Running injuries: hip strength symmetry for foot health

SPB looks at new research on the link between hip strength asymmetry and a greatly increased risk of debilitating condition in runners known as plantar fasciitis

It’s perhaps not surprising that running is one of the most accessible and widespread forms of physical exercise globally. It produces high levels of aerobic fitness in a time-efficient manner, offers substantial health advantages such as lowered cardiovascular risk, it can be done anytime, anywhere, and it only requires a minimal outlay for equipment. However, there is a downside for runners, especially who train and compete recreationally or at the amateur level, and that is the risk of picking up a running-related injury (RRI).

The dreaded ‘I’ word

Despite running’s benefits, there’s a definite downside for those who run as their main sport – injury. Numerous studies show that running is associated with a notable incidence of running-related injuries (RRIs). For example, in any 12-month period, previous research has shown that lower extremity RRIs occur in an estimated 50% or so of recreational runners, with some studies suggesting this to be even higher(1-3). And in a study published last year, data showed that RRIs will affect up to 69.8% of runners at some point(4).

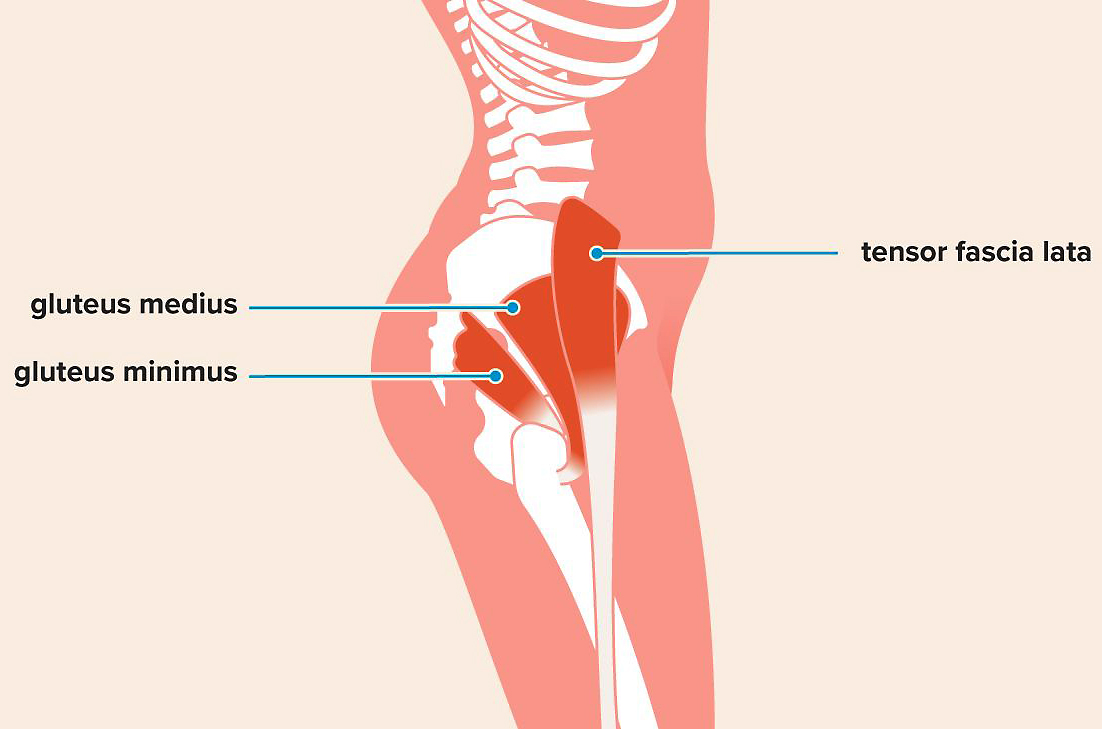

Common sites of injury include the knee and foot, with conditions like patellofemoral (knee) pain, iliotibial band syndrome, and plantar fasciitis (PF, which produces pain and soreness in the heel and base of the foot – see figure 1) being prevalent. Plantar fasciitis (which we’re going to look at in this article) occurs as a result of chronic degeneration of the plantar fascia due to repetitive mechanical loading and overuse, and manifests primarily as heel pain, particularly upon initial weight-bearing after rest(5). A review on RRIs found that PF ranks as the third most frequent RRI in runners (after knee and Achilles injuries), with an incidence of about 7.9%(6).

Figure 1: The plantar fascia and area affected by plantar fasciitis

Given that when injury strikes, even the best training plans and personal goals can go out of the window, so it’s very important to understand the risk factors that can precipitate an RRI so that the likelihood of injury is reduced as much as possible. Previous research has identified a number of RRI risk in runners, including:

· A sudden increase in training volume or intensity.

· A change of running surface.

· Incorrect shoe selection.

· Intrinsic biomechanical imbalances.

· Being an inexperienced, novice or overweight runner

Focusing in on PF injury, data reveals that excess body weight (a BMI of over 25) elevates the risk of PF by 1.4 times compared to normal weight BMI individuals(7), while foot structure also plays a role, with for instance, high-arched feet correlating with increased PF risk(8). In addition, biomechanical issues, such as excessive pronation can heighten plantar fascia tension and compress the fat pad, while high impact forces during running – for example during downhill running - further contribute to injury risk(9).

