You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Injury prevention: the Ys and wherefores of balance testing

SPB looks at new research on injury-risk screening and how runners can use these findings to reduce their risk of sustaining a future injury

As regular SPB readers will know, getting the best out of your training to produce maximum fitness and performance gains is not a straightforward process. Not only are there are endless permutations of training approaches that can be utilized, but you also have to know how to blend them together in a carefully designed program for success. However, no matter how knowledgeable you are and how meticulously planned your training program is, it can very quickly go to pot if an injury strikes. Quite apart from the fitness losses that occur as a result of detraining, being sidelined with an injury can also be very frustrating and stressful! As the old saying goes: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”, so preventing injuries from occurring in the first place should be an important consideration in any training program.

Running and injury prevention

The prevention of injury is particularly relevant to runners, where the risk of lower-limb injury is comparatively high(1). For example, in a 6-month study of 87 recreational runners, at least one lower limb injury was suffered by 79% of the runners during the observation period(2). In another study of 583 habitual recreational runners, researchers found that over the 12-month observation period, 252 men (52%) and 48 women (49%) reported at least one lower-limb injury that was severe enough to affect running habits, resulting in a visit to a health professional, or requiring the use of medication(3). Among the wider running population as a whole, research suggests that the risk of sustaining a lower-limb injury can be anything from one injury per 147 hours of training to as high as one injury per 17 hours of training(1).

The question of course is how to reduce the risk of injury. At the heart of any injury-prevention strategy should of course be a properly designed program, which allows runners to adequately recover in between training sessions, and one that doesn’t increase either volume or intensity too rapidly, or suddenly introduce new challenges like large amounts of hill or off-road running. In addition, correct footwear is vital along with appropriate ancillary training such as stretching and strengthening to build as much ‘resilience’ as possible. But even when runners do all of the above, injury can strike – often completely out of the blue. The question then is whether there’s any way of predicting when an injury might strike – for example some kind of screening or testing procedure that runners can carry out for themselves?

The Y-Balance Lower Quarter (YBT-LQ) test

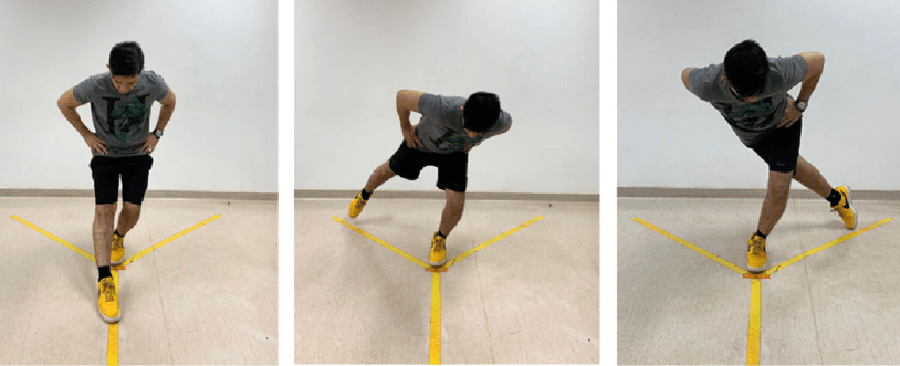

One screening test that has been the subject of extensive research in the context of injury prediction is the ‘Y-Balance Lower Quarter (YBT-LQ) test’. In this very simple test (see the excellent video below to understand how it is performed), the athlete being tested stands on one leg at the apex of the letter ‘Y’, which is marked on the floor with chalk or tape.

He/she reaches as far as possible with the other leg, lightly touching in each of the three directions of the Y shape along the lines that form the Y mark. These directions are (see figure 1):

· Anterior (forward)

· Posterolateral (backward and outward)

· Posteromedial (backward and inward)

Figure 1: The three directions of the Y-Balance Lower Quarter (YBT-LQ) test

During the test, it is the strength, balance and coordination of the stance leg that is being evaluated. The legs are then swapped over (ie stance leg becomes the reaching leg and vice-versa) and the test is repeated. The distances reached on each leg are measured, and used to calculate asymmetries between the left and right legs. The idea is to evaluate balance, strength, and mobility and potentially flag injury risk if there are significant asymmetries between the scores for the right leg and those for the left leg.

Is the Y-Balance test valid?

