You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Older athletes: resist the aging process!

SPB looks at the new research on the remarkable long-term anti-aging benefits of resistance training, and explains which training type works best for athletes

A famous 1970s American auto racer and stuntwoman called Kitty O’Neil Collins – nicknamed ‘the fastest woman in the world’ – was once asked about the impact of aging on her ability to perform stunts. She replied pithily that “Aging seems to be the only available way to live a long life!” She was right of course, and understood that the inevitable process of aging is something that all athletes have to come to terms with as the years tick by.

The impact of aging on performance

There are a number of physiological changes that take place as we age, and while lifelong top-quality nutrition and exercise can dramatically slow these changes, as each decade passes, maximum performance potential declines (for a more detailed discussion on aging and performance, readers are directed to this article). Although there are large individual variations, as a rule of thumb, peak performance is typically attained around 25-30 years of age, after which athletes will experience a steady decline in maximal exercise capacity, no matter how long or intensely they train.

The reason for this decline is primarily due to a combination of reduced muscle mass combined with decreased cardio-respiratory (heart-lung) function. We know this to be the case because over the years, numerous studies have shown the following(1-4):

*Strength and speed tend to peak at the earlier end of this age range while endurance peaks in the later range.

*During early middle age (40 to 50 years of age), physical activity declines resulting in a typical 5-10kg of body fat gain. Moreover, this decline continues into old age.

*Maximum heart rate also declines with age and (partly because of this fact) maximum aerobic capacity also declines by about 1% per year (although this decline may be stemmed with regular training).

*The mass of fast-twitch muscle fibres (needed to produce strength and power during high-intensity exercise) is most pronounced during the 30s, where studies have shown a decline in power of 3% per annum with 1% per annum every year thereafter for both men and women.

Muscle mass and aging

One of the most striking age-related changes that take place as the years tick by is a steady loss in muscle mass and muscle fiber function, particularly after middle age. In sedentary older adults, the decrements in the amount of skeletal muscle (and therefore strength to perform day-to-day tasks) may be large enough to compromise independence and quality of life(5). But age-related muscle mass loss isn’t the only problem; research shows that in the muscle fibers that remain as we get older, function tends to reduce – ie the contractile force generated per fiber tends to decline with age.

This functional loss in muscle fibres is thought to be partly or even largely explained by a process called ‘muscle fiber denervation’(6). Muscle fiber denervation seems to occur either through the breakdown of the neuromuscular junctions, reducing the ability of electrical signals to stimulate muscle contractions, or through the death or muscle motor neurons or both. Interestingly, it seems that regular pulses of electrical signals passing through the motor neurons and muscle fibers (ie vigorous exercise) is required for maximal preservation of neuromuscular function as we age. Indeed, inactivity is not merely an innocent bystander, but plays an active role in denervation by increasing the production of chemicals and hormones that are hostile to the ability of neurons to survive the aging process(7). This really is a case of ‘use it or lose it’!

Combating muscle mass and muscle function loss

The importance of minimizing muscle mass losses as we age cannot be overstated – not only for athletic performance but also health. Given this importance, how can older athletes deal themselves the best physiological hand possible to preserve maximum muscle mass? The answer of course is good nutrition and (as implied above) the continuance of vigorous exercise into older age.

Regarding nutrition, a number of studies have concluded that as we age, consuming enough protein to preserve muscle mass becomes more important than ever. For example, a recent review study surveyed the recent research on nutrition, muscle mass and aging, and concluded that older adults (whether athletes or not) should increase their intake of protein above the recommended dietary allowance (ie consume more than the 0.8 grams per kilo of bodyweight that is commonly cited)(8). It also concluded that a special effort should be made to increase the intake of omega-3 essential oils (EPA/DHA – found in oily fish such as salmon, herring, mackerel, sardines, trout etc). In particular, it seems that a combination of adequate protein and omega-3 intakes stimulates muscle synthesis by boosting an important signalling molecule called ‘mTORC1’, which has the ability to upregulate gene activity associated with muscle growth (see this article).

What kind of protein and omega-3 intakes should older adults be aiming for? Observational studies suggest protein intakes from ranging from 1.0 to 1.6 gram per kilo of bodyweight per day can promote greater muscle strength and function, with those who are physically activity tending towards the upper end of this range(9). Interestingly, these same studies also favor animal protein sources over plant sources. Regarding optimum omega-3 intakes, studies where older or elderly people (both sedentary and active) were supplemented with a total of 3000mg per day of DHA/EPA and where the EPA intake in that combination was 800mg per day or more, have shown positive effects on strength and muscle mass(10,11). Where consuming plenty of fatty fish (2 or 3 days per week) is not an option, omega-3 supplementation should be considered as an essential part of optimum nutrition for those of advancing years!

