You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Endurance for the long haul: learning from the ultra-elites

What are the fundamental training structure requirements for athletes seeking long-term endurance performance gains over many years? SPB looks at the implications of new research on XC-skiers

We all know that professional endurance athletes such as Tour de France cyclists Hawaiian Ironman winners and elite marathoners are extremely fit and possess tremendous endurance capacity – as well as high levels of mental resilience. But how do these athletes get to the top? Obviously, having great genetics is a pre-requisite, and of course optimum nutrition helps too. But what is it about the training practices of these elite endurance athletes that allows them to progress over time from being merely very good to top-level, world-class performers?

Taking a long-term approach

The question of how to achieve endurance greatness is very commonly asked – not just by athletes but by their coaches too. It’s not surprising therefore that this is a topic that has been extensively researched over the year by academics and sports scientists. Naturally, much of this research has focused on the training practices of these athletes, trying to unpick the data to see which practices lead to ‘only’ to high levels of performance and which practices can take athletes right to the top – ie world class level(1,2). Perhaps unexpectedly, the research to date shows that the long-term development pathways of the world’s best endurance athletes are highly diverse(3,4). In plain English, there doesn’t seem to be a ‘one size fits all’ formula for attaining world class performance; instead, a number of different routes may get you there.

One reason why the data on the best practices for attaining world-class performance is still rather opaque is that many of the previous studies on this topic have tended to use training ‘snapshots’. For example, the training diaries and actual training sessions of athletes may have been analyzed and tracked for a few weeks or months, or even over a whole season. But while useful, this data doesn’t take into account the long-term context – ie how the training characteristics and the athlete’s development have evolved over three or five or even ten years. World class performances don’t just pop up out of nowhere; they are the result of many years of hard work and training dedication. So without knowing how that ‘training snapshot’ gleaned from a study fits into the bigger picture that has evolved over many years, it’s very hard to ascertain what training characteristics these world-class athletes might have in common.

Demands of X-country skiing

Although more of a winter endurance sport rather than all year round, cross-country (XC) skiing is renowned for its incredible endurance demands. The large number of major muscle groups recruited during XC skiing means that oxygen consumption levels can be incredibly high. Indeed, the unique physiological demands of this sport is the reason that world-class XC skiers are characterized by some of the highest peak oxygen uptake (VO2max) values ever recorded(5). Whereas the very best world class male runners and cyclists might achieve a VO2max in the high 80s (mls of oxygen per kilo per minute), the highest ever VO2max figures ever achieved are in world class XC skiers, with 96mls/kg/minute(6). The VO2max for female XC skiers are no less impressive, typically ranging 70 to 80mls/kg/min – significantly higher than in female runners and cyclists performing at the same level(7).

Being at the pinnacle of endurance sports from a physiological demand perspective, delving into what makes and shapes world-class XC skiers could be a good option for scientists trying to tease out the key training characteristics required to make a world-class endurance athlete. As in other sports, a good body of research exists, which has looked at training diary data of XC skiers over relatively short time periods. Studies have suggested that endurance training accounts for more than 90% of the total training volume, and of this, around 90% is executed as low intensity training, with the remaining 10% consisting of moderate- and high-intensity training, primarily performed as competitions and interval sessions(8).

But as in other endurance sports, how best to structure and adapt training duration and intensity over the longer term in order to bring out the best in XC ski athletes remains poorly understood. In fact, only two previous studies have reported on the long-term development of athletes - in particular, tracking athletes through the transition from junior to senior status. In one of these – a case study reported on a world-leading female XC skier where there was an 80% increase in annual training volume - from 522 hours in her junior years to 940 hours in senior years(9).

In another study on 17 world-class XC skiers, researchers found an average increase of 203 hours annually in the skiers’ training volume(10). However, while providing some insight, one case study (considered the lowest robustness of evidence) and one other study comparing just one junior and senior XC ski season doesn’t really provide the quality of evidence needed to determine how endurance athletes can best develop their training structure over a period of years to bring out the very best in their abilities.

New research

To try and provide some more definitive answers on the best approach for the long-term development of endurance, a team of Norwegian researchers has just published new research on XC ski athletes(11). Published in the journal ‘Sports Medicine Open’, what makes this research unique however is that the information on training practices was not gathered from a snapshot, but from three decades of data!

Six Norwegian female world-class XC skiers (categorized as tier 5 – ie world class(12)) were recruited for the study. To be included, all the athletes had to meet the following criteria:

· All athletes competed at the senior level between 1988 and 2023.

· Athletes who had achieved individual medals in the Olympic Winter Games (OWG) or World Championships (WCH).

· Had systematically recorded their day-to-day training in detail from junior right through to senior & world-class level.

· Had performed physiological testing at the Norwegian Olympic Training Center.

