You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Endurance performance: Paying the price of mental fatigue

SPB looks at new research on the true impact of mental fatigue before a session of endurance exercise, and what it means for athletes seeking peak performance

More than 2,000 years ago, Siddhartha Gautama, the Indian philosopher and the founder of Buddhism proclaimed that “The mind is everything. What you think, you become.” Since then, the connection between mind and body has well understood across the ages, but its significance has only recently been appreciated in the context of sport performance. Yes, it’s true that sports psychology has long been a component of fine tuning an athlete’s expectations and mental approach for a race event. However, the impact of the brain on actual physical performance has only become a serious topic of research during the past couple of decades.

Brain and performance

In a number of previous SPB articles, we have explored evidence clearly demonstrating that the brain is the master controller of the fatigue your muscles experience when performing exhaustive exercise. In short, the fatigue you experience during exercise isn’t just a biochemical phenomenon occurring in muscles and blood – it’s also a neurological phenomenon dependent on the brain and your thoughts/perceptions. This explains why certain types of music can enhance performance and lower perceived effort levels(1,2), and even how different expectations of an exercise session can impact how much effort can be sustained(3).

Mental fatigue and performance

Given the powerful link connecting brain to exercise performance, it would be incredible if loading up the brain with mental and psychological demands before exercise didn’t affect performance, and this indeed is what we find. In a previous SPB article, Andrew Sheaff highlighted a recent review of all the research investigating whether performing resistance training while mentally fatigued would result in worse performance compared to performing exactly the same resistance training without prior mental fatigue(4). As Andrew explains, the results were very clear: the inclusion of mentally fatiguing activities prior to intense resistance exercise significantly reduced the number of repetitions subjects were able to achieve during a set. Indeed, the presence of mental fatigue, even in the absence of physical fatigue, negatively impacted performance.

There’s also plenty of recent research the impact of mental demands during exercise itself – so-called ‘dual tasking’. The research on this topic is fairly unambiguous: adding extraneous cognitive loading (ie mental demands) during a motor task (ie exercise) will typically lead to worse performance, as compared to normal or single-task conditions(5). Good examples of this include:

· Worse performance in soccer players who try to solve arithmetic problems while juggling a ball(6).

· Poorer time trial performance in cyclists asked to monitor multiple forms of feedback during their effort(7).

· Reduced accuracy, balance and smoothness when performing exercise requiring good motor coordination(8-10).

Prior mental fatigue and endurance

In the examples above, we cited research showing that ‘dual tasking’ during exercise can negatively affect endurance performance and also that prior mental fatigue has a detrimental effect on resistance training and carrying our strength tasks. But can prior mental fatigue negatively affect endurance performance? In other words, should you expect to turn in poorer times for a training session or evening event after for example a demanding day in the office or after a long and stressful commute?

Before we answer that question, let’s try and define what we mean by ‘mental fatigue’, which is a fairly broad term. Technically, mental fatigue has been defined as the psychobiological state (ie a state brought about by both psychological and biological processes) induced by a sustained cognitive effort(11). This mental fatigue manifests itself by subjective feelings of tiredness and lack of energy, alterations in brain function and impaired cognitive function (ie reduced ability to mentally process information)(12).

Evidence from swimming

Despite plenty of anecdotal evidence from coaches and athletes about the negative effects of prior mental fatigue on their endurance performance, researchers have only recently started to investigate this phenomenon using carefully designed studies. However, the experimental evidence accumulated over the past 15 years most definitely suggests that prior mental fatigue negatively affects endurance performance.

For example, a study with young swimmers observed a reduction in 1500m freestyle performance following a 30-min Stroop task (a demanding mental task where participants have to continually distinguish between the actual color of the ink in which a word describing a color is written in and the meaning of the word) in 12 of 16 athletes(13). The pacing analysis showed that the participants were slower when they had become mentally fatigue beforehand in every 300m split (ie at 300, 600, 900, 1,200, and 1,500m).