Asymmetry and PF injury

More recently scientists investigating the causes of RRIs – including PF - have turned their attention to asymmetries in lower limb strength as a potential factor(10). The cyclic nature of running means one limb tends to endure a disproportionate stress/loading if asymmetries exist, which amplifies the risk of injury on the weaker or overloaded side(11). In distance running, fatigue can also exacerbate any existing milder asymmetries, especially when running distances exceed 10km(12). The theory is that muscle strength imbalance may potentially affect motor control, resulting in impaired movement and coordination patterns, leading to a sub-optimal running gait. In short, muscle strength balance is crucial for optimizing movement patterns(13).

However, while it’s generally accepted that limb strength asymmetries can increase the risk of an RRI, much of this research has been retrospective – ie looking backwards at prior incidence of injury and linking it with current limb strength asymmetries. While retrospective studies are great for showing associations, they are not as useful as prospective studies when trying to investigate causal mechanisms (see box 1). When it comes to PF injury specifically, there’s been little prospective research into lower limb strength asymmetries and PF injury risk in amateur distance runners, and none in male amateur marathon runners who seem to be particularly at risk of developing PF injury(14).

Box 1: Study design; retrospective vs. prospective

- Retrospective studies look backward, analyzing existing data or past records to explore links between exposures (eg risk factors) and outcomes (eg diseases). They rely on historical information, like medical records or participant recall, making them quick and cost-effective but prone to inaccuracies.

- Prospective studies on the other hand track participants forward from a starting point, collecting data as events unfold. Researchers enrol subjects (eg healthy runners), monitor them over time, and record outcomes as they occur – eg the occurrence of injuries. Retrospective goes from outcome to exposure and uses past data, while prospective goes from exposure to outcome and gathers new data over time.

Prospective studies are more scientifically valid because they are generally more robust - due to reduced bias and stronger causal inference. They minimize recall bias, because data is collected before outcomes, avoiding faulty memory common in retrospective studies (eg athletes misreporting past training behaviors). They also better control extraneous variables by measuring them systematically from the start, unlike retrospective studies, which may miss key factors in old records. Additionally, prospective designs establish temporality, clearly showing that exposures precede outcomes, a critical factor for establishing causality. Their structured data collection also enhances accuracy and reliability. For confirming cause-and-effect therefore, prospective studies are preferred due to their rigor and reduced bias.

New research

To investigate the link between limb strength asymmetry and the risk of PF injury, a team of Chinese researchers has carried out a study, which has just been published in the journal ‘BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation’(15). This prospective cohort study recruited 177 uninjured male amateur marathon runners aged 18-30 from Beijing universities and running clubs in October 2023 via social platforms like WeChat. Inclusion criteria required a weekly running mileage of at least 10km and at least one marathon completed in the prior year, with no injuries in the preceding three months.

To begin with, baseline data was collected from all the runners, which included age, height, weight, BMI, foot arch type (assessed via the ‘wet footprint method’ and categorized as high, normal, or flat), training habits, injury history, and dominant leg. Strength was measured using a reliable MicroFet3 dynamometer for hip strength (flexion, abduction, rotation, extension), knee flexion/extension (hamstring and quadriceps strength), and ankle strength (plantar/dorsiflexion) movements. The tests required the runners to make three maximal efforts on both left and right limbs. Peak forces were recorded in each test and normalized to body weight. The left-right asymmetry was calculated as the difference between dominant (stronger) and non-dominant (weaker) sides. Following this, monthly follow-ups over three months tracked the runners’ training (mileage, resistance exercises) and the incidence of PF injury, diagnosed by heel pain worsening after inactivity, a positive ‘windlass test’, and disruption of training for over a week. New cases of PF were counted only if diagnosed by an expert, and were definitely related to running (ie no other injury cause).

The findings

Out of the 177 runners, 172 completed the study and were analyzed. Twelve runners (7%) developed PF, mostly on the dominant side. No differences were found in age, height, weight, or BMI, but the PF injured runners tended to run less than their uninjured counterparts (averaging 76.4km per month vs. 108.7km per month). The crucial finding however was that hip abduction (where the leg moves away from the midline of the body) strength asymmetry was much higher in injured runners, and this hip asymmetry significantly predicted PF injury risk. In fact the link was so strong that runners who had a left-right hip abduction strength asymmetry of 32.5% or more had triple (in fact 3.646 times greater) the risk of developing PF!

