You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Supplements for recovery: is creatine up to the job?

SPB looks at new research on creatine and investigates whether it could help you recover faster during periods of intense training and competition?

When it comes to sports nutrition, I am minded of a phrase often used by my very wise coach and mentor of many years ago. He used to say “Andrew, when it comes to sports nutrition, there are lies, damned lies and sports supplements.” While this sounded a bit cynical at the time, I gradually came to understand how much truth there was in what he said. The fact is, that when all the hype is stripped away and sports supplements are subjected to rigorous scientific testing, there are actually very few supplements that have consistently been shown to safely and legally improve performance. For endurance athletes, caffeine is a great example of a safe and legal supplement that is proven to enhance performance in the real world. However, for athletes who require strength, power, speed and mental acuity, another supplement that does exactly what it says on the tin is creatine.

Creatine research

Because creatine is so effective, it’s also one of the most widely studied sports supplements, and a topic that we have covered extensively in SPB (see these articles). Indeed, review studies that have gathered together all the prior research into creatine and athletic performance have concluded that creatine supplementation can benefit both high-intensity (anaerobic) and lower intensity (aerobic) performance, as well as boosting strength and muscle mass, especially in older athletes(1).

More recently, SPB contributor Andrew Sheaff highlighted very recent research from December 2025 on how athletes can best use creatine to optimize its positive impact on their performance (see this article)(2). One of the findings to emerge from this research was that creatine may positively impact recovery via reduced muscle protein breakdown rates – ie that part of the reason creatine is effective may be that it limits the amount of muscle protein breakdown following training. The research also hinted that - related to this - creatine may be able to speed up recovery following injury, surgery and/or immobilization, although this has only been clearly shown in animal models.

Creatine for recovery

Hot on the heels of the research highlighted above by Andrew, a new study by an international team of scientists has investigated whether a short-term period of creatine ingestion can indeed help accelerate recovery in trained strength athletes(3). Published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, the researchers investigated whether an initial dose of creatine followed by a further three days of supplementation was able to accelerate recovery and improve performance across repeated resistance-training sessions in trained males, reduce markers of fatigue during this period and accelerate recovery from lower-limb strength and soreness.

Study details

To carry out this study, 11 strength-trained athletes were recruited, ten of whom completed the study and whose data was analyzed. Using well resistance-trained athletes who were already accustomed to high-intensity lifting is especially relevant here because trained athletes often have less room for improvement than beginners, so any significant gains observed are more noteworthy – and likely applicable to other strength athletes. Importantly, this study also used a rigorous ‘double-blind, randomized, crossover design’. Basically, this meant that both the participants and the researchers were blind to who was taking the supplement or a placebo in each trial to avoid possible bias creeping in. And because every participant completed both the creatine and placebo phases of the study, each subject could serve as his own ‘control’, thus reducing the inter-individual variability factor.

What they did

All the participants completed two identical trials on two separate occasions, with at least seven days between the two trials. Each trial consisted of the following:

· Bench press (BP) and back squat (BS) tests performed at 60%, 70%, and 80% of one-repetition maximum (1RM).

· Strength performance tests (number of repetitions, movement velocity, and peak power).

· Jump tests consisting of countermovement jump (CMJ) and squat jump (SJ).

· Monitoring of peak heart rates, heart rate variability (HRV - a measure of fatigue/recovery, with higher levels of HRV indicating less physiological fatigue) and delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS).

The only difference between the two trials was what the participants consumed two hours before each trial and for the next 72 hours afterwards:

· Creatine trial - Participants ingested either 900mls of fluid containing creatine monohydrate (0.3g·per kilo of bodyweight per day), with the first day’s dose consumed two hours before the trial, and subsequent doses for the next three days divided into 3 x daily doses each does being 0.1g per kilo (totalling 0.3g per kilo per day).

· Placebo trial – exactly as above but without any added the creatine in the fluid.