The heavy weights option

When it comes to exercise and muscle mass preservation in later years, you will not be surprised to learn that strength training is vital. What’s more, studies show that vigorous strength training using relatively heavy resistance is essential, and much better than cardiovascular training alone or gentle/moderate-intensity resistance training (as used to be thought)(12). Instead, the optimum scenario involves a combination of cardiovascular training and heavy strength training. And just as the case in younger athletes, older athletes (and their sedentary counterparts) need to adhere to the basic strength-training principles when trying to build or maintain muscle mass(13):

· The training load applied needs to overcome habitual levels of strength – ie the muscles need to be pushed or overloaded to generate a training adaptation.

· Training needs to be specific and adapted to the individual – ie to build leg muscle/strength, you need to train the legs and set a program that is appropriate for the individual’s current level of fitness.

· Training loads (intensity, volume) need to be adjusted/increased over time (while allow periods of recovery) in order to continue to provide a growth stimulus as muscles adapt.

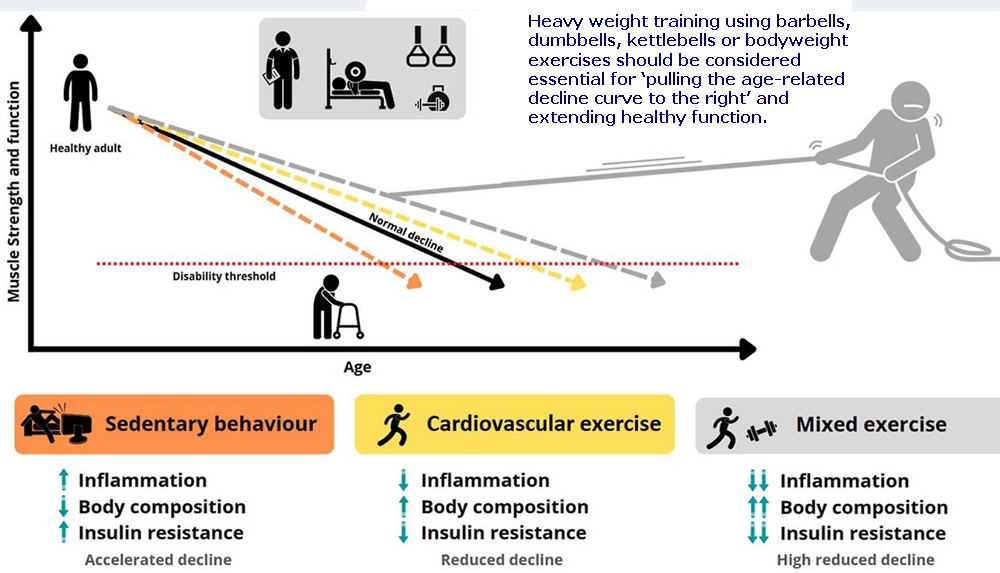

In a comprehensive review study on this topic, researchers likened the use of heavy strength training as a way to make the slope of age-related decline more shallow, therefore prolonging mobility and health well into old age (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Optimum training approach to slow muscle mass loss and maintain health*

Long-lasting benefits

One of the fundamental physiological principles of fitness training is ‘reversibility’ – ie that once training pauses or ceases, those hard won gains in training begin to dissipate and fitness declines. Over lengthy period of time with no further training stimulus, fitness levels may end up right back down to square one (see this article on detraining)! The good news for older athletes who engage in strength training is that while significant strength gains can be had in a relatively short time period, strength losses seem to occur fairly slowly when training is paused.

For example, a study on 53 older adults had them perform resistance training for 24 weeks at the end of which strength and muscle mass gains were recorded(14). They were then reassessed one year later to see how those strength gains had declined. After no resistance training for a year, both muscle mass and strength declined. When looking at the cross-sectional area of the quadriceps (a measure of thigh muscle mass), it declined by around 580mm2 in those who had been completely sedentary during the previous 12 months but by only by around 310mm2 in those who had performed some kind of activity in the intervening 12 months. However, even in those who had ceased exercise completely, much of the initial gain in cross-sectional area (around 1300mm2) had been retained.

