You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength training: why calves matter for athletes

SPB looks at the relationship between calf strength and athletic performance, and investigates new research on the best way to improve that strength

Unless you’ve had a calf-sprain injury or suffered from Achilles tendonitis, the chances are you haven’t thought much about the role of calf muscle strength and endurance for athletic performance. This is perhaps not surprising as the calf muscle fibers are predominately ‘type-1’ fibres, and so naturally tend to have high levels of endurance, which means they are less likely to fatigue during exercise compared to many other muscle groups(1). For most athletes therefore, even those who undertake regular lower-body strength training, calf exercises tend to take a back seat at the end of the workout, or are not trained at all.

Calf strength/endurance matters

Although often neglected by athletes, calf strength and endurance really does matter to performance. For example, a study on 100-mile ultramarathoners concluded that calf muscle cramping in the later stages of a race was not associated with dehydration or electrolyte losses as is commonly believed - but rather due to a relative lack of strength and endurance in the calf muscles when tasked with such a long event(2). Meanwhile, studies on field sport players such as rugby players have found a very large and significant association between calf muscle strength/endurance and sprinting and acceleration ability(3), which is a critical metric for overall performance in a competitive match.

In a 2022 study researchers investigated whether, and if so how, key anatomical metrics of the calf muscles were related to athletic performance(4). They found that greater muscle thickness (size) and length of the gastrocnemius muscle (see figure 1) were strongly correlated to the ability to generate power and execute high-intensity (anaerobic) tasks such as sprints and accelerations. They concluded therefore that these metrics can be used as a predictor of athletic ability. In another study, researchers investigated the correlation of the 1-rep max (1RM – the highest load that can be lifted for one full rep) in the calf raise exercise and sprint performance up to 30 meters(5). The results showed strong and very significant correlations in calf strength and sprint performance. This led the researchers to conclude that the dynamic maximum strength of the calves is a basic prerequisite for sprint performance and should be regarded as a key performance parameter.