Implications for runners

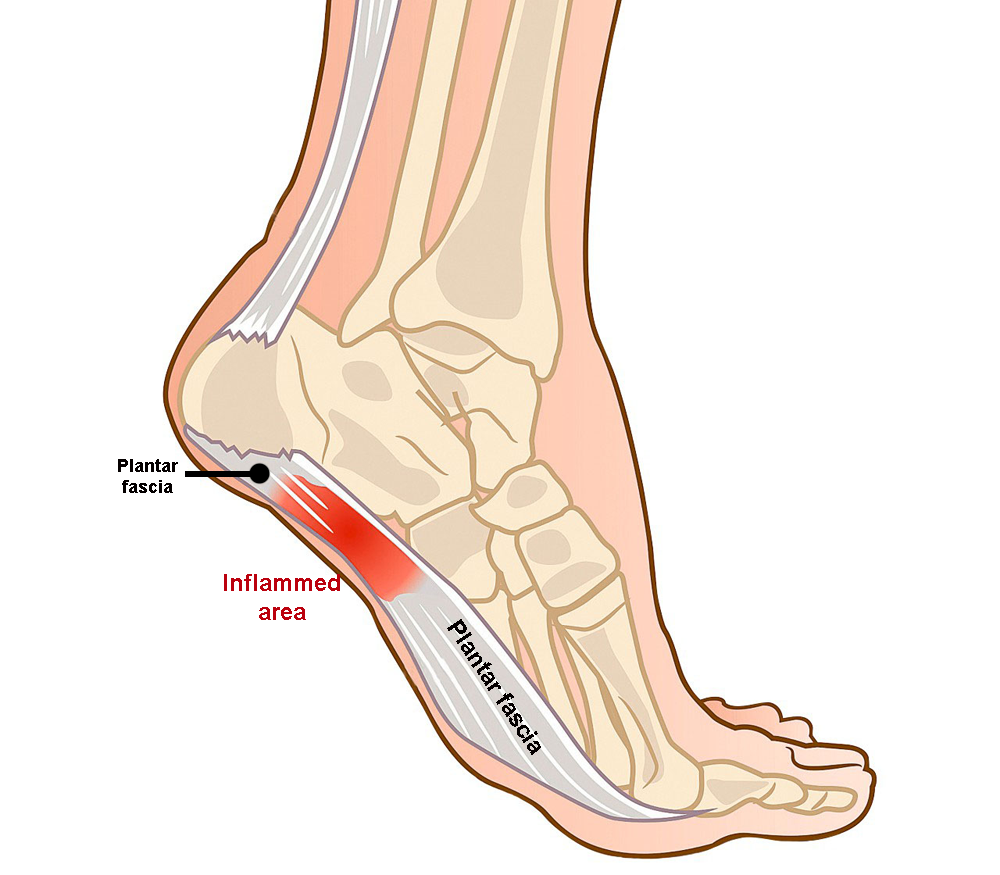

The key finding was that hip abduction asymmetry of 32.5% or higher triples the risk of a PF injury. This asymmetry means that the muscles around the hip that carry out abduction (gluteus medius and minimus, and tensor fasciae latae – see figure 2) are significantly weaker on one side compared to the other. This causes pelvic instability, which is transmitted through the kinetic chain down to the foot, which in turn increases stress on the plantar fascia during running(16). Interestingly however, most of the PF cases in this study occurred on the stronger, dominant side rather than the weaker side. This suggests that in compensating for weaker hip abductors on one side, runners tend to alter their gait so that the stronger side does more work, which eventually leads to a PF overuse injury on that side.

Figure 2: Principle hip abductor muscles

The main take-home message for runners who have either suffered a PF injury in the past, are trying to rehab a PF injury or who simply wish to avoid one in the future is that hip strength asymmetry is something that needs to be addressed. The good news is that testing for asymmetry and then strengthening the weaker hip abductor side is quite straightforward. Hip abductor strength asymmetry is almost always associated with a pelvis that is laterally tilted - ie looking from the front, one crest of the pelvis will be slightly higher than the other.

This can be checked by simply feeling for the crest of the pelvis on both sides with your fingers and observing in the mirror. If there is an imbalance, the weaker hip abductor muscles will be on the same side where the crest of the pelvis is higher. See the video below for an excellent tutorial on how to assess whether you have a significant lateral pelvic tilt present, and if so how to address it by stretching the quadratus lumborum muscles and strengthening the hip abducting glute muscles.

Another way of checking hip abductor strength asymmetry is to carry out hip abductor strengthening exercises on both hips; if you struggle to complete as many reps on one side as the other (falling short by 10% or more), that’s almost certainly your weaker side. The next video below by Physio Fit Health (physiofithealth.com.au) shows some great exercises that can serve as both screening and strengthening exercises to help you eliminate significant asymmetries.

References

1. Sports Health. 2020;12(3):296-303

2. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(8):469-480

3. J Sport Health Sci. 2021;10(5):513-522

4. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2024;54(2):133–41

5. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;46(6):442–6

6. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2010;39(5):227–31

7. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(9):996–9

8. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(11):1159–65

9. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(12):3072–80

10. Foot (Edinb). 2020;42:101636

11. J Biomech. 2006;39(15):2792–7

12. Sports Med Open. 2020;6(1):39

13. China Sport Sci Technol. 2023;59(3):28–36

14. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(2):95–101

15. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2025 Aug 28;17(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s13102-025-01295-z

16. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):42–51

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.