You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Energy deficiency: the bare bones of RED-S

SPB looks at new research investigating the impacts of relative energy deficiency (RED-S) on athlete health, explaining why and how and it should be avoided at all costs!

All athletes are (or should be aware) of the intimate connection between dietary habits and physical performance. But it’s not just about using nutrition to optimally fuel exercise and muscle growth/recovery. Dietary manipulation for weight management purposes can help athletes shed excess pounds, which almost invariably improves performance. This is especially true for sports where the force of gravity has to be overcome (for example in running and all running sports, cycling etc) and where a superior power-to-weight ratio is a key metric of performance.

The weight management danger

In their quest to improve performance, many athletes manipulate their diets with the goal of shedding excess weight. These weight management diets can help when used in a limited and controlled manner – for example, by eliminating empty/junk calories, or with mild calorie restriction for short periods of time. Some athletes approach weight management from the opposite direction – not by controlling calorie intake or quality, but simply by upping their training volume to shed some excess weight. Regardless of which weight management approach is used however, some athletes can over focus on weight and weight management, which in the longer term leads to unhealthy attitudes towards food/calories, health issues and poorer performance – ie eating disorders.

There’s no universally accepted definition of what constitutes ‘disordered eating’ in athletes, not least because there are several types of disordered eating behaviour, each with its own characteristics. What can be said however is that an eating disorder (ED) is characterised by an abnormal attitude towards food, which causes an athlete to change their eating habits and behaviour. In most cases, athletes with disordered eating tend to focus excessively on their weight and shape, leading them to make unhealthy choices about food, with damaging results to their long-term health and performance.

How common are eating disorders?

Despite the awareness among athletes and coaches about the issue of eating disorders, and the increased body of research into this topic, it remains an ongoing problem in both male but particularly female athletes, and across a wide range of participation levels. For example, a Norwegian study looked at over 1600 male and female elite athletes and compared the incidence of an ED with that in the general population(1). It found that many more athletes (13.5%) than controls (4.6%) had subclinical or clinical EDs. The prevalence of EDs among male athletes was four times higher in sports involving work against gravity (where low weight is an advantage) than in ball games (22% vs. 5%).

Meanwhile, the rate of ED among male endurance athletes was 9%. The prevalence of EDs among female athletes competing in aesthetic sports (high visibility sports such as swimming, gymnastics etc) was as much as 42% - higher than that observed in endurance sports (24%), technical sports (17%), and ball game sports (16%). The authors summed up their findings thus: “The prevalence of EDs is higher in athletes than in controls, higher in female athletes than in male athletes, and more common among those competing in leanness-dependent and weight-dependent sports than in other sports.”

Other studies into the problem of eating disorders have produced similar findings – ie that athletes participating in sports where ‘leaness’ is advantage or in aesthetic sports such as gymnastics are particularly at risk, especially female athletes. Moreover, this issue is one that is found across a wide range of sports and in many different nationalities and cultures; for example, studies report a high prevalence of eating disorders in French judo athletes(3)., Brazilian swimmers(4), US runners and high school athletes(5,6) – the list goes on.

Many of the earlier studies into eating disorders among athletes referred to the incidence of the ‘female triad’ in female athletes. The female athlete triad was defined as the interrelatedness of energy (calorie) availability, menstrual function, and bone mineral density (BMD)(7). BMD is a measure of the mineral content in bones, typically assessed to gauge bone strength and density; low levels increase fracture risk. Compared to the general female population, studies found a higher prevalence of abnormal menstrual function in the female athletic population(8-10), which is worrying because of its negative impact on bone mineral density(11). However, in 2014, the International Olympic Committee expanded this concept to RED-S (Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome), with the recognition that this condition can impact on both males and females(12). An updated 2023 IOC consensus further refined the definition, describing RED-S as ‘a syndrome causing impaired physiological functioning due to low energy availability, with consequences like compromised bone health, blood disorders, and elevated injury risk’(13).

RED-S and athletes

Just to clarify, RED-S refers to a condition in which (for whatever reason) athletes consume insufficient energy from food relative to the high demands of their training and competition, leading to disruptions in physiological functions. This imbalance can affect multiple body systems, including the musculoskeletal system, which encompasses bones and muscles. As we’ve mentioned above, athletes can unwittingly stumble into RED-S, either as a result of an over-enthusiastic approach to weight management, or as a result of a longer-term eating disorder. Regardless, these athletes (of both sexes) may experience declining sport performance as a result, often along with health complications like increased injury risk and even fractures.