In another study, international-level swimmers used social media for 30 minutes to induce mental fatigue before performing 50m, 100m and 200m swimming time trials in the pool(14). In the 50m time trials, prior mental fatigue induced no effect – perhaps to be expected for a race when concentration in only needed for less than 30 seconds. On the other hand, in the 100 and 200m time trials, inducing prior mental fatigue resulted in a significant performance drop.

More research on the effects of prior mental fatigue on swimming performance comes from amateur triathletes(15). On three separate occasions and in a random order, seven recreational triathletes watched a documentary, utilized a smartphone, or performed mental tasks where continual responses were required on a keyboard, then performed a 15-minute warm-up followed by 6 × 200m at constant pre-set speed plus one 200m at maximal effort. The results of this study showed no negative effect of prior mental fatigue, which is contrary to other studies. However, this study had limitations in that the sample size was small (just seven athletes), and there was no control condition (ie just doing nothing before the swim). Also, this study used recreational athletes, whereas most of the previous studies have used either professional/elite or very well trained amateurs.

New research

To try and clarify the impact of prior mental fatigue on endurance performance, we can turn to a new study by a team of Italian researchers that has been investigating the effects of mental fatigue on perception of effort and performance in national level swimmers, details of which have just been published in the prestigious journal ‘Frontiers in Psychology’(16). In this study, the researchers set out to examine the effects of prior mental fatigue on endurance performance, which was measured with a 400-meter front-crawl test. In addition, they sought to discover if and how prior mental fatigue impacted on measures of blood lactate, heart rate and perceived exertion while the swimmers performed an extended steady-state swim consisting of 12 sets of 100m performed at the swimmers’ normal lactate threshold.

What they did

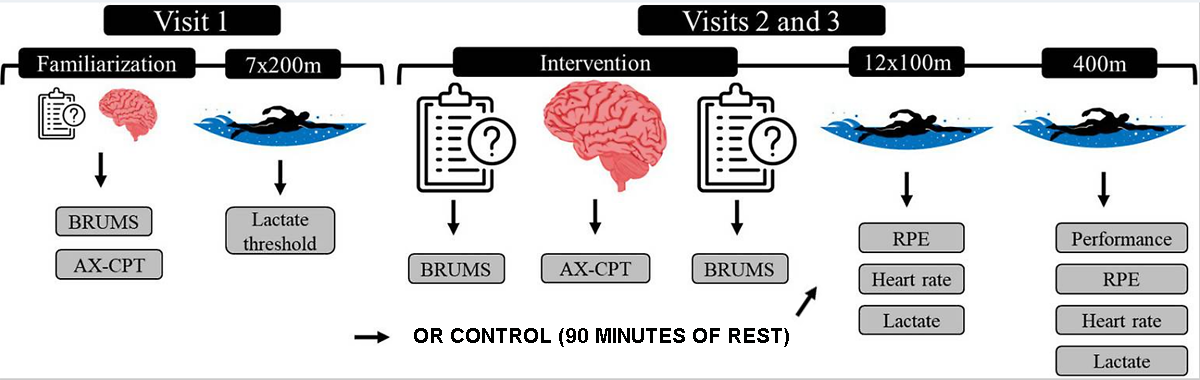

Ten swimmers (six men and four women) were recruited to participate in the study and all completed it. All the swimmers were ranked in the top ten nationally in their respective events, with six having competed internationally – ie of elite status. The first step was a familiarization trial where all the swimmers attended the lab and acquainted themselves with the ‘AX-CPT’ challenge, which was used to induce mental fatigue in the later experimental trials. In this test, the swimmers were asked to sit in front of a computer screen in a silent room where a sequence of variable random letters, one at a time, was presented them. Using the mouse, they had to respond but only when they observed a 2-letter sequence of the letter ‘A’ followed by the letter ‘X’. This ‘A-X’ sequence occurred in 7 out of 10 instances, with the other 30% being random combinations to throw the swimmers off course!