These athletes were then further divided into two groups based on their competitive results through their careers: the researchers assigned a class of ‘tier 5+’ to the athletes who had won eight or more medals from OWG/WCH, and a class of ‘tier 5’ to the athletes who had only(!) have won four or fewer medals. The key point was that as seniors, the group of tier 5+ athletes reached the podium in the WC, WCH, and OWG more than five times as often as the tier 5 athletes. In effect, what the researchers were trying to do was discover which training factors were most likely to be important for creating the very best world-class athletes – the crème de la crème.

What they did

The goal of the study was to investigate the development of training characteristics and factors that determine physiological performance over a long period of time. Therefore, to cover both the transition from junior to senior levels (19–23 years) and the point of reaching world-class level, 10 to 15 seasons of training were analyzed for each athlete, covering the period from junior age to world-class level. The researchers compared tier 5 athletes with tier 5+ athletes at the same time points in their careers. In addition, to minimize the influence of time-dependent improvements in on training and performance knowledge and practices (as we learn more, training practices tend to improve), each athlete was paired with another athlete performing at the same time-period within the same decade.

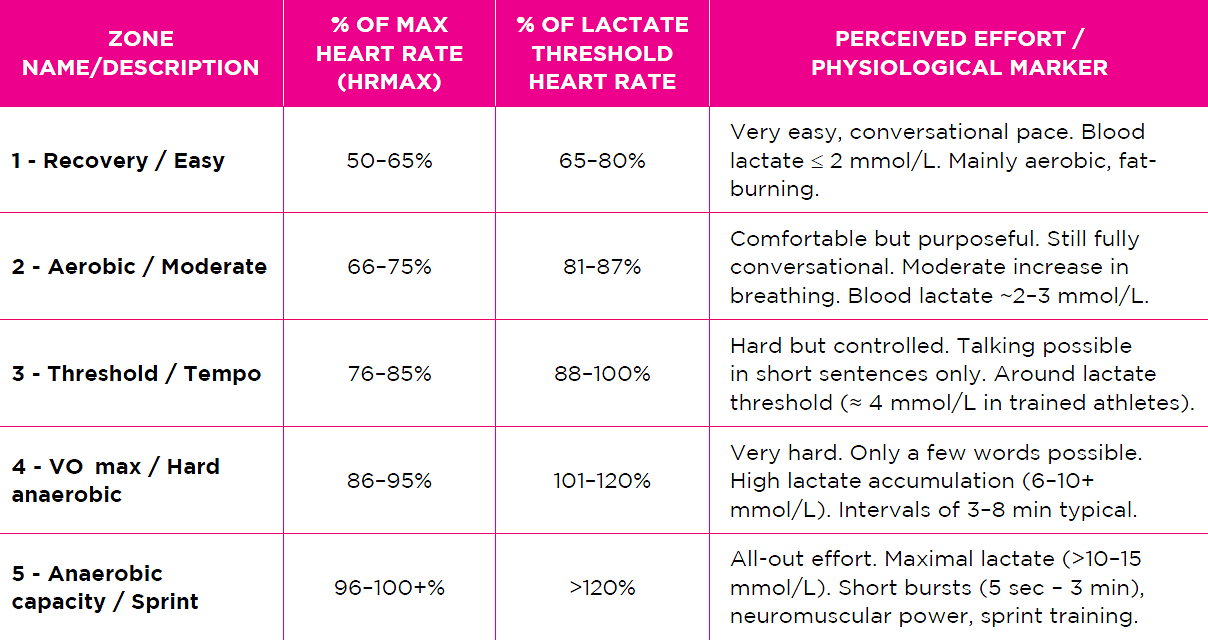

The training records that were investigated by researchers included information about training frequency, duration, training forms (endurance, strength, speed) and the intensity for endurance training sessions. All athletes used the five-zone intensity scale developed by the Norwegian Olympic Training Center (see table 1). However, for the data analysis, both the three-zone and the five-zone intensity scale were applied to enhance the clarity of findings (LIT = zone 1–2; MIT = zone 3; HIT = zone 4–5). As well as training data, the researchers also looked at the athletes’ fitness testing data accrued across the years. In total, the six athletes conducted a total of 455 physiological tests at the Norwegian Olympic Training Center; to ensure validity of the findings, only tests where the athletes were in tip-top condition (ie no illness or injury) and which were conducted in the general preparation period (August to November), were included in the analyses.

Table 1: The Norwegian Olympic 5-zone intensity scale

NB: this model is often described as a “polarized” or “pyramidal” training distribution (roughly 80% in zones 1–2, 10–15% in zone 3, 5–10% in zones 4–5). Zone 3 is deliberately narrow because Norwegian coaches believe spending too much time here (“gray zone”) gives poorer adaptations than polarizing toward zone 1–2 and zone 4–5. Lactate threshold heart rate is typically ~82–88% of HRmax in well-trained endurance athletes, which is why the percentages shift when using threshold instead of max HR.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

· There were large individual differences in the progression of training volume of the athletes (exactly as you might expect). In plain English, there was no ‘magic formula’ guaranteeing world class performance!

