You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Good sleep: train early or burn the midnight oil?

SPB explores the relationship between training times and sleep quality, and highlights new research for athletes who train hard but need the best night’s sleep possible!

In recent years, scientists have established that sleep and sport/exercise performance have a strong relationship, each mutually influencing the other, both positively or negatively. Get your sleep health right and performance is likely to be enhanced. However broken or insufficient sleep is not good for performance. In terms of physiological recovery, sleep is vital – not least because a number of hormonal responses take place in the lead up to and during sleep.

One important hormone relating to athletic recovery is growth hormone. Growth hormone is necessary for body restoration, and plays an important role in muscle growth and repair(1,2). Muscle growth, repair, and bone building are vital for athletic recovery following strenuous training and competition; it has been reported that 95% of the daily production of growth hormone is released from the pituitary gland in the endocrine system during non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM - ie deep sleep). Therefore NREM sleep is considered the time in which the body actively repairs and restores itself(3,4).

Sleep quality matters

Given the physiological and biochemical impacts that sleep helps facilitate in the human body, it follows that anything that impairs the length or quality of sleep in an athlete can also be detrimental to maximizing the speed of recovery, and therefore subsequent performance – and research has established that this is indeed the case(5,6). In particular, sleep deprivation is associated with higher rating of perceived effort (RPE) values, potentially leading to reduced performance, particularly in endurance events. In short, when you’re sleep deprived, you will feel like you’re working harder to sustain a given workload compared to when sleep amounts have been adequate.

Training timing and sleep quality

Since optimum recovery from training requires adequate sleep quality and quantity, and that sleep quality (and to a lesser extent quantity) can be in turn affected by training timing, the question arises of how best to time training sessions to maximize sleep quality, and therefore ensure more rapid recovery. This is a topic that a number of studies have tried to answer.

One US study examined the relationship between sleep quality and time/intensity of exercise undertaken that day(7). To do this, researchers looked at the sleeping and exercise habits of 1000 adults aged 23-60 years from a wide variety of US geographical regions. In particular, the researchers asked the subjects to report their sleep quality, total sleep time, sleep latency (how long it took them to fall asleep) and how often they woke without feeling refreshed in the morning. The timing of that day’s exercise was also recorded and split into one of three categories:

· More than 8 hours before bedtime

· Between 4-8 hours before bedtime

· Less than 4 hour before bedtime

The results showed that training late in the evening had no detrimental effect on sleep quality; compared to those who exercised more than four hours before bedtime, those who exercised nearer to bedtime reported no difference in their sleep quality, total sleeping time, sleep latency or how often they woke without feeling refreshed in the morning. This was the case regardless of whether the ‘late trainers’ had exercised at moderate intensity or vigorously prior to bedtime. Having said that, the highest scores for sleep quality were for those who had exercised vigorously in the morning – these subjects had the lowest likelihood of waking up in the night and not feeling refreshed in the morning.

These findings tie in somewhat with research carried out the previous year by Chinese researchers who examined the effect of evening exercise in 5086 students(8). This study found that moderate-intensity exercise such as steady-state jogging and cycling performed late in the evening had no negative impact on the students’ sleep quality. However, unlike the US study above, very intense exercise performed later in the evening DID seem to harm sleep quality.

Training timing and sleep quality in highly-trained endurance athletes

Although both of the above studies investigated sleep timings in healthy, recreationally active adults, the findings come with a caveat: while the subjects were exercising regularly, they were not classed as athletes. This is important because for any given workload, the body of a highly trained athlete will be under much less relative physiological stress than would be experienced by a relatively untrained person. Also, lower volumes of low-moderate intensity exercise do not produce the same kind of hormonal impacts that higher exercise volumes and intensities (more typically used by athletes in training) do.

In 2019, a study by Spanish scientists addressed this concern by investigating ultra-endurance runners, whose training volumes and intensities are probably much more representative of most endurance athletes who train seriously(9). In this study, the scientists analysed the effect of the intensity and the hour of the training session on sleep quality and ‘cardiac autonomic activity’ (cardiac autonomic activity refers to the subconscious nervous control of the cardiovascular system, and includes heart rate variability, which is often measured as a determinant of physiological recovery after exercise).