Although popular as a screening tool to predict injury risk in athlete, there’s much debate about how reliable and relevant the Y-balance test is. Some studies have suggested it has value, particularly in specific populations, whereas critics have argued that there are simply too many other factors that can impact injury risk (eg sport type, sex, training load, fatigue, previous injuries etc) to pin down a universal threshold for future injury risk.

A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis study (a study that pools all the data from previous studies on a topic to come up with more robust conclusions) investigated the reliability of the YBT-LQ test to determine if and how performance scores on the test varies among different populations (ie sex, sport/activity, and competition level), and to determine whether asymmetry, individual reach direction performance, or composite scores were able to predict injury risk(4).

Fifty-seven studies were included, with nine studies assessing test-to-test reliability, 36 assessing population differences, and 16 assessing injury prediction. The results showed that both the biological sex of the athlete and their sport affected the numerical scores achieved in the posterolateral (backward and outward) and posteromedial (backward and inward) parts of the test but not in the anterior (forward) part. Overall, these differences meant that it’s not reliable to calculate a threshold score for future injury risk unless there is gross asymmetry or that score has been developed for a specific group of athletes (eg female distance runners, male soccer players etc).

Male runners and the Y-balance test

With the above in mind, brand new research published earlier this month makes for very interesting reading if you are a male recreational runner(5). In this study, researchers looked at the power of the Y-balance test for predicting a future plantar fasciitis injury in male recreational runners who were undergoing training in preparation for a marathon. Plantar fasciitis is a debilitating condition that causes pain and inflammation in the connective (fascial) tissues of the base of the feet, and is the third most common type of running-related overuse injury(6).

To do this, 172 male recreational marathon runners underwent the Y-balance test and were then tracked and monitored for plantar fasciitis development during a 3-month follow-up period. Of the 172 participants, 12 (7% of the marathon runners) went on to develop the condition during the three months. Their baseline data from the Y-balance test were then compared to those of runners who remained uninjured. The key finding was that the asymmetry in the posterolateral reach (middle picture in figure 1) was very significantly greater in the injured runners than in uninjured runners. In fact, for every 1cm increase in the asymmetry between right and left legs in the posterolateral reach, the risk of developing plantar fasciitis was increased by 18.3%. Further analysis showed that more generally, across this cohort (male recreational runners), a posterolateral reach asymmetry greater than 4.5cm was a strong risk factor for the development of plantar fasciitis.

Implications for runners

In their conclusions, the authors recommended that male recreational runners (and those who coach them) should aim to try and reduce inter-limb asymmetry as part of an injury prevention and treatment strategy. And given the Y-balance test is a simple and repeatable way of measuring asymmetry, using it on a regular basis could be worthwhile, especially in sports such as distance running where repetitive movements performed with small imbalances in flexibility, range of movement or strength can lead to cumulative stress and injury over time. In the case of male distance runners, an inter-limb asymmetry of more than 4.5cm in posterolateral reach is definitely worth addressing as it appears to significantly increase the risk of plantar fasciitis. More generally, the Y-balance test is a useful identifier of asymmetry, which is particularly relevant in strength asymmetries, because it is known that when asymmetry become large (over 10-15%) there is likely to be a detriment to performance and an increased injury risk(7).

When trying to reduce inter-limb asymmetry, the key is to undertake unilateral leg strength or flexibility training, where the left and right legs are trained separately. For strength, good examples of these include reverse dumbbell or barbell lunges, single leg presses, Bulgarian split squats. You can see these being performed in the three video clips below:

For some additional examples of good single leg exercises, watch this video clip:

In all cases, it is important to ensure that the range of movement you work through and the speed of movement are identical for both legs. You should also work your less dominant leg first, making a mental note of how many reps were achieved and then follow up with the dominant leg, but ensuring you perform only the same number of reps (not more). Over time, your leg strength will even out, which will hopefully reduce your asymmetry (and your injury risk). Which you can verify by repeating the Y-balance test at regular intervals!

References

1. J Physiotherapy 2013; 59(4) 263-269

2. Br J Sports Med . 2004 Oct;38(5):576-80

3. Arch Intern Med. 1989 149(11):2565-8

4. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2021 Oct 1;16(5):1190–1209

5. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2025 Mar 13. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.25.16562-6. Online ahead of print.

6. Sports Med. 2012 Oct 1;42(10):891-905

7. J Sports Sci Med. 2021 Oct 1;20(4):594-617

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.