The second part of the familiarization session consisted of a set of 7 × 200m swimming repeats, each separated by five minutes. These repeats started off gently but gradually increased in intensity until they became maximal effort. By taking blood samples in between each 200m swim, the researchers were able to individually determine the speed of each swimmer’s lactate threshold (the swimming speed at which blood lactate begins to rapidly accumulate), which would be used in the next stage of the experiment.

The experiment

In the next stage of the study, all the swimmers attended on two separate occasions in a fully rested state and performed a 600m warm up in the pool followed by a set of 12 x 100m repeats at their pre-determined lactate threshold. This was then followed by a 400m front-crawl performance test, which the swimmers were asked to complete in the fastest time they could. In all respects, these two trials were identical except the period before the trial (the order of trials was chosen at random):

· Mental fatigue condition – in this trial, the swimmers completed the AX-Continuous Performance Task for 90 minutes beforehand to induce mental fatigue.

· Control condition - in this trial, the swimmers simply rested for 90 minutes beforehand.

Before and after the AX test, mood scores were taken (to determine mental fatigue). Heart rate, lactate and perceived exertion (RPE) were measured during the 12 x 100m segment and again after the 400m flat-out time trial, where times were also recorded. A graphic showing the overall protocol for the experiment is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Experimental protocol

What they found

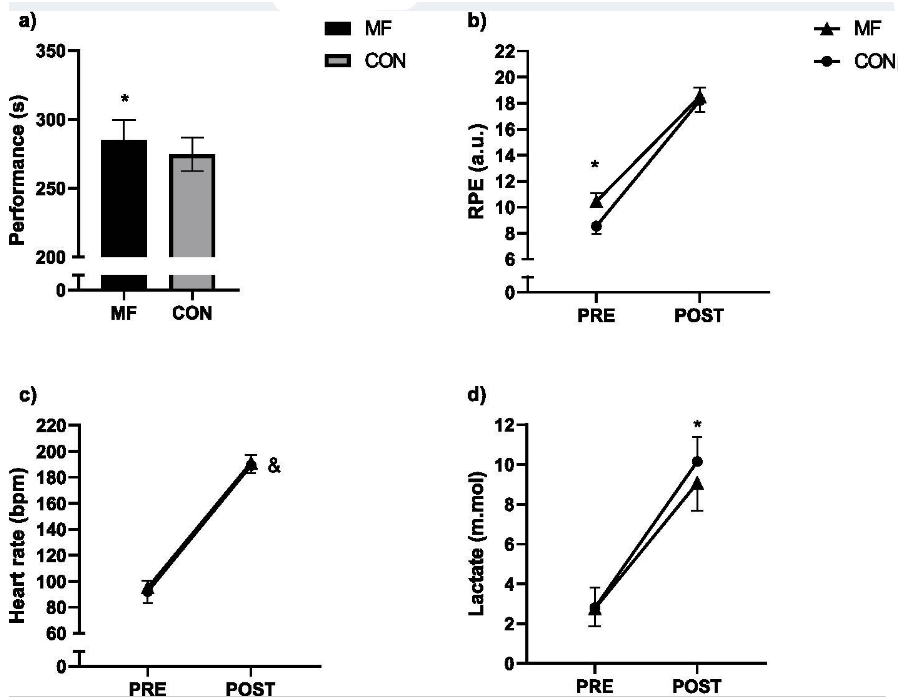

The first finding was that (unsurprisingly), when the swimmers performed the 90-minute AX-CPT task, they experienced a notable level of mental fatigue afterwards. Obviously, there was no mental fatigue in the control condition where they simply rested for 90 minutes. When tested during the constant (submaximal) speed 12 x 100m test, the swimmers experienced much higher levels of perceived exertion following the AX-CPT task compared to the control condition (90 minutes of rest), even though their heart rates and blood lactate levels were no higher. In short, steady-state, submaximal exercise felt significantly harder to perform following a mentally demanding task. Of even greater importance was the difference in performance during the 400m time trial; in the control trial, the swimmers averaged 4mins 37secs for the 400m whereas in the mental fatigue trial, they averaged 11 seconds longer, taking 4mins 48secs to complete the distance. Figure 2 shows the differences between the mental fatigue and the control condition.