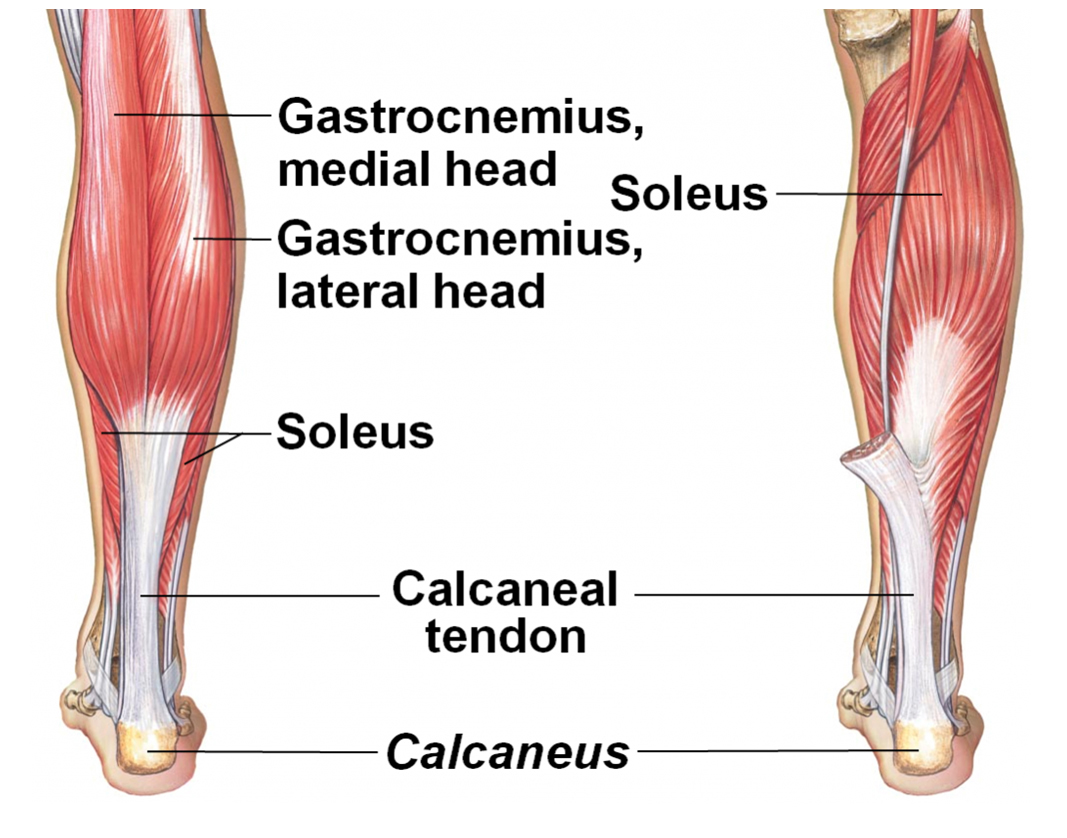

Figure 1: Anatomy of the calf muscles

On the left image, the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius muscle is shown with the soleus muscle lying underneath. The right image shows the soleus muscle with the gastrocnemius muscle cut away for clarity. Although both muscles are used during the drive phase of propelling the foot off the ground when running or sprinting, the gastrocnemius is more involved where the leg is not bent or bent only slightly (at the knee), whereas the soleus muscle becomes more heavily involved the more the leg is bent during that drive phase.

Training the calf muscles

As we’ve seen above, there’s a powerful argument for athletes whose sports involve running or jumping to strength train the calf muscles in order to achieve high levels of performance. However, due to their high content of endurance ‘type-1’ fibers, muscles like gastrocnemius and soleus are notoriously stubborn to strengthen because they’re used constantly in daily activities like walking, making them resistant to hypertrophy (muscle growth)(6).

Although strength-training routines for calf muscles vary, they typically involve frequent training (at least two or three times per week) with enough sets (often multiple sets per session) to stimulate growth(7). One reason for the use of multiple sets is so that heavy (6–12 reps) and lighter (15–30 reps) loads can be mixed in order to target both the type-1 (slow twitch) and type-2 (fast twitch) fibers in the calves. For athletes who need to invest the bulk of their time and effort training for their main sport, spending a lot of additional time and effort performing multiple sets of calf training can be an onerous demand. Hardly surprising then that many athletes just skip calf training, or add a couple of token sets into a strength workout.

A partial solution

One strength-training technique that is sometimes used to train stubborn muscles is ‘partial reps’. A partial rep is where an exercise is performed through a limited range of motion rather than the full range. Using the calves as an example, during the standing calf raise machine exercise (to train the gastrocnemius) the goal for full range of motion is to lower the heels smoothly down towards the ground until a strong stretch is felt in the calves/Achilles, and then rise the heels as high as possible without using a jerky or ballistic action [see the video below]. In a partial rep, only a portion of the range of motion is performed – eg heels stretched down and below the balls of the feet then halfway up to a parallel heel elevation.

