You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Turn up the heat: new thinking on effective warm ups

Does a warm up have to be active or dynamic in order to be effective? SPB looks at new and rather surprising new research

All athletes know (or should know!) that warming up before vigorous training sessions or competition is important. When you’re training hard or competing, you can be burning up to 20 times more energy than you use at rest, and without some kind of preparation for this intense work, your muscles and joints can be put under quite a bit of physiological stress. This is because muscles that are cold are also more inelastic, increasing the amount of internal friction (and effort) required for muscle movement. Cold muscles also lack an optimum flow of oxygenated blood, which leads to higher concentrations of muscle-fatiguing lactate if you work them hard without first warming them up. Not only that, but the joints involved in producing movement are stiffer and require more effort to move through their natural range of movement when they’re cold making the ligaments supporting these cold joints more prone to damage or tears. So, if you simply tear off at full speed without any warm up, it’ll not only blunt your performance, you’ll also be increasing your injury risk into the bargain.

Changing warm ups

Until the early 2000s, most sport science and PE textbooks were agreed on what constituted the perfect pre-exercise warm up:

- A gentle to moderate aerobic pulse raiser to send oxygenated blood (and extra heat) to the working muscles.

- Mobilization work to loosen the joints.

- Some pre-exercise stretches to prepare the muscles for the larger range and velocities of movements they would encounter during exercise.

However, more recent research has suggested that a more active and dynamic warm up may be preferred because a period of pre-exercise stretching not only allows the heat generated in muscles to dissipate, but can potentially result in potentially resulting in worse performance than no warm up at all (see this article by Dr Gary O’Donovan)(1,2). For this reason, warm-ups that are purely active in nature, and which contain dynamic stretches rather than static (passive stretches) are now routinely recommended across a wide range of sports such as soccer and rugby, where high-intensity efforts are often required from the get go(3).

New research

While a more active and dynamic approach to warming up seems logical, and is widely accepted, is this approach to warming up always better? Are warm ups that involve passive stretches always inferior to dynamic warm ups? And can completely passive warming strategies such as saunas, warm baths, hot packs applied to muscles, wearing heated garments etc generate heat in muscles and serve as an adequate warm up strategy in place of a dynamic/active warm up? To answer this, we can turn to new research by Chinese scientists, which has just been published in the ‘Journal of Sport and Health Science’(4).

In this study the researchers wanted to determine the effects of different warm-up types (active, exercise-based warm ups vs. passive warm ups) on muscle function and performance test criteria (maximum force generation and muscle contractile properties). When testing muscle function, the researchers looked at both voluntary contractions and evoked contractions. NB - voluntary muscle contractions are what we use in everyday movements (e.g lifting a weight or jumping), relying on the brain’s command to activate motor neurons in a natural, efficient order. Evoked contractions are induced by applying electrical pulses (via surface electrodes or nerve stimulation). They directly activate nerve axons, bypassing voluntary neural drive. This means they can test pure muscle response, and assess how much "extra" force could be elicited during a voluntary effort. The researchers also wanted to investigate the importance of warm-up task specificity - for example, if performing a warm up involving running is better at warming leg muscles than a cycling-based warm up). In addition, they looked at whether skin temperature measurement methods were adequate to estimate muscle temperatures, and how someone’s training status and sex might affect whether a particular warm up method is suitable.

What they did

This investigation took the form of a systematic search of all the previous research on this topic, using scientific databases such as PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane, Embase, and ProQuest. The search yielded 1272 articles, of which 33 met the inclusion criteria. The data from these studies was extracted and then combined and analyzed using powerful statistical methods (a so-called meta-analysis). Note that combining a lot of data from a large number of studies in a meta-analysis is a powerful way of producing robust conclusions. This analysis then looked at warm up type and activation method, various performance criterion, subject characteristics, and study design on temperature-related performance enhancement.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

· Increasing muscle temperature, through active or passive means, moderately improves dynamic, fast-velocity force production and rate of force development (contraction speed) but not maximal force capacity in both voluntary and electrically evoked contractions.

· Factors such as muscle temperature measurement method, the warm-up specificity, the athlete’s sex and training status do not seem to significantly impact the temperature increase-related performance enhancement.

· An active warm-up does not always lead to significantly greater performance increases than passive heating strategies, but the magnitude of enhancement may depend on the specifics of the active warm-up.

