Weight management: playing fast and loose with strength?

Fasting regimes can be very effective for fat loss but what is the long-term impact on strength and is there a price to pay? SPB looks at new research

In most sports, the loss of excess body fat almost always produces enhanced performance. When excess fat is shed, not only is power-to-weight ratio (the amount of power available to each kilo of bodyweight, which is a fundamental determinant of performance – see this article) improved, there are other benefits too. These include increased agility, and a reduced injury risk through reduced impact loading, especially in weight-bearing sports such as running.

Routes to leanness

The age-old question for athletes of course is how best to shed excess pounds and keep them off without resorting to extreme diets or training schedules that might lead to muscle mass loss, reduced strength and power, increased risk of injury, and even illness. The go-to method recommended by most dieticians is the use of mild calorie restriction, over an extended time period(1,2). But while this can be an effective route in the general population, it can be more difficult for athletes in training, who generally need significantly more calories than their sedentary counterparts in order to fuel training.

In recent years, other methods of weight management have found favour among athletes, one of which is intermittent fasting, which has been shown to be equally as effective for weight loss as conventional calorie controlled diets(3). Indeed, some evidence suggests that intermittent fasting may be even more effective than continuous calorie control(4). A variation on this is ‘alternate day fasting’, which has also been demonstrated to be an effective route to weight loss and improved body composition(5), while yet another method for which robust evidence exists is the use of meal-replacement drinks to replace the main meal of the day(6).

Leanness without calorie restriction

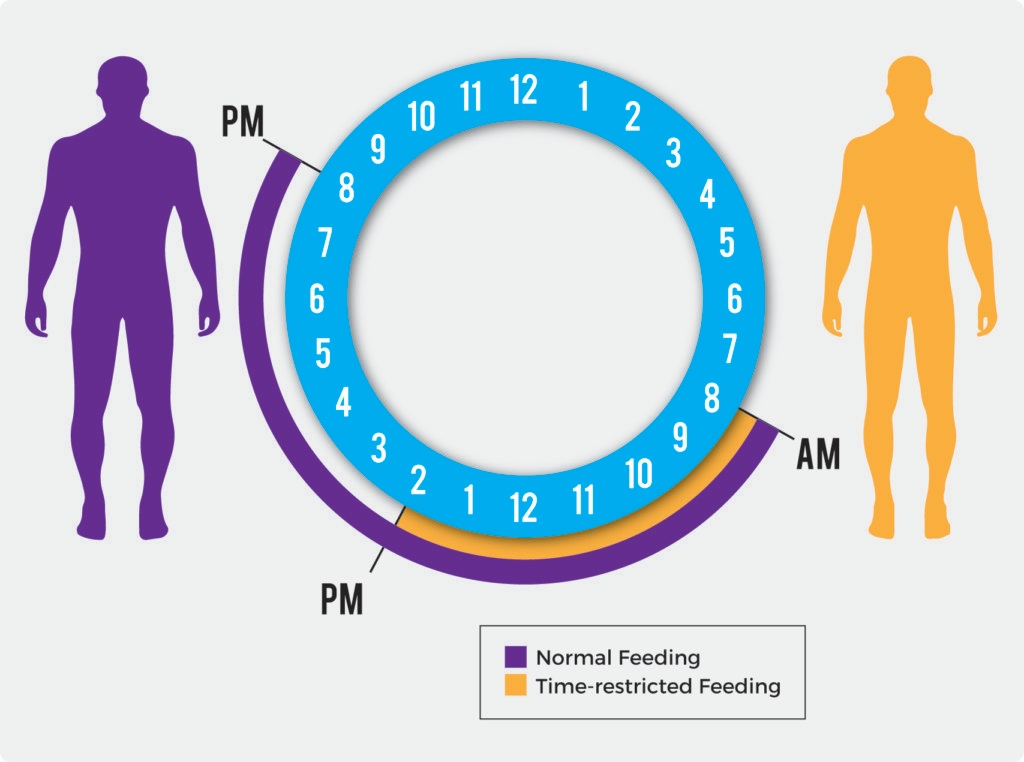

There’s another alternative to fasting for weight loss, which has become increasingly popular in recent years – time restricted feeding or TRF for short. The idea of TRF is that instead of eating freely throughout the day, meals and calories are consumed within a relatively narrow time interval each day of around eight hours (see figure 1). The theory behind TRF is that by having 16 or so hours in each 24 hours as ‘food intake free’, fat burning gene activity is upregulated, helping to shed excess body fat. In this respect, TRF can be considered as a short term fast; rather than lasting a day or two, it lasts no more than 16 hours.