Partial reps are often combined with a full range set of reps – for example, partial reps performed immediately before a full range set commences (initial partials) or some partial reps immediately after a full-range set has been completed (post-failure partials). Because a partial range rep is easier to complete than a full-range rep, the rationale for their use is as an additional stimulus – in other words as a technique for driving a muscle into a deeper state of exhaustion. This creates a greater strength and growth stimulus, but without same degree of training load/stress that would occur if only full-range reps were used to create that amount of degree of exhaustion.

A typical calf training routine combining partials with full range reps might look like this:

· Exercise - standing or seated calf raises (using a machine, dumbbells, or body weight).

· Phase 1 - Initial partials: 10-15 partial reps from the lowest (heel stretched) position, moving upwards through only a quarter or half of the full range of motion, focusing on controlled movements to maximize tension in the calves.

· Phase 2 - Full range of motion reps: immediately performing 10-15 full range-of-motion reps in the same set, going from a deep stretch to a full contraction (on toes).

In post-failure partials, phases 1 and 2 above are reversed.

In these routines, 3+ sets are performed with 60–90 seconds of rest between sets. The weight is selected so that the reps are only just possible (a higher loading is needed for partials). This routine can also include a variation where sets of standing calf raises (targeting gastrocnemius) and seated calf raises (targeting soleus) are alternated in order to hit both major calf muscles. The theory behind partial reps (in particular initial partial reps) is that they can exhaust the calves early, making full range of motion reps more challenging even with lighter weights, which can stimulate growth. Also, they can increase the time under tension – ie the muscle is working – which is a key driver of hypertrophy(8). And when performing partials in the stretched position, they can strengthen connective tissues. This in turn can reduce strain during explosive movements like sprinting or jumping.

