You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Injury prevention: time to self assess?

What is the risk of injury in runners undergoing marathon training, who is at particular risk, and what conditioning exercises might help reduce that risk? SPB looks at new research

There are good reasons why running is such a popular sport; it produces high levels of aerobic fitness in a time-efficient manner, it can be done anytime, anywhere, and it only requires a minimal outlay for equipment (just decent shoes needed). However, there is a downside for runners, especially who train and compete recreationally or at the amateur level, and that is the risk of picking up a running-related injury (RRI).

Data accumulated over a 15-year period shows that in any 12-month period, lower extremity RRIs occur in an estimated 50% or so of recreational runners, with some studies suggesting this to be even higher(1-3). When injury strikes, even the best training plan and personal goals can go out of the window, which means that understanding the risk factor for RRIs and trying to reduce the likelihood of injury is very important, especially when training for a demanding event such as a marathon.

Risk factors for RRIs

Since RRIs are so prevalent in runners, it is important to be aware which factors may influence risk. There are a number of proposed causal factor for RRIs in runners, including a sudden increase in training volume or intensity, a change of running surface, incorrect shoe selection and biomechanical imbalances in runners themselves. Common to many of these factors is an increase in high-impact loading, and research suggests that high-impact loading is indeed a key factor in RRI risk(4,5). Being a novice runner with less than a year’s experience, being a much older runner and not following a structured program also increase injury risk(6). Also, as discussed in a very recent article by Andrew Sheaff, having a higher bodyweight or a history of previous injury also raises your risk of sustaining an RRI in the future.

Can you test for YOUR risk?

The factors above provide a broad brush overview of whether you fall into the generally categories of runners who are at increased risk of an RRI. But while helpful, it doesn’t provide information on YOU. What might be particularly helpful is some kind of screening procedure to see if you have certain biomechanical traits or muscle function deficits/weaknesses that are specifically associated with an increased risk of a running-related injury. The good news is that some brand new research by a team of US researchers points a way forward, providing runners with a basic self screening test to provide a more accurate picture of their injury risk(7).

New research

In this study, which was published in the ‘Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine’ researchers from the Department of Orthopaedics, University of Utah set out to identify strength and flexibility measures that are associated with the risk of running-related overuse injuries in recreational runners. To do this, 867 runners registered for the 2019 New York City Marathon were recruited into the study. In the first stage of the study, all the runners were asked to complete a baseline strength and flexibility self-assessment 16 weeks before the marathon date. Following this baseline assessment, the participants were asked to respond to surveys on any running-related injuries they had suffered occurring within four different 4-week ‘training quarters’, which took place at 16, 8, 4, and 1 week(s) before the actual marathon race (November 3rd 2019).Following the race, the researchers pooled all the data and looked for correlations between key measures of baseline strength and the rate of subsequent injuries while training for the marathon.

What did they find?