Although a there’s been a lot of research into RED-S and the female triad, the underlying metabolic processes causing the condition are not well understood, particularly when it comes to bone metabolism. Bone metabolism involves the balance between bone formation (building new bone by cells called osteoblasts) and bone resorption (breaking down of old bone by cells called osteoclasts). Some research has indicated that athletes with RED-S suffer from suppressed bone metabolism(14); however, few studies have investigated the direct link between these changes directly to BMD within the same group of individuals. Also, much of the research to date has focused solely on female athletes (female triad studies), thereby overlooking male athletes who make up around one fifth of the total number of RED-S diagnoses(13).

New RED-S research

To try and understand more about exactly how RED-S affects bone health in elite athletes, a team of German scientists have carried out a study to clarify how RED-S leads to bone deterioration in athletes, and the implications for early detection to prevent injuries, and sustain athletic careers(15). Published in the Journal of Cachexia Sarcopenia and Muscle, this study drew parallels between RED-S and a condition known as ‘cachexia’, which is a wasting syndrome characterized by severe loss of muscle and fat tissue often seen in chronic illnesses like cancer. While elite athletes typically build strength through rigorous exercise, those with RED-S often struggle to do this and instead often experience tissue breakdown similar to that seen in cachexia. This results in poor bone quality, higher injury rates, and reduced performance.

To carry out the study, the researchers analyzed patient records from 82 elite athletes (25 women and 57 men, average age 23.4 years) who were treated at the Department of Osteology and Biomechanics, University of Hamburg-Eppendorf Medical Centre, Germany, between June 2013 and November 2023. The athletes’ elite status was defined as performing at least 21 hours of weekly training or competition at national/international levels. In addition (to add further rigor to the study), athletes were also classified using the McKay system,- a scientifically validated method, which tiers sports by performance level, with all participants being classified at Tier 3 or higher (51% at Tier 4 or 5).