Longer-lasting benefits

The findings above suggest that when strength training is ceased, the accumulated benefits of that training are only partially reduced after a year. However, other studies have shown even longer-lasting benefits for a period of strength training. In a study by Greek researchers, scientists compared the long-term effects of an initial 24-week strength program at conducted at either low (55% 1-rep max) or high (82% 1-rep max) intensity in healthy 70-year olds(15). At the end of the 24 weeks, the low-intensity training improved their strength by 42-66%, anaerobic power by 10%, and mobility by 5-7%. Meanwhile, the high intensity training elicited even greater gains - 63-91% in strength, 17-25% in anaerobic power and 9-14% in mobility. The real eye opener however came when the men were retested eight months after ceasing strength training entirely; all the training-induced gains in the low-intensity group had had disappeared after four to eight months of detraining However, in the high-intensity group, all of the strength and mobility gains from the initial 24-week program remained, even after eight months of detraining!

This differentiation between low and high-intensity training for retaining strength and muscle mass gains was also reflected in a large-scale study known as the Live Active Successful Ageing (LISA) study(16). This study looked at 451 healthy older men and women (aged 62-70) who trained for 12 months using either heavy-intensity or moderate intensity resistance training. The heavy-resistance group performed a supervised full body program three times per week at a commercial gym using machines, with sessions consisting of three sets of 6–12 reps at 70%–85% of 1-rep max. The moderate-intensity group carried out circuit training using bodyweight and resistance bands once per week in a supervised setting and twice per week at home. Progression was ensured by increasing the loading of the resistance bands. When they were retested a year later, only the heavy-intensity trainers retained muscle strength (even if they had become completely inactive).

Very long-lasting benefits!

Training using heavy resistance for one year and getting two year’s increased leg strength seems like a win-win, particularly given the sports performance benefits that accrue from increased strength. However, in the study above, the researchers didn’t just pack up and go home after the 1-year follow up. The researchers kept in touch with the study participants with a view to a further retest at a later date to see if there were even longer-term benefits from heavy strength training. This is exactly what happened after another two years – ie a whole three years after the participants had ceased strength training – with the results just published in the ‘British Medical Journal (BMJ) Open Sport and Exercise Medicine’(17).

At year #4 after the start of the study (ie three years after the initial period of resistance training), 369 participants attended follow-up assessments - 128 from the high-intensity group, 126 from the medium-intensity group and 115 from the control group. This meant that 82 of the original participants had dropped out. However, an analysis by the researchers showed that those who had dropped out were no different in terms of in the benefits they had gained at the 1-year follow up. In plain English, the 369 participants who were measured in this 3-year follow up were no fitter, stronger or healthier at the 1-year follow up than those who had dropped out.

What they found

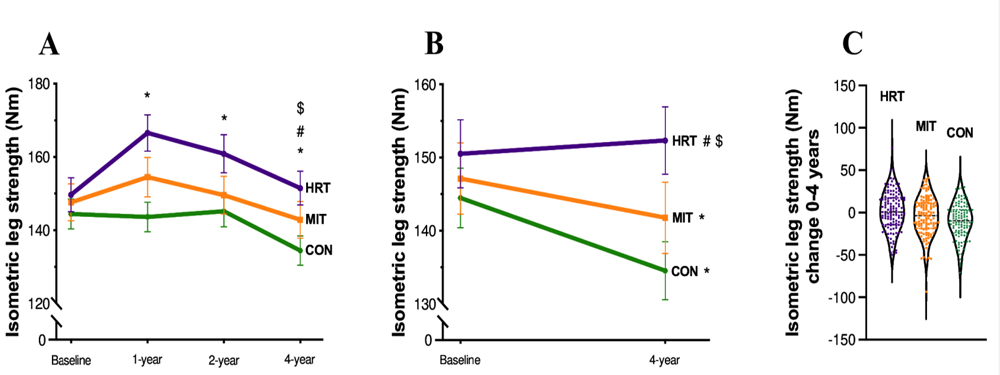

When the 369 men and women were retested three years after ceasing their strength program and results were analyzed, the resulted amazed the researchers. Both the control group (as expected) and the medium-intensity had lost strength compared to the start of the study. However the heavy-intensity resistance trainers had retained sufficient strength so that strength levels were still higher than they were at the start of the study (baseline) (see figure 2). In other words, three years after ceasing their heavy strength training completely, they were still stronger in their lower body than they were four years previously!