A key point however is that TRF can be continued for many days by athletes as it does not involve a restriction in the number of calories or amount of protein and carbohydrate consumed. It only affects the time window in which the normal calorie intake is consumed. A number of studies (but not all – see this article) have shown that restricting food intake to a 4-12 hour slot in the day, without reducing calorie intake, is associated with improved body weight maintenance, and that TRF can therefore be considered as a useful weight reduction strategy(7-9).

Figure 1: Time–restricted feeding (24-hour clock)

The problem with fasting

While the above strategies for weight reduction and management can work well in the general population, they may struggle to fulfil the needs of athletes. An athlete’s nutritional requirements (including calorie intake) are driven very much by training and recovery needs. Performing a fast or restricting calorie intake in the hours or day following a training session or competition could be a recipe for failure because these are the very times athletes need to replenish muscles with glycogen (carbohydrate) and consume adequate protein for muscle tissue repair and growth (see this article on the fundamentals of nutrition and recovery). In short, the training and competition you perform should direct your nutritional habits, not the other way round!

Looking at this issue in more depth, the problem is that the biochemical and physiological changes that fasting induces are very mixed. Some may be advantageous in certain circumstances – for example fasting-induced ketogenesis, which tends to favor fat oxidation over carbohydrate metabolism, conserving muscle glycogen stores, and thus benefiting endurance performance(10). Other are definitely disadvantageous, an example being the reduced energy availability associated with fasting/calorie restriction, which can impair performance during high-intensity activities or anaerobic exercise, where glycogen is the primary fuel source(11).

Over a longer timescale, prolonged calorie deficits can result in impaired muscle protein synthesis and altered levels of hormones like insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF−1), which can affect (harm) strength, recovery, and training adaptations(12). In addition to physiological mechanisms, fasting and calorie restriction can also impact exercise performance via altered mood, motivation, and perceived exertion, making it harder to adhere to a training program and perform well(13). Moreover, imposing rigid timing or calorie limits on your daily diet runs the risk of causing disordered eating patterns or reduced exercise enjoyment, especially in the long-term(14). This may be especially the case in athletes, who might be more compulsive in the their behaviours (see this article on exercise addiction)

Fasting/calorie restriction and athletes

Fasting and TRF can affect metabolism in different ways, but how does this translate into athletic performance? The evidence is rather mixed. Some suggests that highly-trained athletes exhibit greater resistance to fasting-induced fatigue - possibly due to superior adaptations in sleep quality, hydration management, and metabolic efficiency – whereas amateur athletes or less-trained individuals tend to experience greater declines in performance(15-17). Also, female athletes tend to show better fat oxidation and greater resistance to metabolic swings when fasting than males(18).

When it comes to long-term strength performance and fasting, even less is known. Two studies found that compared to a standard diet, resistance training combined with TRF over an 8-week period preserved fat-free mass (FFM) while reducing fat mass (FM), without compromising muscle strength (19,20). However, recent research has also found that longer fasts can significantly dent performance, inducing a loss in peak oxygen uptake of 13% and drop in lean muscle mass of over 4kgs(21)!

To add confusion, a meta-analysis of 11 studies found that Ramadan fasting had a detrimental effect on mean and peak power during high-intensity activities, particularly in the morning, despite having minimal effects on aerobic performance, strength, and jump height(22). This was in contrast to another meta-analysis of 28 studies demonstrating that TRF protocols significantly improved maximal oxygen consumption while strength and anaerobic capacity were unaffected(23). Similarly, simple calorie restriction shows a dichotomy of outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis demonstrated that while mild calorie restriction can promote strength gains and increases in lean mass, severe calorie deficits greater than 500kcals per day may compromise muscle strength and recovery(12).

New research

What are the true effects of short-term fasting/calorie restriction on performance and training adaptations in athletes? Is physical performance impacted, and if so in what way? A brand new systematic review and meta-study (where all the previous findings are methodically reviewed and then the data is pooled and analyzed to come up with robust overall conclusions) has attempted to answer this question – in particular, the effects of fasting/TRF/calorie restriction on various strength parameters(24). Published in the journal ‘Nutrients’, this study by an international team of researchers systematically evaluated the effects of intermittent fasting (IF) and calorie restriction (CR) on exercise performance and body composition in adults aged 18 to 65 years.