All the runners underwent four trials (separated by 72 hours) after which sleep quality and cardiac activity were monitored over the course of the following night. These trials were as follows:

· Morning training at moderate intensity

· Morning training at vigorous intensity

· Evening training at moderate intensity

· Evening training at vigorous intensity

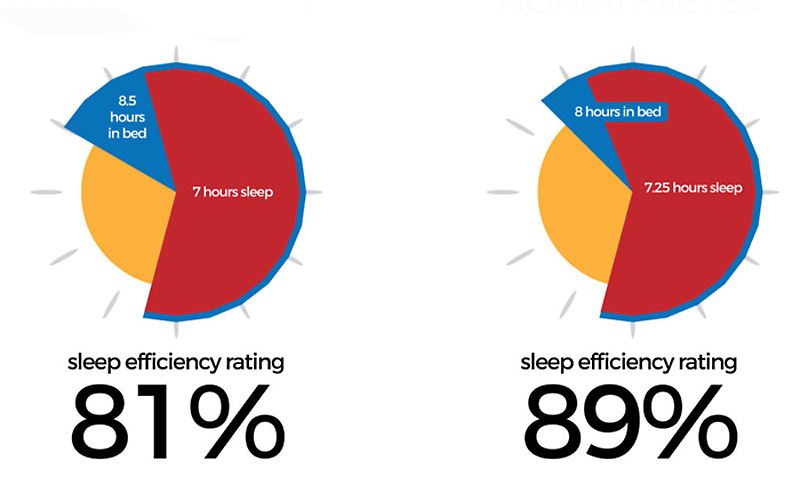

As well as subjective sleep quality and nocturnal cardiac autonomic activity, the researchers also recorded the runners’ sleep efficiency using sleep actigraphs. Sleep efficiency (see figure 2) is a measure of how rapid sleep onset is, and whether sleep is interrupted by waking periods. A high sleep efficiency means that someone falls asleep very quickly after retiring and experiences minimal periods of wakefulness during the sleep period.

Figure 2: Sleep efficiency

What they found was that both training intensity and the timing of that training impacted sleep quality. With intensity for example, when morning training was conducted, moderate intensity sessions led to significantly calmer sleep (ie with less movement) than when high-intensity sessions were conducted. Also, a vigorous morning training session produced poorer subjective sleep that a moderate evening training session. However, training timing also seemed to matter. Higher sleep efficiency was observed when the training was performed in the morning compared to the evening sessions at both moderate and high intensities. There were also significantly lower numbers of awakenings during the night were observed when the training had been performed in the morning compared to the evening

Most recent research

The studies mentioned above produced mixed findings; some found very little impact on pre-sleep exercise timing and intensity, while the study on ultra-endurance athletes found that training near to bedtime, especially training vigorously, led to poorer sleep quality. To try and clarify the data, a recent literature review conducted 18 months ago analyzed results from almost 30 previous studies in order to compare the effects of different intensities of acute evening exercise on sleep in healthy adults(10). It found that overall, acute evening exercise completed before bedtime did not disrupt subsequent sleep regardless of intensity.

However, there’s still much confusion about this topic because most of the studies reviewed above looked at ‘healthy adults’ rather than people performing regular training. When it comes to the latter, a study conducted nine months ago by a team of French and Canadian scientists found contradictory results(11). This study investigated the effects of afternoon compared to evening exercise in 42 young adolescent athletes and found that that evening training led to lower sleep efficiency and longer sleep onset latency compared to afternoon training.

Interestingly, this effect seemed to be related to whether athletes were ‘owls’ or ‘larks’. Owl/lark tendency is a function of underlying daily biorhythms; larks are individuals who are naturally ‘morning’ people. Larks find it easy to get up early and perform well early in the morning but struggle to stay awake late at night. Owls have a much later body clock. They struggle to get up and function in the morning but perform well in the evening and find staying up late easy. In the study on young athletes, those who were owls tolerated late training very well. However, the athletes with lark tendencies really struggled with late training.

Sleep, cortisol and exercise type

One theory for the variable findings on training timing and sleep quality involves the amount of physiological arousal in the brain produced by exercise. In particular, acute exercise activates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity in the brain, which in turns leads to the release of the hormone cortisol(12,13). This effect is known to be more pronounced when endurance exercise is performed compared to resistance exercise(14).