What they did

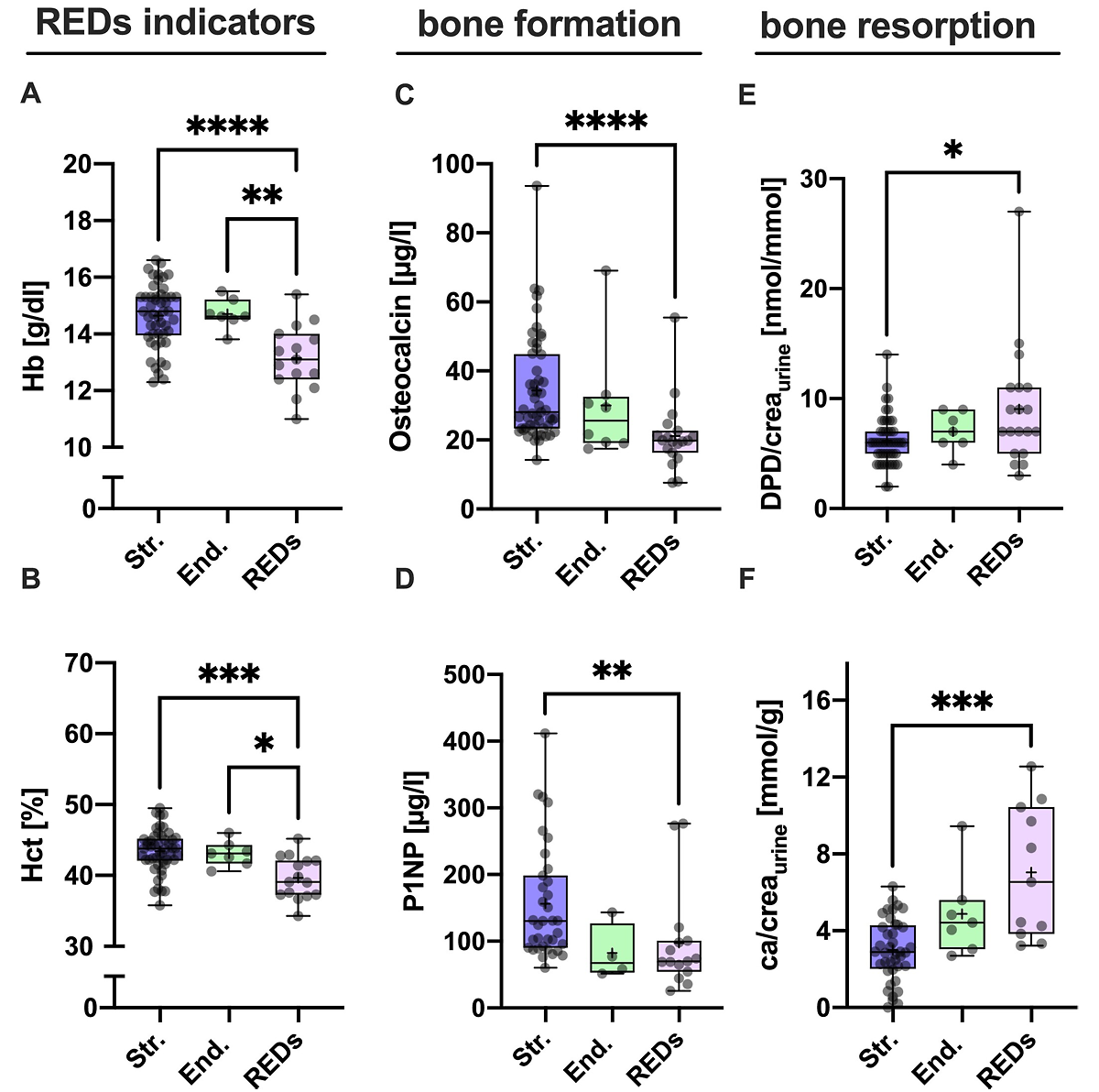

The first step was to determine how many of the athletes treated over that period had been suffering from RED-S at the time. To diagnose RED-S from this historical data, the researchers looked back at notes made during consultations, the athletes’ documented training history, any recorded performance dips, the athletes’ history of fractures (verified by X-rays or scans), plus the results of routine blood and urine tests. This data was then assessed using a tool called the REDs Clinical Assessment Tool Version 2 (CAT2), which is derived from the 2023 IOC guidelines(13). This scores risk based on a number of factors, including energy intake, menstrual cycles (in women), bone density, and injuries—categorized as low-risk (green), mild (yellow), moderate-to-high (orange), or very high-to-extreme (red). When this scoring was complete, it turned out that about 24% of the athletes (mostly endurance athletes) had been suffering from RED-S at the time of their injury diagnosis and treatment. Of particular interest for bone metabolism were the blood and urine tests. These included:

· Tests for bone turnover markers. These gauge how bones build up (formation) and break down (resorption). Formation markers like osteocalcin and P1NP (proteins from bone-building cells called osteoblasts) indicate new bone creation. Resorption markers like deoxypyridinoline (DPD) and calcium in urine indicate bone breakdown by osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells).