What they did

The researchers scoured the scientific databases for all previous studies on this topic that met all the following criteria:

*Studies where the intervention duration was four weeks or more and involved various types of training - aerobic training, high-intensity interval training [HIIT], or resistance training.

*Studies that were published in the scientific literature and had been peer-reviewed (ie the findings verified by other experts in the field).

*Studies that assessed the effects of IF and CR combined with exercise vs. exercise alone with no fasting or calorie restriction (ie control) on various measures in adults aged 18 to 65 years including:

- Body weight

- Aerobic capacity (VO2max)

- Measures of strength including handgrip strength, bench press strength, knee extensor strength, leg press strength

- Measures of explosive power using the countermovement jump [CMJ]

- Body composition (including body mass index [BMI], fat-free mass, fat mass, and body fat percentage (BFP)

In all, 35 studies were identified as meeting the criteria, containing a total of 1266 participants, both male and female, and with a range of activity and fitness levels from sedentary and overweight to highly trained athletes. The full list of studies included can be found in table 1 of the paper. The data from all these studies was pooled and statistically analyzed to come up with overall findings.

What they found

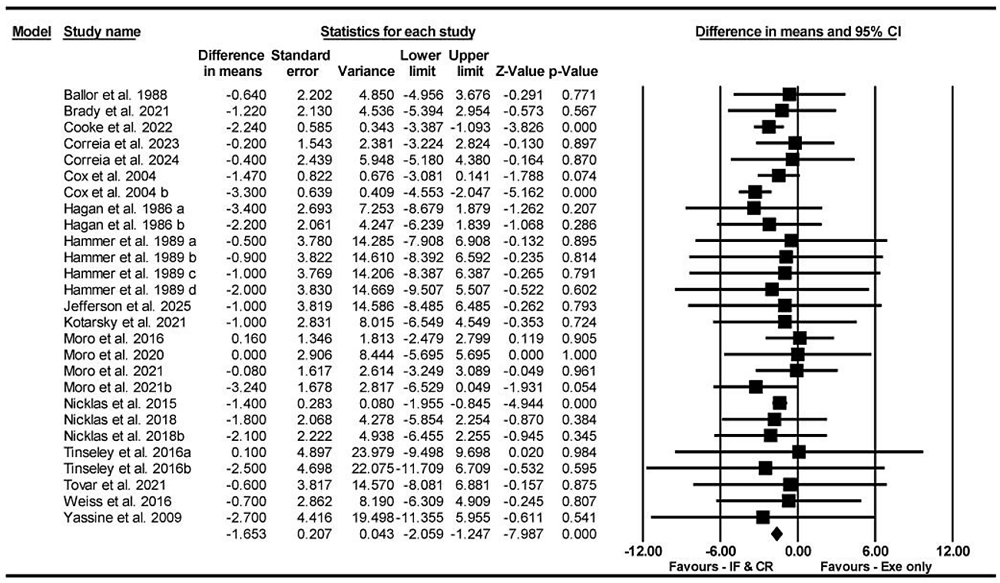

The first main finding was that neither fasting nor calorie restriction in a training program affected aerobic capacity gains compared to training while eating normally – good news for endurance athletes who use intermittent fasting/calorie restriction as part of a weight management plan! Also, and perhaps unsurprisingly, a training program combined with intermittent fasting or calorie restriction resulted in greater fat loss than exercise alone. However, balanced against this was that fat-free mass also declined when fasting/calorie restriction was added to training (see figure 2), although this effect was observed more in less trained subjects rather than highly-trained athletes.

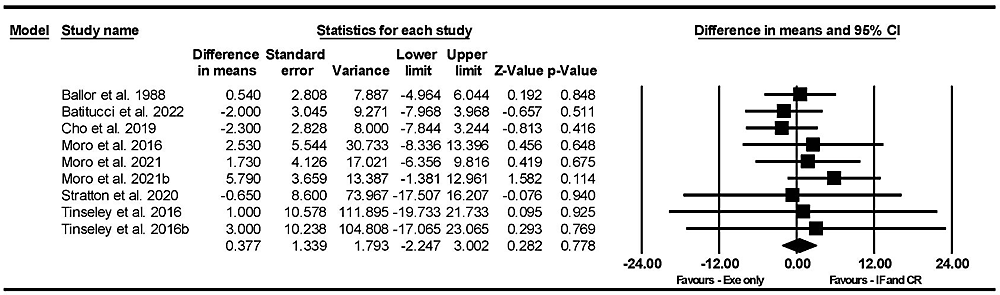

The good news continued when it came to measures of strength; compared to training while eating normally, neither fasting nor calorie restriction negatively affected bench press strength (figure 3), leg extension strength or explosive strength gains as measured in the countermovement jump. In fact, when it came to handgrip strength gains, training while undergoing intermittent fasting or calorie restriction actually seemed to slightly enhance the outcome compared to normal eating!

