You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Cycling performance: long or short crank lengths for amateurs?

How does crank length affect cycling efficiency, sprinting performance and perceived effort? SPB looks at what the most recent research has to say

The past decade has seen a huge growth in the popularity of cycling, and along with it has come big strides in bike technology. Carbon fiber and super lightweight alloys based on titanium, scandium or aluminium are now de rigour in bike frame construction. Meanwhile, brake discs have replaced wheel rim braking (even on fairly budget bikes) tubeless tires are no longer considered exotic while electronic wireless gear shifting, which does away with cables, is becoming ever more common. However, the fact remains that when it come to mechanical propulsion, the principles remain largely unchanged; the cyclist applies force to the pedals, which is transmitted via the cranks to the chainring , driving the chain, which drives a cog on the rear wheel, thus producing forward motion.

Chainring design

In a previous SPB article, we looked at one aspect of the drivetrain that has been tinkered with, which is chainring design. Chainrings have traditionally used circular chain rings to drive the chain and turn the rear wheel. Despite this, some sports physiologists have questioned if the use of non-circular chain rings (containing a very slight ellipse or oval), might be better suited to the biomechanical requirements of pedalling, resulting in more force delivered to the crank for less perceived effort from the rider. The theory of non-circular chainrings is that by using a ring with its peak effective diameter when the cranks are in a horizontal position (3 o’clock and 9 o’clock), this provides a rider with maximum leverage over the crank during the power stroke, enabling the rider to develop more torque (force) or the same amount of torque but more efficiently.

The theory sounds good, but the research on non-circular chainrings is mixed at best. In a study on 12 male elite cyclists riding an incremental test to exhaustion, researchers found that during the short sprints, average power output was only slightly increased with ovalized rings, and the gains were not large enough to be considered statistically significant – ie they could have occurred simply as the result of a ‘statistical blip’(1). There were also no significant benefits in terms of blood lactate (a measured of muscle fatigue during exercise), power output, oxygen consumption or heart rate.

In another study, comparing circular and ovalized chainring use in well-trained cyclists, there did appear to be some benefits in terms of a slightly reduced level of blood lactate during high-torque efforts(2). This correlated to reduced muscle activity at the point where peak crank torque occurred during each crank rotation – supporting anecdotal observations of some cyclists that pedalling using non-circular chainrings feels easier for a given pace compared to conventional circular chainrings. A third study comparing elliptical and circular chainrings during all-out sprinting found somewhat more positive results(3); the maximal power output during each pedal stroke was significantly higher (+4.3%) when using the non-circular chainring. The researchers concluded that this improvement was likely explained by the mechanical advantage given by an elliptical ring, suggesting potential benefits on sprint cycling performance.

Leveraging the power of cranks

Overall, it’s fair to say that unless you’re a sprint cyclist, the jury is still out on the benefits or otherwise of non-circular chainrings – although for hill climbing and/or maximal effort riding, there’s slightly more evidence that they might help. However, changing the profile of the chainring is not the only way of manipulating torque output in the drivetrain. Because of the physics of levers and turning force (see box 1), a simple change to the crank length can affect torque output too.

Box 1: Levers, force and torque

Torque is a measure of the turning force that causes an object to rotate about an axis, fulcrum, or pivot. It is defined as the product of the magnitude of the force applied and the perpendicular distance from the point of application of the force to the axis of rotation, known as the lever arm. Mathematically, torque is expressed as:

Torque = F × r ×sin(θ)

(where F is the applied force, r is the length of the lever arm, and θ is the angle between the force vector and the lever arm vector).

When the force is applied perpendicularly to the lever arm – for example pushing the pedal vertically down with the cranks in the 3 and 9 o’clock position, sin(θ)=1, simplifying the equation to Torque = F × r. When understanding crank length and torque, r is the crank length in this equation, so you can see that using a longer crank increases torque while using a shorter crank decreases torque.