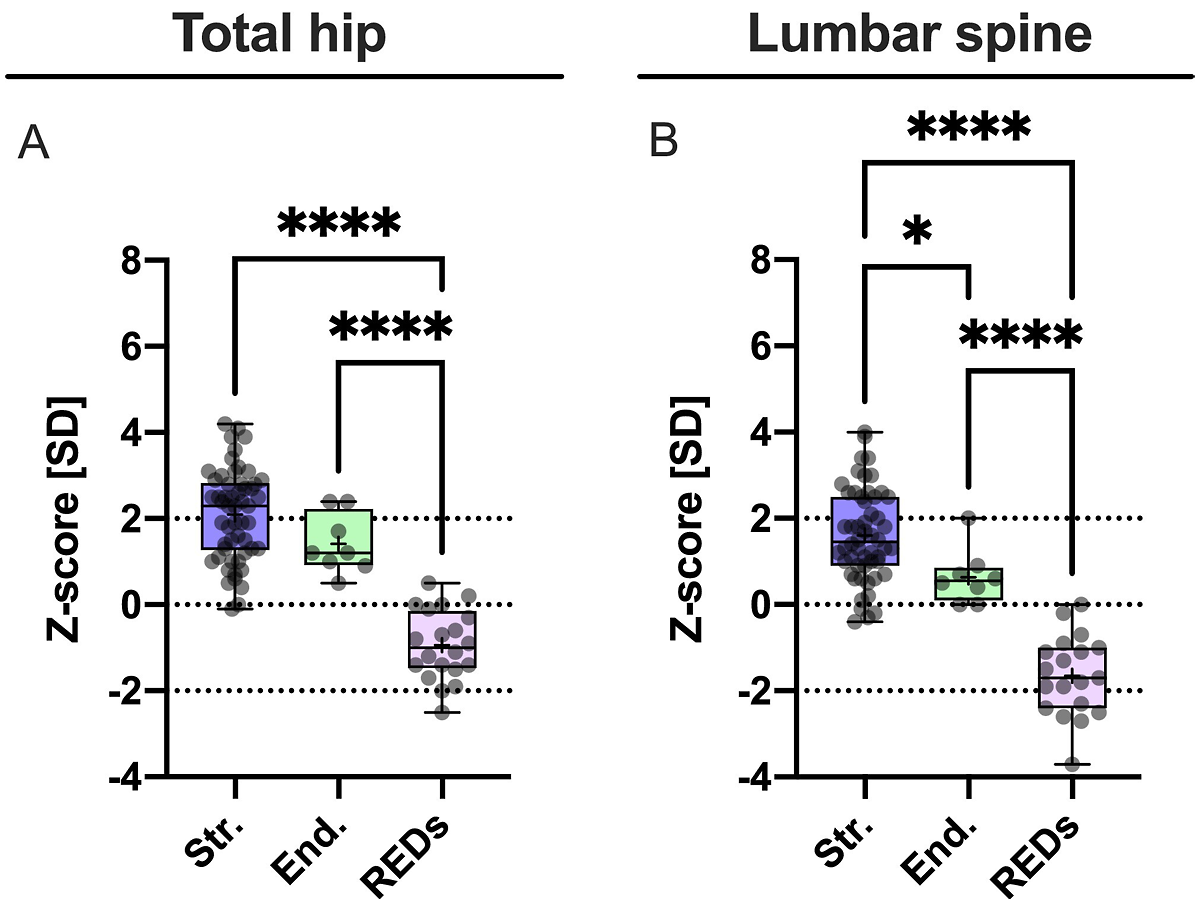

· Bone density scans at the spine and hips using a very accurate technique known as Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA). DXA can measure ‘area bone mineral density’ (aBMD), which is the bone mineral content per unit area of bone. This yields ‘Z-scores’, which compare results to age- and sex-matched norms. A score below -2.0 signals low density.

· Advanced microstructure imaging of the wrist (radius) and ankle (tibia), using high-resolution computed tomography (CT). This yields a detailed scan assessing 3-dimensional bone mineral density per volume (vBMD), and shows the bone micro-architecture, including tiny structures like trabeculae (spongy bone struts) and cortical bone (dense outer shell).

Once all the data was gathered, the stats were crunched to provide a robust comparison between athletes who were suffering from RED-S vs. those who were not. In addition, the researchers looked to see how sport type impacted the findings.

What they found

There were a number of key findings, many of which have profound implications for athletes at risk of RED-S (see figures 1 and 2):

· Firstly, RED-S was far more prevalent in endurance athletes; 69% of athletes in endurance sports were diagnosed with it compared with just 3.6% of strength athletes.

· Stress fractures (not full breaks but bone cracks from overuse) were far more common in the athletes diagnosed with RED-S cases compared with non-RED-S athletes (80% vs. 34% respectively). This finding highlights the increased risk of fracture vulnerability in RED-S.

· RED-S diagnosed athletes were found to have lower levels of hemoglobin (Hb - oxygen-carrying component in red blood cells) and hematocrit (a measure of red blood cell volume), which together results in poorer oxygen delivery to tissues, and thus poorer performance.

· Bone formation in the RED-S athletes was suppressed compared to the non-RED-S athletes. Markers of bone formation (eg osteocalcin) were 38% lower while markers of breakdown (eg DPD) were 46% higher, with urinary calcium excretion being tripled. Overall, this combination creates a net bone calcium loss – rather like continually withdrawing funds from a bank account faster than deposits are made. The researchers found that this imbalance mimicked the metabolic chaos of cachexia but stemmed from dietary shortfalls in calories and nutrients rather - not disease.