Figure 2 (top): Fat-free mass in exercise plus IF/CR vs. exercise alone

Figure 3 (below): Bench press strength in exercise plus IF/CR vs. exercise alone

Practical implications for athletes

These findings are valuable for athletes because they suggest that intermittent fasting strategies such as 24-hour fasts and TRF, as well as calorie restriction can be effectively integrated into exercise training without negatively impacting most measures of physical performance. While this new research is perhaps not surprising when it comes to endurance performance (remember that simply reducing body/fat mass helps improve power-to-weight ratio even without gains in maximum aerobic capacity), the findings on strength are intriguing for athletes where maintaining maximum strength and power is important. In short, if you are a strength athlete who needs to lower your body mass/fat level, using intermittent fasting strategies or calorie restriction over a period of time won’t necessarily mean you will be sacrificing potential strength gains during that period.

That said, there are some important caveats to add. Firstly, the authors noted that all athletes are different with psychological and metabolic characteristics that vary from person to person. Therefore, a weight-loss strategy that works for one athlete may not be suitable for someone else. From the data presented earlier in this article, we known that training status and biological sex play can greatly affect tolerance to fasting; highly trained athletes, especially female athletes tend to cope well, while male athletes who are only moderately or recreationally trained are more likely to struggle. So if you find that imposing rigid timing or calorie limits on your daily diet affects your well being and reduces your exercise enjoyment, you may be better off just sticking to mild calorie restriction - you need to experiment for yourself.

Secondly, timing and degree matters. For example, if you are undertaking a 24-hour fast, you should only be scheduling very light workouts or rest during that period. If you are using TRF, you need to bear in mind that training at the end of that 8-hour eating window will leave you little or no room for recovery nutrition afterwards. You could train just before the start of the window, but after having not eaten for 16 hours, you will probably need to avoid hard or long workouts. Perhaps the best option is to have a light breakfast, train then use the rest of the 8-hour window for recovery nutrition. The same caveats apply to daily calorie restriction. A mild calorie deficit of no more than 500kcals per day shouldn’t impact your ability to train and recover too much, but common sense is still needed. With more severe calorie restriction, training volumes and intensity will need to be dialled back accordingly.

A final note concerns absolute muscle mass. While the fasting, TRF and calorie restriction strategies did not affect strength outcomes, they did result in a loss of some muscle mass compared to exercise plus normal eating. This suggests that for athletes trying to build base strength, fasting or severe calorie restriction is not recommended. A good example might be an athlete returning to sport after a lengthy layoff due to injury. While it might be tempting to undertake fasting during the injury rehab process to keep excess weight at bay, this could be detrimental in the longer term since it might impede muscle mass development just at a time when it is needed for muscle healing and remodelling!

References

1. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015; 23:7–15

2. Obes Rev . 2017 Oct;18(10):1122-1135

3. Can Fam Physician. 2020 Feb;66(2):117-125

4. Nutrients. 2022 Apr 24;14(9):1781

5. Front Nutr. 2020 Nov 24;7:586036

6. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021 Aug;121(8):1551-1564.e3

7. Science (New York, NY). 2018; 362:770–775

8. Cell Metab. 2015; 22:22–798

9. Science. 2016; 354:1008–1015

10. Nutrients. 2024;16:1849

11. Nutrients. 2024;16:168

12. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2022;32:125–137

13. Physiol. Behav. 2015;139:524–531

14. Dis. Markers. 2022;2022:5653739

15. Sports Med. 2020;50:1009–1026

16. Saudi Med. J. 2005;26:616–622

17. Chronobiol. Int. 2008;25:697–724

18. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:3646–3652

19. J. Transl. Med. 2016;14:290

20. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019;110:628–640

21. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017;17:200–207

22. Sports Med. 2020;50:1009–1026

23. Nutrients. 2020;12:1390

24. Nutrients. 2025 Jun 13;17(12):1992. doi: 10.3390/nu17121992

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.