Standard vs. non-standard crank lengths

In years gone by, the standard crank length was 170mm, and that was pretty much the only choice offered to cyclists. However, technology and consumer choice has moved on and many manufacturers now offer a choice in crank sizes on their chainsets. For example, the latest version of SRAM’s ‘Red’ chainset now offers cyclists crank lengths of 165mm, 167.5mm, 170mm, 172.5mm, 175mm, 177.5mm! Previous research has shown mixed results on crank length. Shorter cranks (around 145–165 mm) seem to be favoured for cycling efficiency (economy) and for helping to ease knee loading(4). However, during harder efforts such as sprints or steep climbs where getting out of the saddle is required, the higher torque output generated by longer cranks (170mm and over) yields a significant performance advantage(5). This is why pro cyclists tend to favor longer cranks, as sprinting and climbing performance often play a much bigger role in determining the outcome of races!

New research

If you’re an amateur who needs to perform well on longer, flatter rides (where an efficient and comfortable cycling action is essential), but you also compete in hilly events or race over shorter distances, what crank length is likely to give you the best all-round performance? Is there a sweet spot – ie good power for sprints and hills but comfortable and efficient to avoid knee injuries or fatigue in the longer term? This is a question that a team of Chinese researchers have attempted to answer in a very recent study published in the Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness.

In this study, the researchers investigated the influence of three different crank arm lengths - 165 mm (shorter than standard), 170 mm (standard), and 175 mm(longer than standard) on sprint power, perceived fatigue and cycling economy, Cycling economy is a measure of the amount of oxygen consumed per unit of work performed/distance covered at a steady sub-maximal intensity. Economy is an important determinant of endurance performance; better economy means less oxygen consumed per mile, which means less accumulated fatigue over longer distances!

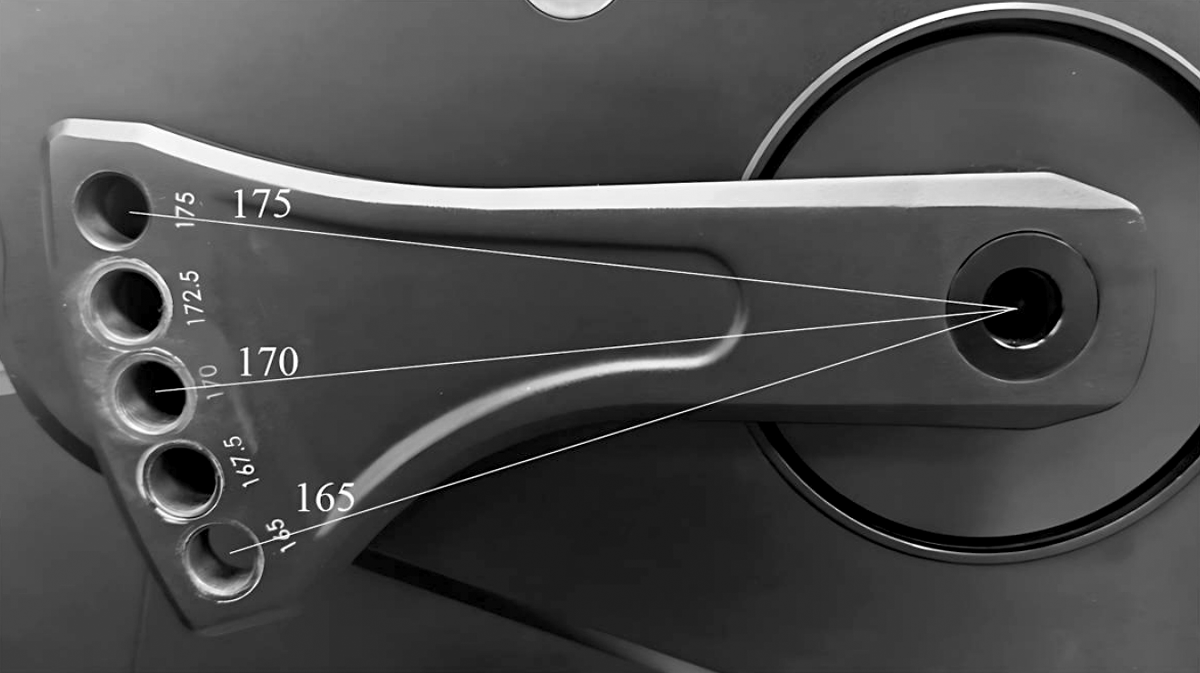

The testing was conducted using the Garmin Neo Bike Plus bicycle ergometer (see figure 1), which is specifically designed to replicate the riding posture of road cycling. A feature of this ergometer is the ability to affix pedals at different points on the crank to give different effective cranks lengths. This design allowed participants to maintain a standard cycling position throughout the trials, regardless of crank length. In conjunction with this, the GARMIN Edge 1040 bicycle computer was used to record key performance metrics, including cadence, power output, and heart rate. Together, these devices ensured accurate measurement and consistent cycling posture, closely replicating outdoor cycling conditions.