Figure 2: Differences between mental fatigue and control conditions

Related Files

Implications for athletes

This study provides further evidence that mental fatigue can seriously impact performance. In the 400m swim time trial, the athletes when mentally fatigued showed a mean performance reduction of 3.9%. This is a huge difference, especially in competitive sport. To illustrate this fact, consider that the differences between the first and third place in the 2024 Olympics for the men’s 200m, 400m, and 1,500m events were 0.04%, 0.2%, and 0.6%, respectively FINA, 2024, www.worldaquatics.com/.

Another point worth considering is that some researchers have previously suggested that elite athletes who are more highly trained and better at ‘focussing’ on the task at hand are not significantly impacted by prior mental fatigue. But this research shows that even elites can take a big hit with mental fatigue. Remember too, that this mental fatigue was induced by a simple mental task challenge at a desk; had this been fatigue induced by mental challenges with a big helping of emotional stress on the side (as is the case in many jobs), the negative impact most likely would have been more severe (a good topic for a future study!). The authors also noted that the negative impact of mental fatigue after a 90-minute task was higher than in the study above on 1,500m swimmers, who experienced a 1.2% drop in performance after a 30-minute task(13). This suggests that the longer a mentally demanding task is carried out before exercise, the greater the negative impact.

In terms of applying this knowledge, the key take-home message is that your mental state – particularly levels of mental fatigue – prior to exercise can profoundly affect that exercise. At the very least, feeling mentally tired will make sub-maximal exercise ‘feel’ harder, even though it isn’t. When it comes to competition and maximal exertion, prior mental fatigue will negatively impact your performance. Given the mental fatigue effect, and how it harms performance, there are two strategies to consider.

· Firstly, try and schedule your high quality training sessions away from days/evenings where the previous hours have been mentally very demanding. For example, if you know that Wednesdays and Thursday are always very demanding at work, schedule them for ‘easy’ training days in your diary. Regardless, try to avoid taking on tasks such as dealing with work matters or doom-scrolling on social media just before you train.

· When it comes to competition, you will instead have to adapt what you do in the run up to the event. That could mean selecting events that take place at times of the season or on days of the week when you know your workload is lighter, or you have less family commitments etc. For events where there is no flexibility, try and make sure you plan well ahead to avoid stress in then two or three hours beforehand. For example, if you need to travel to an event, leave much earlier than you need to, get there early and then you can just rest. Importantly, don’t take on any mental tasks or worries just before your event. Switch your phone off and instead relax with uplifting music!

References

1. Percept & Motor Skills 83, 1347-1352, 1996

2. J of Sport Behavior 20, 54-68, 1997

3. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018 May;58(5):744-749

4. Motor Control. 2022 Dec 12;27(2):442-461

5. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (4) (2021), p. 1732

6. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61 (2) (2020), pp. 168-176

7. Front Psychol. 2020 Dec 23;11:608426. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608426. eCollection 2020

8. Journal of Motor Behavior, 52 (2) (2020), pp. 204-213

9. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36 (5) (2018), pp. 513-521

10. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 117 (2) (2013), pp. 411-426

11. J. Appl. Physiol 1985. 106, 857–864

12. Cutsem J. V., Marcora S. (2021). “The effects of mental fatigue on sport performance: an update” in Motivation and self-regulation in sport and exercise (London: Routledge)

13. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci 2018. 30, 208–215

14. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2020. 93, 120–129

15. Sensors (Basel). 2023 Jun 23;23(13):5837

16. Front Psychol. 2025 Apr 9:16:1520156. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1520156. eCollection 2025

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.