· However, when it came to the evolutions of the athletes’ training, there was a clear difference in the way the tier 5+ and tier 5 athletes progressed through the years and in the transition from junior to senior world-class level; specifically, the tier 5+ athletes demonstrated a gradual, stepwise increase in training volume over a much longer period compared to less consistent progression observed in the tier 5 athletes.

· This more noticeable increase in training volume in the tier 5+ athletes was primarily driven by an increase in the number of training sessions, while the duration of individual sessions only increased modestly.

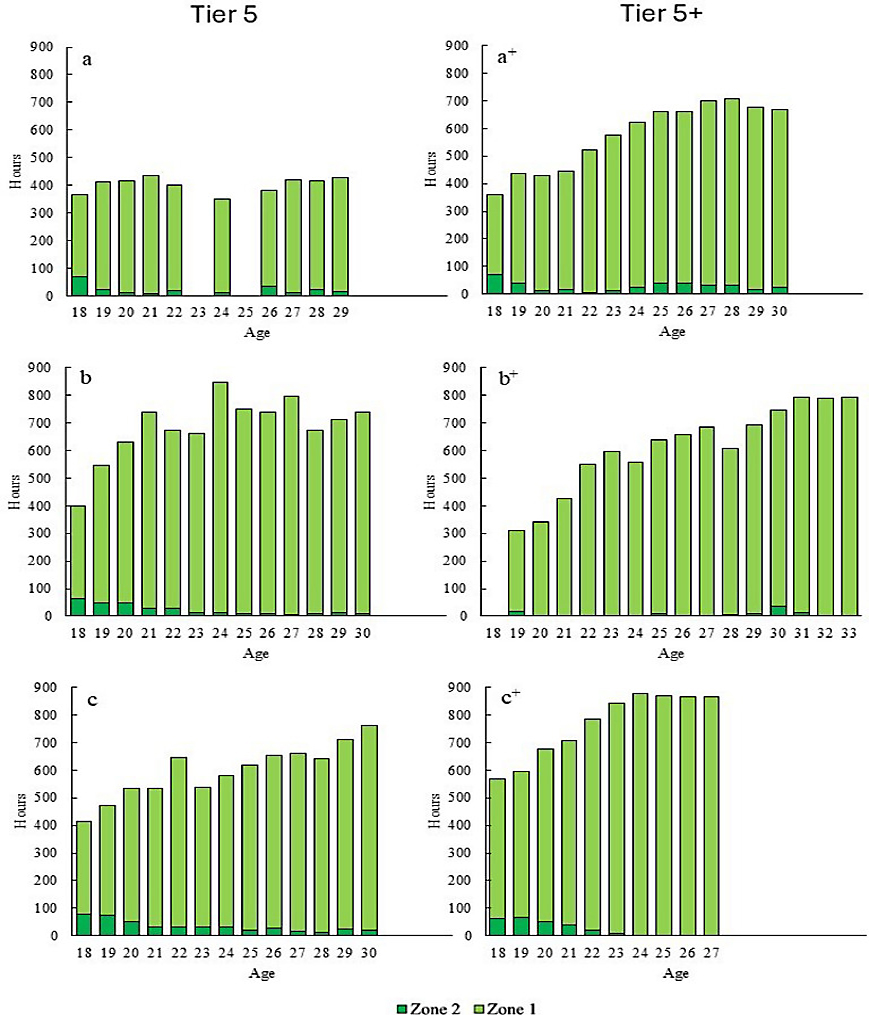

· Importantly, the increase in training volume observed in the tier 5+ athletes was primarily driven by increased volume of zone-1 low intensity training (see figure 1). There was no consistent pattern regarding the proportion or frequency of high-intensity sessions.