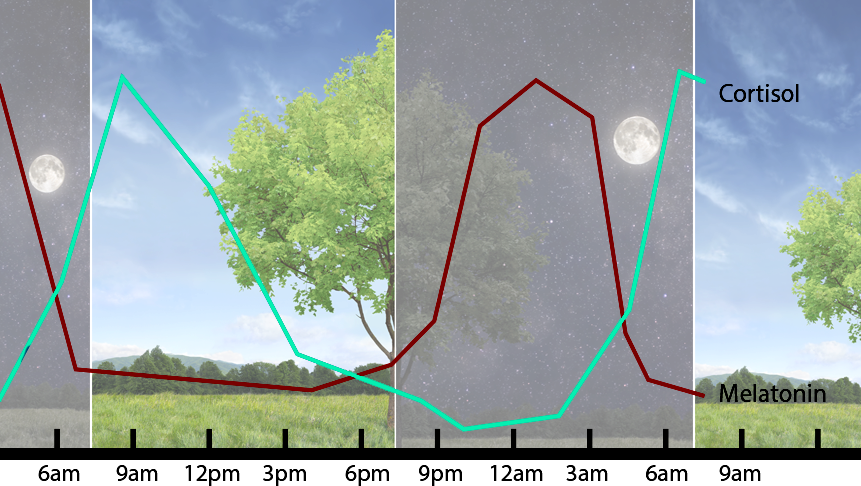

Cortisol release follows a diurnal pattern in which levels decrease throughout the day, reach their lowest levels overnight, and then increase rapidly just before and during awakening(see figure 2)(15). The increase during morning awakening is called the cortisol awakening response (CAR)(16). Since cortisol levels should reach their minimum values during the evening and early part of the night, it is easy to understand how performing exercise in the evening (especially vigorous endurance exercise) could disrupt this natural rhythm, leading to altered brain activity during sleep, resulting in poorer sleep quality.

Figure 2: Natural rhythm of cortisol (and melatonin) secretion*

Related Files

Cortisol levels rise steeply in the morning as part of waking process. They then decline through the day, reaching a minimum during early and late evening. Note that the pattern of melatonin (the ‘sleep hormone’) secretion is almost the inverse of cortisol secretion. *NB – image courtesy of Dr Jockers (www.drjockers.com).

New research

To try and find some definitive answers, a team of French researchers have carried out a brand new study investigating the effects of two types of evening exercise – endurance and resistance – on sleep quantity and quality(17). Published in the journal ‘Frontiers in Physiology’, this study was a finely-tuned investigation of sleep using a technique (known as sleep spectral analysis) and measurements of cortisol levels. The researchers hypothesized that evening exercise (especially endurance exercise) may lead to increased physiological and cortical arousal compare to no evening exercise, and that this increased arousal would be accompanied with lower sleep quantity and/or quality.

What they did

Sixteen participants were recruited (12 males and 4 females) for this study. All the participants had to meet strict criteria, including minimal intakes of caffeine and alcohol, and non-users of medications known to interfere with or influence sleep patterns. In particular, all had to have a regular bedtime between 09:30pm and 12:30am. In a randomized order the participants performed three separate trials on three separate occasions, each separated by a week. These were as follows:

· Evening endurance – thirty minutes of light exercise at 10pm consisting of 30 minutes of steady-state pedaling on a stationary bike at 60rpm with a modest workload set at 1.18 × body weight (kg) + 5.51 Watts.

· Evening resistance – thirty minutes of resistance exercise at 10pm consisting of 72 bouts of 5 seconds of pedaling, each followed by 20 seconds of rest on a stationary bike at a workload of 5.89 × body weight (kg) + 27.54 Watts.

· Control condition – 30 minutes of sitting passively on a chair at 10pm.

Importantly, the workloads were set so that the endurance and the resistance sessions involved exactly the same amount of energy expenditure over the same time period.

Following each trial, the participants went to bed at 11.00pm and were awakened at 7.00am. They were also instructed to not perform exercise of any intensity the day of each session. Measures of salivary cortisol were taken immediate after the 30-minute period of exercise (or rest). Sleep quality and quantity was recorded in the laboratory using a technique known as ‘ambulatory polysomnography’. This a procedure that utilizes brainwave data, eye-movement monitoring, skeletal muscle electrical activity data, electrical activity of the heart, blood oxygenation well as airflow and respiratory effort during breathing to finely analyze sleep quality.