· DXA scans showed that the RED-S athletes had alarmingly low Z-scores: -1.65 at the spine and -0.94 at the hip. This was in stark contrast to the positive Z-scores of the strength athletes). So low were these scores in the RED-S athletes that 32% of them would have been classified as having osteoporosis-like low density at the spine!

· Last but not least, the high-res CT scans showed a grim picture of bone quality micro-architecture in the RED-S athletes; bone volume density was reduced by 10-18% at both the radius of the wrist and tibia (shin bone). There were fewer, thinner trabeculae and slimmer cortical shells meaning more fragile bone architecture, prone to cracks under stress.

Figure 1: Indicators of RED-S, and markers of bone formation/loss

Figure 2: Hip and lumbar Z-scores from DXA scans

Implications for athletes

The main take-home lesson from this new study is that RED-S in athletes acts rather like a ‘silent thief’ of bone mineral content and structure. Despite there being no obvious bone symptoms, RED-S promotes bone loss and impairs bone repair regardless of the athlete’s training (something that normally BOOSTS bone health), especially where training involves strength work. The low energy availability in RED-S almost certainly drives these changes via hormonal disruptions such as reduced estrogen/testosterone, which impairs bone formation, while the elevated levels of cortisol promote bone loss. This metabolic imbalance hinders the process of ‘mechanotransduction’ - the process by which mechanical stress from exercise stimulates bone remodelling. This in turn leads to inadequate bone adaptations under training loads, causing vulnerability to stress fracture at weight-bearing sites like the tibia.

In the RED-S athletes who were subsequently treated at the University Medical Centre, most were prescribed vitamin D (80%) and calcium (60%) supplements. That’s because higher calcium intakes combined with vitamin D are known to help improve bone density in otherwise healthy adults(16). RED-S athletes who suffered the lowest levels of BMD were also prescribed bone-building medications such as teriparatide (20% - helps promote bone formation) or bisphosphonates (13% - helps reduce bone breakdown). When these treated athletes were checked over a year later, two thirds of them showed BMD improvements; unfortunately however, this also means that a third of the athletes showed no improvement.

It should be abundantly clear from the above that RED-S is a real threat to athlete health and performance, and should therefore be avoided at all costs. Some athletes stumble into RED-S by simply underestimating their daily energy needs or by over enthusiastic weight management strategies. With other athletes, longer-term eating habits – possibly dysfunctional – may come into play. Regardless, the key to prevention is to be on the lookout, recognize if you may be at risk and then take steps to improve your energy availability. This article by Alicia Filley provides a great starting point to help you understand the potential pitfalls of RED-S, how it arises, and (importantly) how to navigate out of it.

Another recommendation for athletes who may be at risk is to undertake some regular strength training (1-2 times per week). Not only can strength training help reduce the likelihood of bone density loss/degradation, its addition will almost certainly help improve performance! A further way to help maintain bone health is to ensure a plentiful intake of dietary calcium and vitamin D. Here are some tips to help:

· Emphasize the importance of both calcium-rich and vitamin D-rich foods in the diet. For vitamin D: oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, herring, sardines, pilchards etc are excellent sources; for calcium: milk, yoghurt, cheeses, nuts and seeds should all be consumed regularly.

· Bear in mind seasonal fluctuations in vitamin D status; athletes living and training at northerly latitudes will probably benefit from routine supplementation from October to March (blood tests are readily available that can identify a sub-optimal vitamin D status – ie below 75ng/L).

· Encourage some regular sun exposure to boost vitamin D levels; 15-20 minutes per day in strong sunshine without sun cream is ideal (cover up after that though).

References

1. Clin J Sport Med. 2004 Jan;14(1):25-32

2. American Psychiatric Association: “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM-IV-TR), 4th Edition, June 2000

3. Int J Sports Med. 2007 Apr;28(4):340-5

4. Nutrition 2009 Jun;25(6):634-9

5. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 May;35(5):711-9

6. Phys Ther Sport. 2011 Aug;12(3):108-16

7. Med Sci Sports Exerc; 2007;39(10):1867-1882

8. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12(3):281-293

9. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19(5):421-428

I0. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(1):65-72

11. Bone. 2007;41(3):371-377

12. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014. 48: 491–497

13. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023. 57 1073–1098

14. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2022. 37: 1915–1925 Journal of Physiology 2019. 597: 4779–4796

15. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2025 Oct;16(5):e70082

16. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015 Oct;25(5):510-24

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.