Do partials work for calves?

The theory on partial reps is great, but does this approach yield superior results? It turns out fairly recent research looked at all the data on this topic(9). The researchers compared training the calves with full range of motion reps (ie ‘normal’ reps) only and using partial reps only. They found that full range of motion reps produced superior results, albeit not by a great margin. However, when an analysis of training using partial reps only was carried out, the gains in calf muscle growth appeared to be larger than that with full range reps, (even though full-range training seemed to produced the greatest strength gains). The partial rep theory seems to be valid for muscle growth therefore, but the next question is whether initial partial reps or post-fatigue partials are better for promoting calf growth?

The good news is that a new study by a team of Norwegian scientists provides clarity about how best to use partial reps to build calf strength(10). Published in the European Journal of Sports Science, this research compared calf training with initial partial repetitions versus full range-of-motion (ROM) repetitions followed by past-failure partials on gastrocnemius hypertrophy. In the study, 23 participants (16 men and 7 women) were recruited, all of whom met the following criteria:

· Resistance trained, defined as having performed at least two resistance sessions a week for the last three years prior to the start of the intervention.

· No previous self-reported use of anabolic steroids or other muscle-enhancing illegal agents.

· No injury or illness that could compromise the results or participation of the study.

What they did

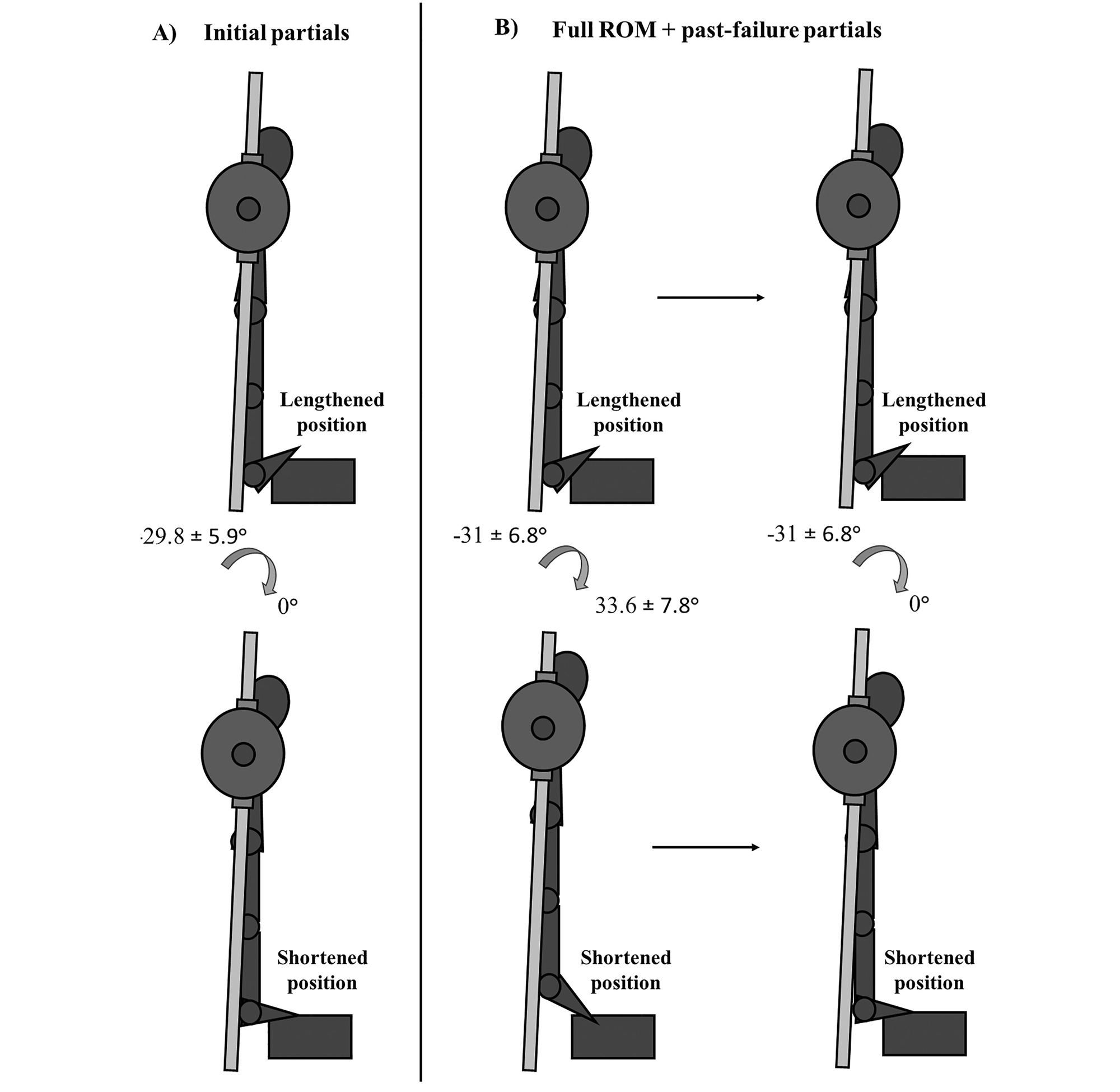

The participants trained their calf muscles to momentary failure twice per week for eight weeks using calf raises on a Smith machine. However, the nifty aspect of design was that each participant trained his/her left and right legs separately, with either the left or right leg randomly allocated to one of two conditions:

· Partial reps performed in the extended position (from a heel position of 30 degrees below horizontal to horizontal – see figure 2).

· Full range of motion reps, with additional partial reps (in the same range described above) added at the end of the set.

This design allowed each participant to act as his/her own control, which helps to eliminate inter-subject variability (a significant source of error). There were two training sessions per week, and in each session, each limb was trained with four sets of initial partials, or full range + post-fatigue partials. Therefore each leg was subjected to eight sets per week. The repetition range was set at 10-20 reps for the initial partials and 5-10 reps full range + 5-10 reps post-fatigue partials to ensure similar repetition volumes across conditions. Before and after the 8-week intervention, calf muscle thicknesses (medial gastrocnemius) were assessed using B-mode ultrasonography, which is known to be a highly valid and reliable method for tracking changes in muscle size over time(11). The muscle growth results obtained for each leg were then compared using a statistical technique known as ‘Bayesian analysis’, which is a good tool for spotting significant trends in studies where the number of participants is relatively small.

Figure 2: Training protocol for the left and right legs of each participant

What they found

The key finding to emerge from the before/after measurements of calf (gastrocnemius) muscle growth were as follows:

· Both the initial partials and the full range plus post-fatigue partials produced very significant gains in calf muscle size (and therefore mass).