What they found

The results showed that that light-moderate intensity exercise (both endurance and resistance) completed 30 minutes before bedtime resulted in lower sleep quality and quantity than the control condition with no exercise. The full results can be seen in this table, but some of the key finding on sleep onset and duration are shown in table 1 below.

Table 1: Sleep onset and durations in each condition

|

Control |

Endurance exercise |

Resistance exercise |

|

|

Sleep onset latency (minutes) |

14.43 |

21.46 |

21.53 |

|

Sleep efficiency (%) |

93.34 |

90.49 |

91.05 |

|

Total sleep time (minutes) |

412 |

394 |

406 |

|

Total wake duration after sleep onset (minutes) |

26.54 |

39.25 |

37.29 |

Compared to the control condition, the changes in sleep quality and quantity were only small (especially for the resistance session) and would likely not adversely impact performance the next day. However, when it came to the data on brainwave activity, the results showed that in contrast to the resistance exercise, performing endurance exercise led to an increase in EEG activity associated with hyperarousal during sleep and higher cortisol levels – thus indicating a real hyperarousal effect of endurance exercise performed in the evening.

Implications for athletes

When it comes to exercise timing and sleep quality, there are quite a lot of conflicting findings, so what ‘best-evidence’ take home messages are there for athletes? In the study above, the results suggest that performing exercise late in the evening does have a slight impact, but one that is quite small, especially if the exercise is resistance-training based. However, there’s no denying that there was increased arousal, which did affect sleep quality, especially when endurance exercise was performed. Bear in mind too that this endurance exercise was actually quite light in nature (around 120 watts for an 80kg adult); at more normal (ie higher) endurance training intensities, it’s probable that the negative effects would have been amplified.

It’s also likely that your tolerance of evening exercise is not just a function of exercise type (ie whether endurance or resistance) and intensity, but also how close to bedtime that training is performed and your own degree of lark/owl characteristics. Larks tend to retire earlier and have cortisol levels that are lower in the evening compared to owls. So for them, performing exercise that causes a significant rise in cortisol levels (ie moderate-to-hard endurance sessions) is far more disruptive than in owls, whose body clocks run later and whose cortisol levels decline later in the evening.

Putting all the data together, the best-evidence advice for athletes at this current moment is as follows:

· When sleep quality really matters (for example if you are trying to catch up on missed sleep), training in the morning or afternoon is preferable to training in the evening.

· The above recommendation is especially true for larks but may be less relevant for owls.

· When performing both endurance and strength sessions in a single day, sleep quality will likely be enhanced if endurance training is performed in the morning and strength in the afternoon or early evening rather than vice-versa.

· If you need to perform intense training sessions, try to get these done by late afternoon (especially if you are a lark).

· Regardless of timing, intense training sessions are more likely to negatively impact your sleep that night. So if you really need a good night’s sleep for the next day (eg before an important presentation, exam etc), a low-moderate intensity session that day is better than an intense one.

· As a rule of thumb, the nearer to bedtime you train and the more intense that training is, the more chance you will suffer poorer sleep quality, especially when performing endurance training.

· Remember that everyone is unique; if you experiment with training timings and find what works for you in terms of getting restful sleep, it doesn’t matter if it goes against the grain of these general recommendations!

References

1. Biol Rhythm Res. 2009;40(1):45–52

2. Eur J Sport Sci. 2008;8(2):119–126.29–31

3. Annu Rev Med. 1976;27:225–243

4. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(1):S75–S84

5. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45: 2243–2253

6. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;107: 155–161

7. Sleep Medicine 2014. 15(7), 755-761

8. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013 Jun;47(6):542-6

9. Physiol Behav. 2019 Jan 1;198:134-139

10. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2022; 14, 2157–2177

11. Sleep 2023. 11 juill 46 (7), zsad099. 10.1093/sleep/zsad099

12. Neuroimmunomodulation 2009; 16 (5), 284–289

13. Front. Neuroendocrinol 2017. janv 44, 83–102

14. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol 2016. août 116 (8), 1503–1509

15. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2009;72:67–73

16. Psychosom. Med. 2004;66:207–214

17. Front Physiol. 2024; 15: 1313545. Published online 2024 Jan 23. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2024.1313545

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.