Figure 2: Changes in leg strength three years after ceasing training

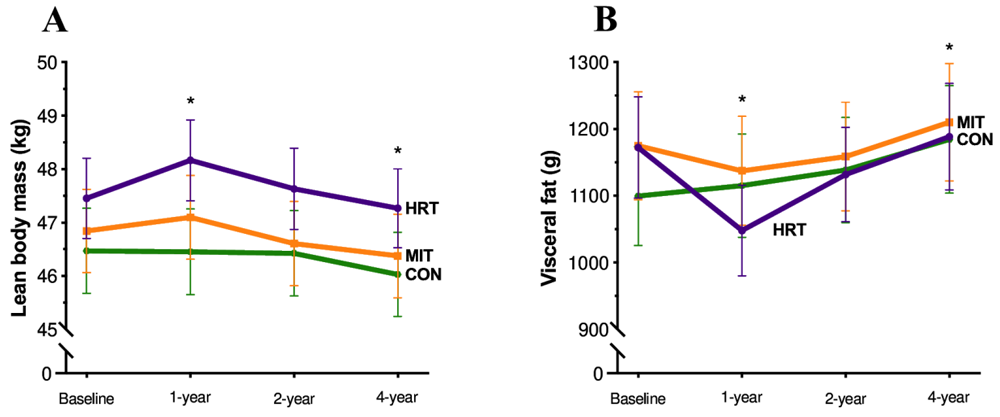

When it came to body composition changes, while all three groups had gained visceral fat (also known as belly fat or active fat that surrounds internal organs in the abdominal cavity) after three years of ceasing training (again, as expected), the heavy-intensity resistance group had retained enough lean muscle mass so that their overall muscle mass was no different to that at the start of the study four years previously (see figure 3). By contrast, both the moderate-intensity and control groups had lost lean muscle mass compared to the study start – exactly as expected when considering age-related changes in muscle mass. In summary, training using heavy-resistance had conferred no less than four years’ protection against the usual age-related lean muscle mass losses!

Figure 3: Lean muscle mass and visceral fat changes

A = lean body mass changes. B = visceral fat changes. Only the heavy-resistance training group retained all their lean body mass compared to baseline. Note also that while visceral fat levels were similar across groups three years after ceasing training, only the heavy-resistance group significantly had decreased their levels of body fat after one year.

In summary

The conclusions and recommendations that follow from recent findings on strength training in older athletes (and other older adults) are clear and simple. If it’s longevity and/or performance you want to achieve, the inclusion of regular heavy resistance training should be considered as a must – not as an optional extra. The more recent data suggests (encouragingly) that the physiological, health and performance benefits from heavy resistance training extend well beyond any period of training.

This means that athletes and other are likely to reap big rewards from periods of heavy resistance training, interspersed with periods where no resistance training is carried out – ie it seems that the continual practice of resistance training without taking breaks is not needed. That’s good news because older athletes engaged in other form of training or competition can plan their resistance training to fit in with these demands (eg cease resistance training in the run up to an event) yet still benefit from performance gains.

Paying attention to nutrition is important too. Contrary to the conventional advice, older athletes are likely to need more protein as they age, not less – as much as 1.6 grams per kilo of bodyweight per day during periods of more intense training. In addition, they should ensure a plentiful intake of omega-3 essential fat in the diet. If fatty fish is not to your taste or just difficult to get hold of, supplementation to ensure around 3 grams per day is recommended!

References

1. Sports Medicine 2003; 33(12):877-888

2. Phys. Sportsmed 1990; 18:73

3. J. Appl Physiol 1987; 62:625

4. American J. of Ortho 2002; 31(2):93-98

5. J Physiol. 2022 Dec;600(23):5005-5026

6. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021 Aug 1;321(2):C317-C329

7. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021 Aug 1;321(2):C317-C329

8. Nutr Rev. 2024 Feb 12;82(3):389-406

9. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023 Jun 16;78(Suppl 1):67-72

10. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;102:115–122

11. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144828

12. Front Sports Act Living. 2022; 4: 950949

13. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18. 10.3390/ijerph18010103

14. Exp Gerontol. 2019 Jul 1:121:71-78

15. Br J Sports Med. 2005 Oct;39(10):776-80. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.019117

16. Exp Gerontol. 2020 Oct 1:139:111049

17. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2024;10:e001899

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.