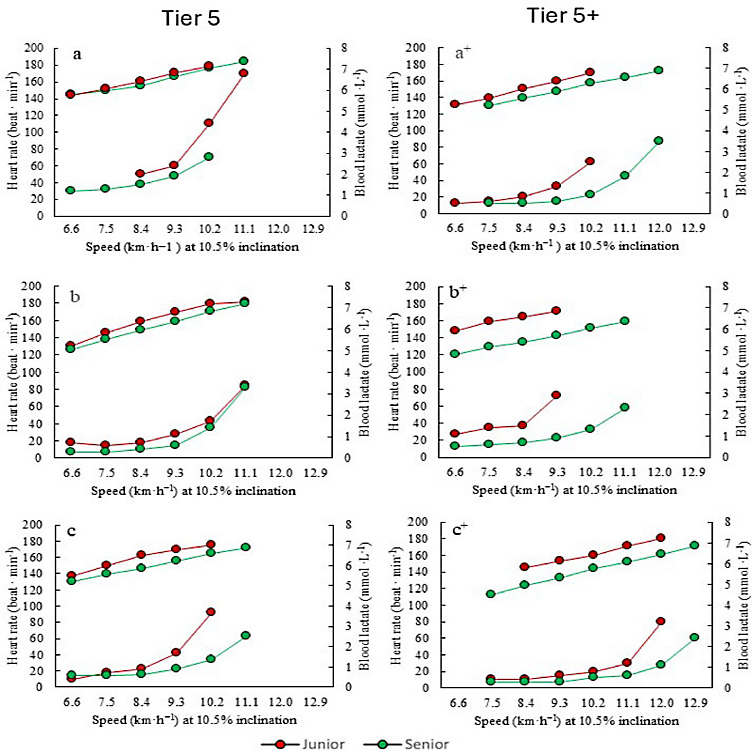

· As time progressed, the tier 5+ athletes showed larger improvements in sustainable speeds for a given level of blood lactate and heart rate than the tier 5 athletes (see figure 2). For example, the tier 5+ athletes were able to increase their average speed at lactate threshold (the point at which/lactate and fatigue begins to accumulate in the blood) by around 14% over the years compared to an increase of just 7% in the tier 5 athletes.

· The annual progression of strength and speed training was not significantly different between the tier 5 and tier 5+ athletes.

Figure 1: Annual progression of low-intensity training (LIT) for three tier 5 and three tier 5+ athletes

Light green = zone 1 training volume; dark green = zone 2 training volume. a/b/c and a+/b+/c+ represent the three periods of analysis across the three decades for the tier 5 and tier 5+ athletes respectively. Notice the more consistent increase in zone-1 training volume (light green) in the tier 5+ athletes.

Figure 2: Development of lactate threshold tests from tier 5 and 5+ athletes across three decades

a/b/c and a+/b+/c+ represent the three periods of analysis across the three decades for the tier 5 and tier 5+ athletes respectively. Red plots represent tests at junior level, green plots are the same tests at senior level. Look at the red/green lactate curves at the bottom of each graph. As they progressed, athletes moved from red to green curves. But notice how the tier 5+ athletes show a green (senior) test result much more shifted to the right compared to the red (junior) result. This shows that the as the tier 5+ athletes progressed over many years, they improved their ability to work hard before reaching lactate threshold more than did the tier 5 athletes over the same time period.

Practical implication for athletes

Very few endurance athletes reading this article will ever make it to world class level (although we’d like to think that some of the new research highlighted in SPB over recent years could help a little!). But what are the implications for recreational and amateur athletes, and can we use this info to help us develop better training plans and overall structure? The key take-home message is that gradual, sustained training evolution, focusing primarily on low-intensity training, is what counts for long-term performance gains.

For recreational and amateur endurance athletes pursuing long-term improvements, this highlights the need for sustainable, individualized strategies, emphasizing aerobic base-building rather than quick fixes or short-term interventions; amateurs should try and view their progress in the context of 5 to 10-year timescale rather than judging it over a period of a few weeks of months.

A particularly important finding in this study was that the progressive ramp-up in annual training volume in these elite XC skiers was achieved not by increasing session lengths, but rather by boosting session frequency (eg twice per day training) and prioritizing low intensity (zone-1) training for the bulk of sessions. Surprisingly, high-intensity training (zones 2 and 3) showed no clear link to elite success. For amateurs, this suggests structuring training so that around three quarters of the volume is low/easy intensity (you should be able to hold a conversation without struggling) in order to build a robust ‘aerobic engine’ without risking burnout.

Modest-duration sessions (eg 60-90 minutes) should be prioritised to minimize overuse injuries, with the number of sessions increased rather than session lengths increased to build volume. That’s not to say you should never perform long sessions in training (eg marathon preparation), but rather you should prioritize performing more sessions over longer sessions. Regular testing to check progress is also recommended; you don’t need a fancy laboratory to do this – a simple time trial test or 12-minute (running) Cooper Test can provide benchmarks to make sure you are moving in the right direction! Finally, if you are a young or junior athlete, it’s important to avoid building up to high volumes of training early on in your career. Not only will this increase your risk of burnout and injury, the evidence is that it provides no advantage in your performance as your career develops over the longer term!

References

1. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(6):1091–100

2. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12(8):1003–11

3. Sports Med. 2016;46(8):1041–58

4. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14(sup1):S383-97

5. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022;17(2):317–31

6. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015. 25(Suppl 4), 100–109

7. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17(4):437–44

8. Sport Science. 2009;13:32–53

9. Front Physiol. 2017;8:1069

10. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1288606

11. Sports Med Open. 2025 Nov 21;11:142

12. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022;17(2):317–31

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.