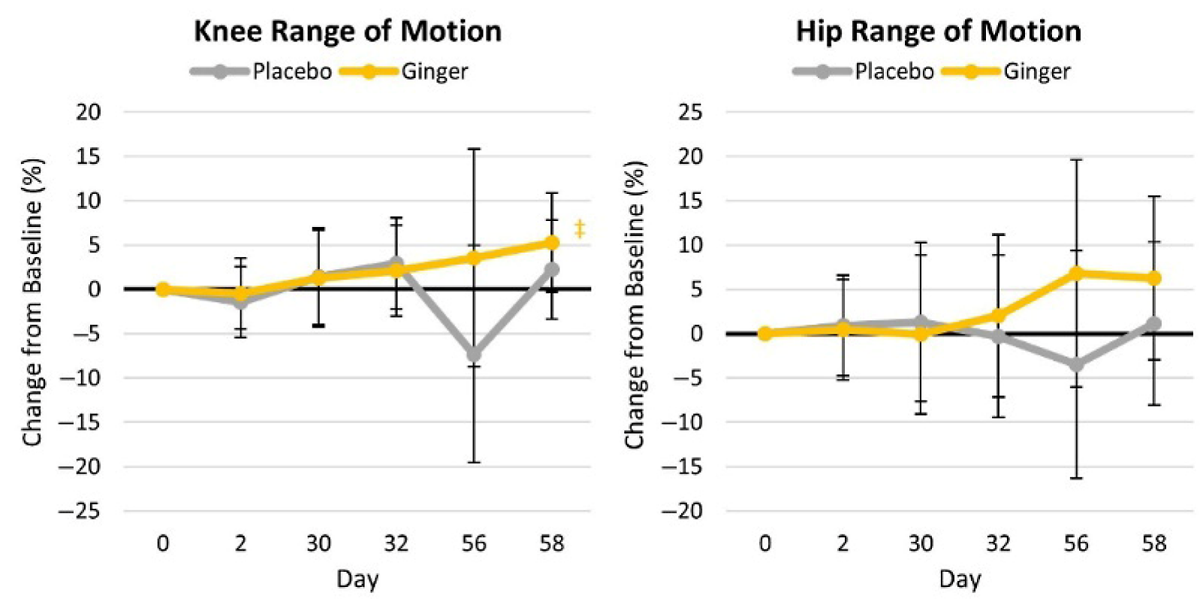

· In the functional tests to assess range of motion at the knee, joint stiffness and functional capacity, those taking ginger had improved ratings of pain, stiffness, and functional capacity compared to the placebo group (see figure 4).

· Supplementing ginger favourably affected levels of inflammatory markers (eg IL-6, INF-ϒ, TNF-α, and C-Reactive Protein concentrations), particularly during the two days of recovery following the resistance exercise (squat) challenge described above.

· There was also evidence that ginger supplementation was associated with less frequent use of over-the-counter analgesics such as paracetamol and Ibuprofen, indicating that the ginger was helping to lessen pain, thereby reducing the need for NSAID medication. However, this effect (of less frequent NSAID use) did not quite meet the threshold for statistical significance, meaning that it might have arisen by chance. A larger sample size would likely have shown this effect to be significant.

· Ginger supplementation was well tolerated with very few reported side effects.

Figure 4: Range of motion in ginger vs. placebo-supplemented participants

Summary and recommendations

In summary, the researchers concluded that low-dose ginger supplementation of 125mgs per day providing 12.5mgs per day of the all-important active gingerols lessenes perceptions of pain, improves functional capacity, and reduces several markers of inflammation in individuals who experience mild to moderate joint and muscle pain. This is almost certainly due to the fact that the gingerols exert anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, which can help reduce pain in individuals with chronic muscle and knee pain. Moreover, since the ginger supplementation was well tolerated, taking ginger may be an option for those who suffer with inflammation-related knee pain, and who want to reduce the reliance on and risks of over-the-counter pain medications.

For older athletes who struggle with intermittent or chronic joint pain/stiffness, there’s a good rationale for experimenting with ginger supplementation. It’s safe, has very few side effects, provides health benefits above and beyond reducing inflammation, and importantly, it’s relatively inexpensive. However, you need to be aware that not all ginger supplements are created equal. The species of ginger and the way that growers have cultivated it can affect the strength and effectiveness of its analgesic effects - primarily due to differences in the natural phytochemical composition, especially the concentrations of active compounds like [6]-gingerol, [6]-shogaol, [8]-gingerol, and [10]-gingerol. The key therefore is to choose a supplement with a standardized potency of gingerols. Choose a reputable brand too, preferably one that uses organic ginger and that can provide a certificate of analysis verifying the gingerol content. In the study above, this daily supplemental gingerol amount was 12.5mgs, which is the kind of amount you should look out for. Also, ginger supplements are best taken with food; a good time is in the morning after breakfast. Finally, don’t forget that diet matters too; keep your diet as whole and natural as possible, while minimizing your intake of ultra-processed foods. That won’t just help combat inflammation, but will likely enhance your performance too!

References

1. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25(16):1889-1912

2. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 11, 43–50 (2023)

3. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2025 Mar:130:105731

4. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2025 Aug;38(4):e70096

5. Nutrients. 2025 May 28;17(11):1843.

6. Ageing Res Rev. 2018 Sep:46:42-59

7. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG. 2012;18:2147

8. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018 Nov;28(11):2252-2262

9. Sports Med. 1999;28:383–8

10. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:13

11. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 86, 108486

12. Nutrients 2024, 16, 741

13. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 929, 177–207

14. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1310–1327

15. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 816364

16. J. Pain 2010, 11, 894–903

17. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 146142

18. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 104, 108975

19. Molecules 2022, 27, 7223

20. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:783–9

21. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:9–12

22. Arch Iran Med. 2005;8:267–71

23. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:231–7

24. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2017 Jan-Feb; 14(1): 1–7

25. Nutrients. 2025 Jul 18;17(14):2365. doi: 10.3390/nu17142365

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.