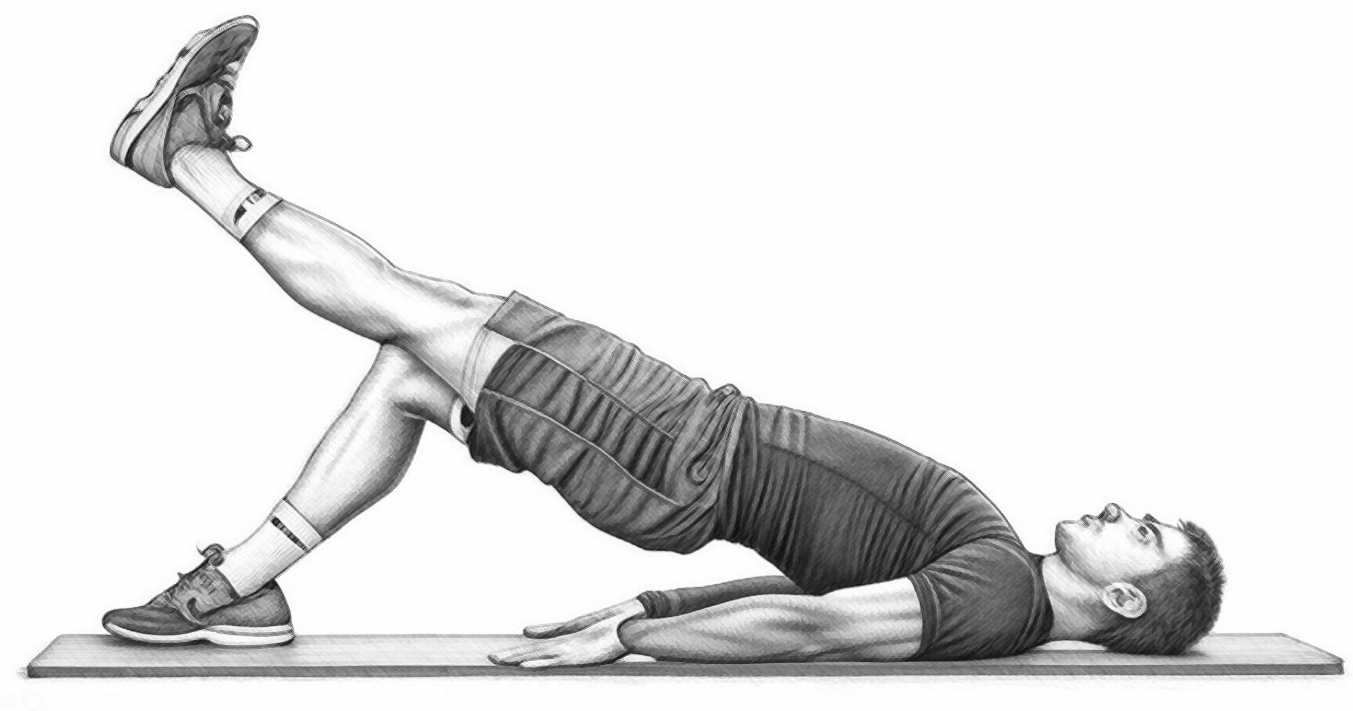

When the data was analyzed, it showed that 36.1% of the runners had sustained a running-related overuse injury while preparing for the marathon during the observation period – a high proportion given this period was just 16 weeks long! When the researchers looked for correlations between strength and flexibility scores and subsequent injury risk, there seemed to be no link with flexibility and injury risk. Many of the strength scores also seemed to be unrelated to injury risk. However, one strength exercise showed a remarkably high correlation – the single-leg glute bridge (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The single-leg glute bridge exercise

Participants who reported that they could hold a single-leg glute bridge on their weaker (non-dominant) side for 20 to 29 seconds had a 64% lower risk of sustaining a running-related overuse injury than those who could only hold the exercise for 0 to 9 seconds on their weaker side. In addition, participants who reported that they could hold a single-leg glute bridge on their weaker side for over 30 seconds had a 49% lower risk of sustaining a running-related overuse injury compared to the average risk in the runners overall! When summing up their findings, the authors concluded that strength training programs particularly those that target the glute muscles of the buttocks, hip abductors and related muscle groups, may provide injury-prevention benefits for distance runners.

Applying the knowledge

The risk of a running-related injury is multifactorial, which makes it hard to predict. This of course is self evident because if injury risk could be accurately predicted, runners could intervene beforehand and there would be virtually no running injuries! What this study provides however is a simple test, which, along with other factors, can help further identify those runners at particular risk. Perhaps more importantly, the findings also suggest that muscle weakness identified in the test (glutes and hip abductors) could itself be a major risk factor – and conversely, that strengthening these muscles could significantly reduce the risk of injury.

As the researchers commented, one simple practical application for recreational runners would be to periodically carry out this test to evaluate single-leg glute bridge strength. As a very minimum, you should be able to maintain this position for at least 20 seconds on your weakest side. If you can hold the position for more than 30 seconds, that’s even better. Practicing this exercise itself is one way to help develop that strength, but there are a variety of exercises that you can use to further train and strengthen these muscles. For beginners and those unfamiliar with how to train and strengthen the glutes and hips, the video below by ‘WeShape’ is well worth a watch. It provides an excellent introductory guide, and the exercises can all be performed at home!

References

1. Sports Health. 2020;12(3):296-303

2. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(8):469-480

3. J Sport Health Sci. 2021;10(5):513-522

4. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(14):887-892

5. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(8):450-457

6. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2025 Jan;35(1):e70004

7. Clin J Sport Med. 2025 May 23. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000001370. Online ahead of print

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.