Figure 1: Crank arm of the Garmin Neo Bike Plus ergometer

How the study was run

Twenty eight fit male road cyclists were recruited, all over 25 years old with at least four years of racing experience. Participants had high levels of fitness with a maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) averaging 59mls/kg/min, and peak power at VO2max averaging 5.15 Watts per kilo of body weight – placing them firmly in the ‘elite amateur’ category. Each rider performed three separate cycling trials using the three different crank lengths. Each test was separated by 72 hours to ensure full recovery and the order of the tests (ie whether using the 165, 170 or 175mm crank lengths) was randomized. Moreover, the test were blinded as far as possible, which meant the cyclists were not told about the different crank lengths used for each trial – indeed they were told the bike set up was the same each time around. It’s true that some riders might have guessed the crank length changes from ‘feel’ of the pedalling action, but that was factored into the researchers’ conclusions. In all three tests, the saddle position, handlebar position, and fore-aft adjustments etc stayed constant, optimized for each person’s height and build.

The testing

After warming up at 100 - 150 watts for 10 minutes, riders performed an incremental ramp test, increasing by 25 watts every two minutes until exhaustion. Exhaustion was determined as the point heart rate reached 90% of maximum, the perceived effort reached nine on the 1-10 scale, oxygen use plateaued, or cadence could no longer be sustained at 80+rpm. Testing was also carried out for cycling economy, measuring oxygen consumption at 60% of VO2max (moderate intensity). In the sprint tests, there was a 10-minute warm-up, and then a five-minute pause. Following this, the cyclists were asked to perform a 6-second all-out seated sprint, during which the Garmin captured peak power for the sprint, average power, average cadence and peak cadence. The cyclists repeated these same tests using each crank length and the results were compared.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

· Sprint performance – there were no significant effects of crank length on peak or average 6-second sprint power. The researchers hypothesized that while crank length influences pedaling mechanics and efficiency, its impact on overall performance is limited when only crank length is altered. Longer cranks may provide greater leverage but they also require larger pedalling circles and greater propulsion force, which negates any increases in power unless the cyclist is very highly trained (ie pro level).

· Cycling economy - different crank lengths did not have a significant impact on cycling economy during submaximal cycling in these well-trained cyclists. While altering the crank length alters torque, it seems that the minor changes in knee and hip joint range of motion resulting were insufficient to influence overall efficiency, and that cycling economy is likely more closely related to cadence, rider experience, pedaling technique. In novice cyclists, using shorter cranks during submaximal cycling HAS been shown to improve power output and cycling economy(6). However, professional cyclists can quickly adapt to changes in cadence and power output associated with different crank lengths, maintaining stable heart rate performance. Since the participants in this study were high-level amateur cyclists, whose weekly training volume was not too dissimilar to that of professional cyclists, the changes in crank length may not have caused significant variations in cardiovascular system responses and cycling economy.