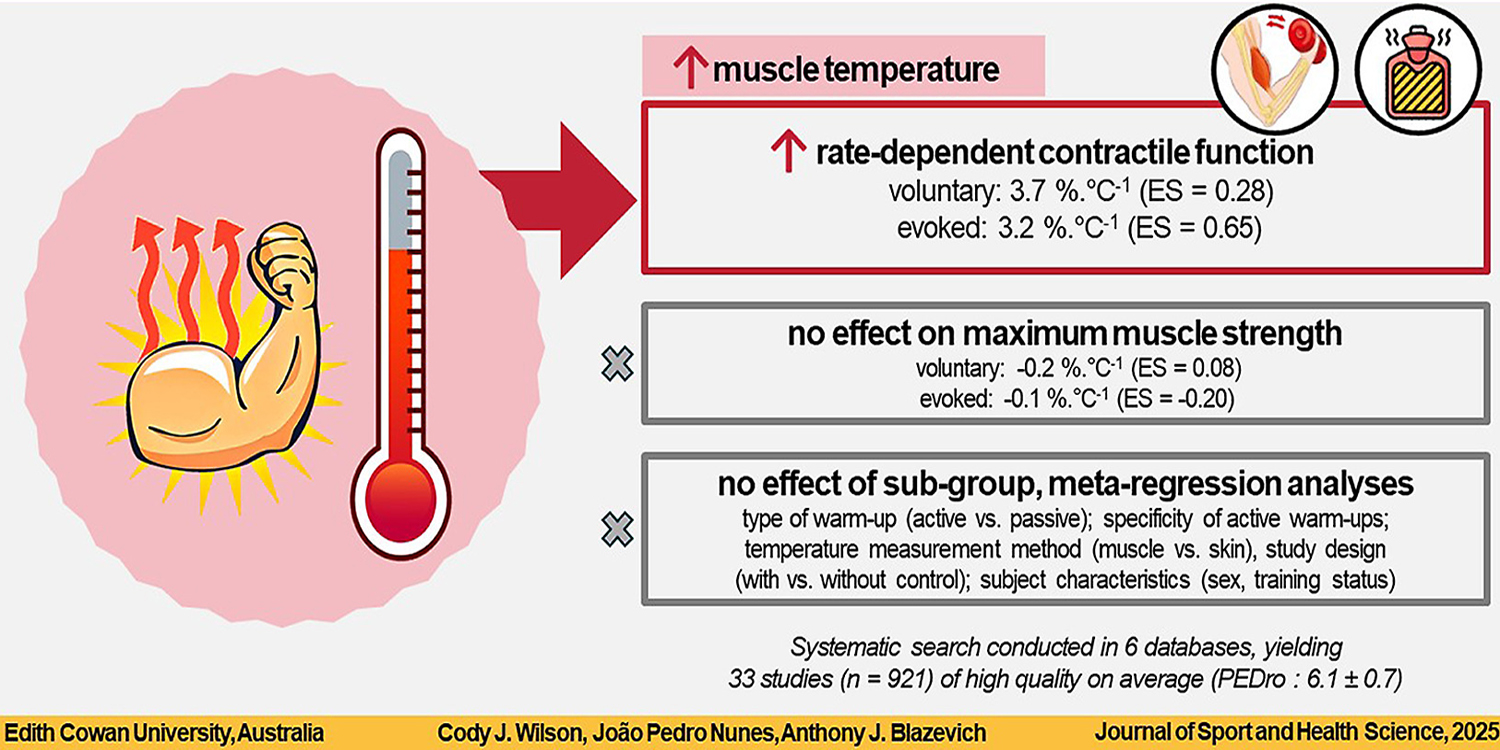

In their summing up (see figure 1), the researchers commented that increasing muscle temperature within the normal physiological ranges: 33.9°C to 39.7°C, irrespective of the warm-up type used – ie active/dynamic or stretching exercise-based or passively applied heat - had a significant positive effect on rate-dependent contractile function. For every 1oC of heat added to the muscle, there was a 3.5 % increase in function. However, adding heat made no difference to maximum muscle force production. Overall, their results demonstrated that (contrary to their expectations) increasing muscle temperature by any means improves the rate of force development, and therefore the speed and power produced during maximal effort contractions.

Figure 1: Summary of findings on active vs. passive (applied heat) warm ups

Practical implications for athletes

What this new research shows is that raising muscle temperature – however that is achieved – is what matters in a warm up. This appears to be particularly true for athletes whose sports require explosive power and sudden bursts of speed – eg soccer, basketball, tennis and rugby players, sprint athletes and swimmers etc. Both active warm ups (eg 10 to 15 minutes of dynamic drills or sport-specific exercises) and passive warms up (eg using heat wraps, hot water bottles heated garments etc) are equally effective in this regard, and this seems to held true regardless of your sport, whether you are male or female, novice, amateur or elite. The one caveat to this finding is that we don’t have enough data to be confident that this holds true for very sports-specific movements, which could be offer an additional benefit.

In practical terms, these findings expand the range of options for athletes. For example, if you can’t perform a sport-specific warm before an event, it seems that a non-specific warm up will do equally well, or you can simply apply heated wraps directly on the key muscle groups involved in your sport. In circumstances where you can perform a sports-specific normal warm up before an event but then have to wait several minutes on the start line, applying heat directly to your muscles will retain the benefits of that warm up. This research also suggests that including passive stretching in your warm up is perfectly feasible since you can prevent heat dissipation/loss by applying heat directly to the muscles during your stretching. Whichever type of warm up you perform, don’t forget that you need to raise your muscles’ temperature by around 2oC. You can easily check this temperature rise by using a infrared digital skin thermometer before and after your warm up. These thermometers are compact, cheap and readily available.

References

1. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018 Jun;50(6):1258-1266

2. Hum Mov Sci. 2017 Oct;55:189-195

3. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018 Jan-Feb;58(1-2):135-149

4. Journal of Sport and Health Science Volume 14, December 2025, 101024

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.