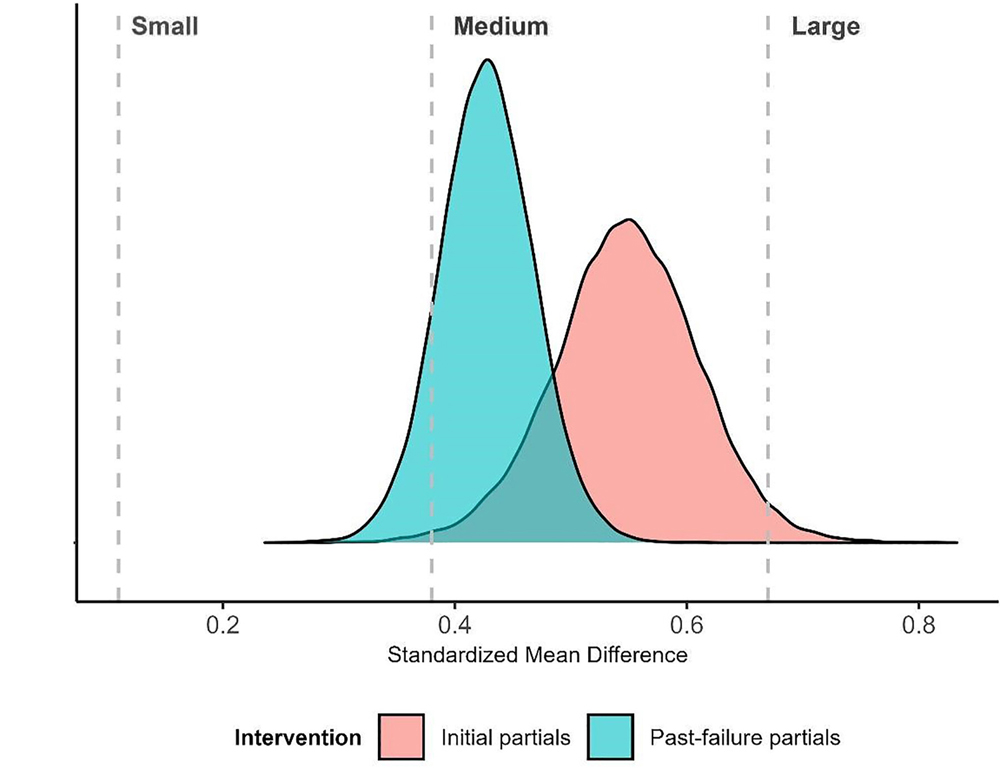

· When the two training methods were compared, it was the initial partials that appeared to produce the best gains (a 9.5% gain in gastrocnemius size compared to 6.7% in the full range plus post-failure partials) – see figure 3.

· The training loading used during the 8-week program progressed in both the training conditions (as the calf muscles adapted to the program). However, more progress was seen in the initial partials condition, suggesting slightly greater strength adaptations.

Figure 3: Bayesian distribution plot for effect size in the two training conditions

Summary and practical implications

The first thing to say about these findings is that both these training methods produced great gains in calf size (which implies greater strength also) with just four sets of exercise performed twice per week. For athletes who are short of time, this is encouraging news; combining normal full range reps with partials or performing only initial partials appears to be significantly more effective at building calf muscle mass than ordinary full-range reps alone. Overall, the initial partials method showed slightly better results than full range plus post-fatigue partials. However, the difference between the two wasn’t huge and there’s still a possibility that the extra growth benefits produced by the initial partials could have been a statistical ‘blip’. In plain English, this means that both approaches work, but training using initial partial reps might give you a slight edge for calf growth. By contrast, as mentioned above(9), including some full range of motion sets might be better in terms of absolute strength gains.

It’s worth noting that this study used experienced resistance trained participants; if you’re a novice to strength training or you already weight train but routinely neglect to train the calves, you might want to consider a few weeks of more conventional calf strength training (eg 3 x 15-20 reps performed to fatigue) before launching into partial rep routines to failure. It also should be pointed out that the training program in the study above targeted the medial gastrocnemius using standing calf raises, but you can also apply the same training principles to the seated calf raise in order to target the soleus (the other main calf muscle – see the video below):

Regardless of which training method you use to strengthen your calves, here are some general training tips:

· Focus on slow, movements to feel the burn in your calves, and don’t rush.

· If you try an initial partials routine, start your calf raises with 10–15 partial reps in the stretched position (heels low) moving only partway up.

· If you try post-failure partials, ensure that your first full range reps really are full range, and that you perform them smoothly.

· Aim for four sets per session and two sessions per week.

· Use a loading that allows (just) 10-15 reps per set. As you switch between full range and partials, you will likely need to adjust the loading. The same is true as your calf muscles become stronger over the following weeks!

References

1. Physiol Rep. 2020 Apr 27;8(9):e14427

2. Sports Med Open. 2015;1(1):24

3. Clin Anat. 2022 Jul;35(5):544-549

4. Clin Anat. 2022 Jul;35(5):544-549

5. Res Sports Med. 2018 Oct-Dec;26(4):474-481

6. Physiol Rep. 2020 May;8(9):e14427

7. Research in Sports Medicine 2018. 26(1), 1–8

8. Journal of Applied Physiology 2019. 126, no. 1: 30–43

9. International Journal of Strength and Conditioning 2023. (3) no. 1. doi.org/10.47206/ijsc.v3i1.182

10. Eur J Sport Sci. 2025 Sep;25(9):e70030. doi: 10.1002/ejsc.70030

11. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2004. 91, no. 1: 116–118

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.