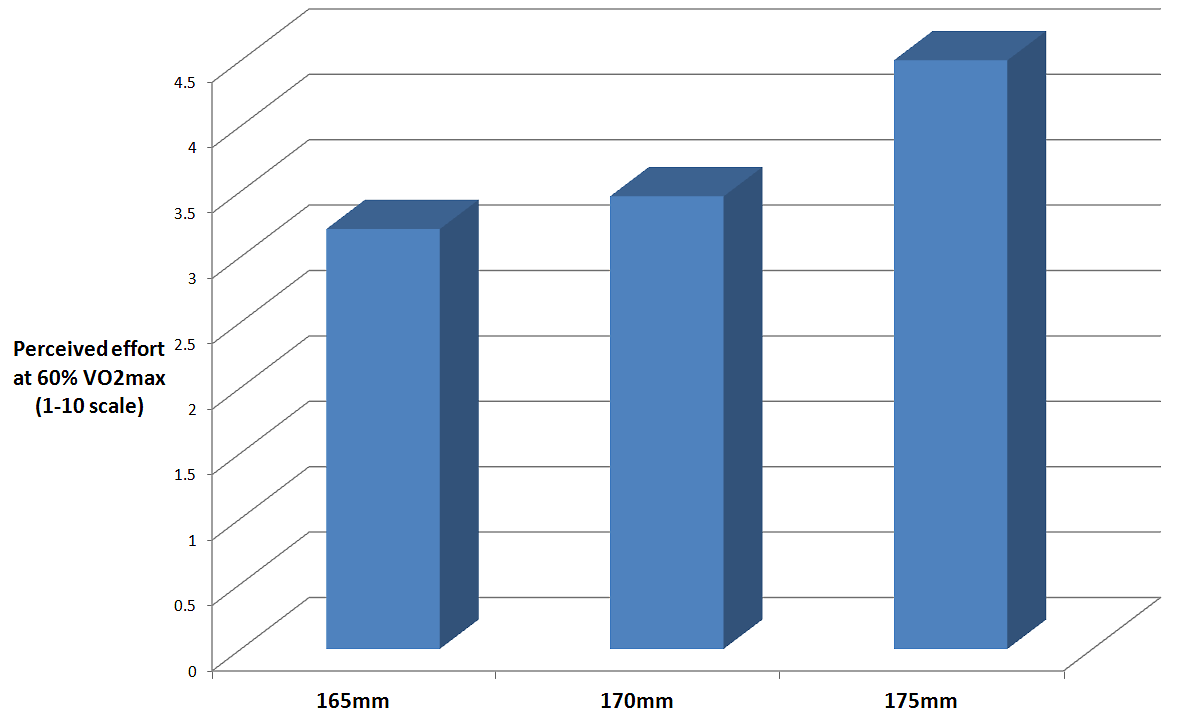

· Perceived effort – the shorter crank lengths (165 mm and 170 mm) significantly reduced perceived fatigue compared to longer cranks (175 mm) – most likely due to reduced joint movement and loading during high-cadence cycling (see figure 2)(7). While longer cranks provide better leverage for power output at high intensities, the increased muscular load on the knee and hip joints leads to higher fatigue(8). Despite the relatively extensive experience and training backgrounds of these high-level amateur road cyclists, they likely still struggled to fully adapt to the additional muscular demands imposed by the longer cranks, resulting in higher subjective fatigue.

Figure 2: Crank length and perceived effort at 60% VO2max

Conclusion and recommendations for cyclists

What is the take-home message from this research? Unlike some studies, the conclusion here is fairly clear cut. While professional cyclists may derived additional benefits from a 175mm crank length, if you’re an amateur cyclist - even if you’re highly trained amateur – you are likely better off using a 165 mm or 170 mm crank. Not only do these shorter lengths reduce subjective fatigue compared to a 175 mm crank, there are no downsides regarding cycling efficiency or sprint/hill-climbing performance. For novices or those who engage mainly in non-competitive recreational cycling, 165mm cranks may be the best choice of the lot. Not only is this crank length likely to produce the lowest amount of subjective fatigue and injury risk, cycling economy can be improved with no detriment to sprint performance. However, for the most highly trained cyclists competing at or near pro level, the highly trained musculature means that 175mm cranks can deliver torque benefits for sprinting and climbing power, without affecting perceived effort or cycling economy!

References

1. J Sports Sci Med. 2014 May 1;13(2):410-6

2. J Physiol Anthropol. 2009 Nov;28(6):261-7

3. J Sports Sci Med. 2016 May 23;15(2):223-8

4. Int J Exerc Sci. 2021 Sep 1;14(1):1123-1137

5. J Sports Sci. 2022 Jan;40(2):185-194

6. J Sports Sci. 2017;35(14):1328–1335

7. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(4):705

8. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(9):1689–1697

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.