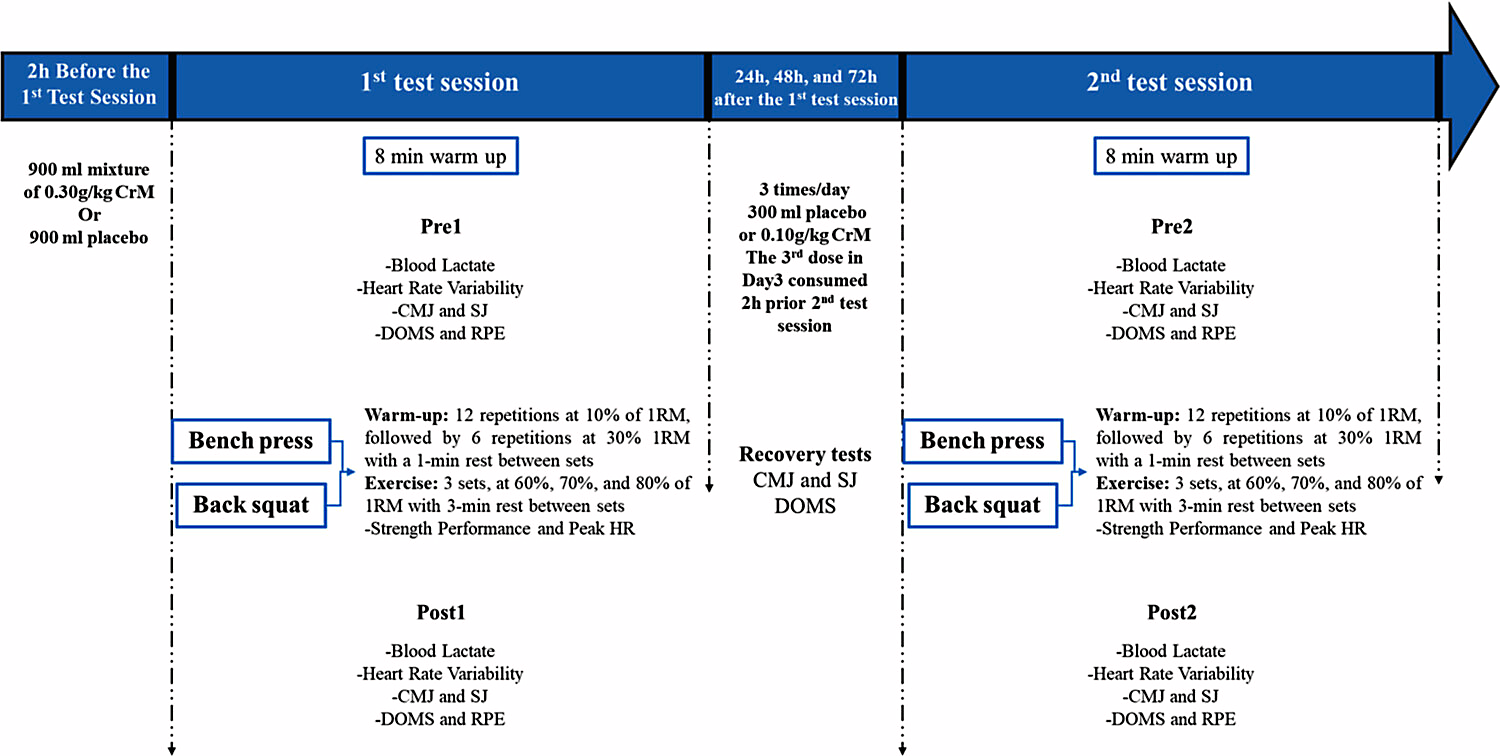

As mentioned above, the order of the two trials was randomized for the athletes and neither the athletes nor the researchers knew which was being taken in either of the two trials. The overall experimental protocol is summed up in figure 1 below. In order to increase the validity of the findings, all the participants were instructed to refrain from food or drink (except water) two hours before testing and avoid other supplements on non-testing days. Adherence was tracked via a compliance log. In addition, the athletes were instructed to avoid creatine-rich foods, stimulants, gum, sweets, and alcohol for three days before testing; stay adequately hydrated; avoid strenuous exercise during the study period; and sleep at least eight hours per night.

Figure 1: Study and testing protocol

Key to abbreviations: CrM: Creatine monohydrate; 1RM: One Repetition Maximum; Pre1: Before the 1st session; Post1: After the 1st session; Pre2: Before the 2nd session; Post2: After the 2nd session; HR: Heart rate; CMJ: Countermovement jump; SJ: Squat jump; DOMS: delayed onset of muscle soreness; RPE: Rating of perceived exertion.

What they found

When the data was collected and analyzed, the researchers divided their findings into three broad categories: strength and power output, cardiovascular/neurological responses and recovery, physical and subjective recovery. Here is what they found:

· Strength/power: in the creatine trial, the athletes completed significantly more repetitions at all weight intensities (60-80% 1RM) for both the bench press and the back squat compared to when they took placebo. Moreover, measures of velocity of reps showed that when taking creatine, the athletes moved the weights faster across all sessions. In plain English, this faster velocity translates to increased power generation and the ability to maintain high-speed explosive movements even as the sets got harder.

· Cardiovascular/neurological responses: when the athletes took creatine, there appeared to be less ‘cardiovascular strain’. For example, when back squatting at 60% 1RM intensity, the athletes maintained a lower heart rate in the creatine trial than in the placebo trial. In addition, the results showed that when the athletes took creatine, they had enhanced ‘parasympathetic reactivation’ after exercise. In short, this meant that their bodies were able to ‘switch back’ into a recovery state much more rapidly after the stress of lifting if they were consuming creatine.

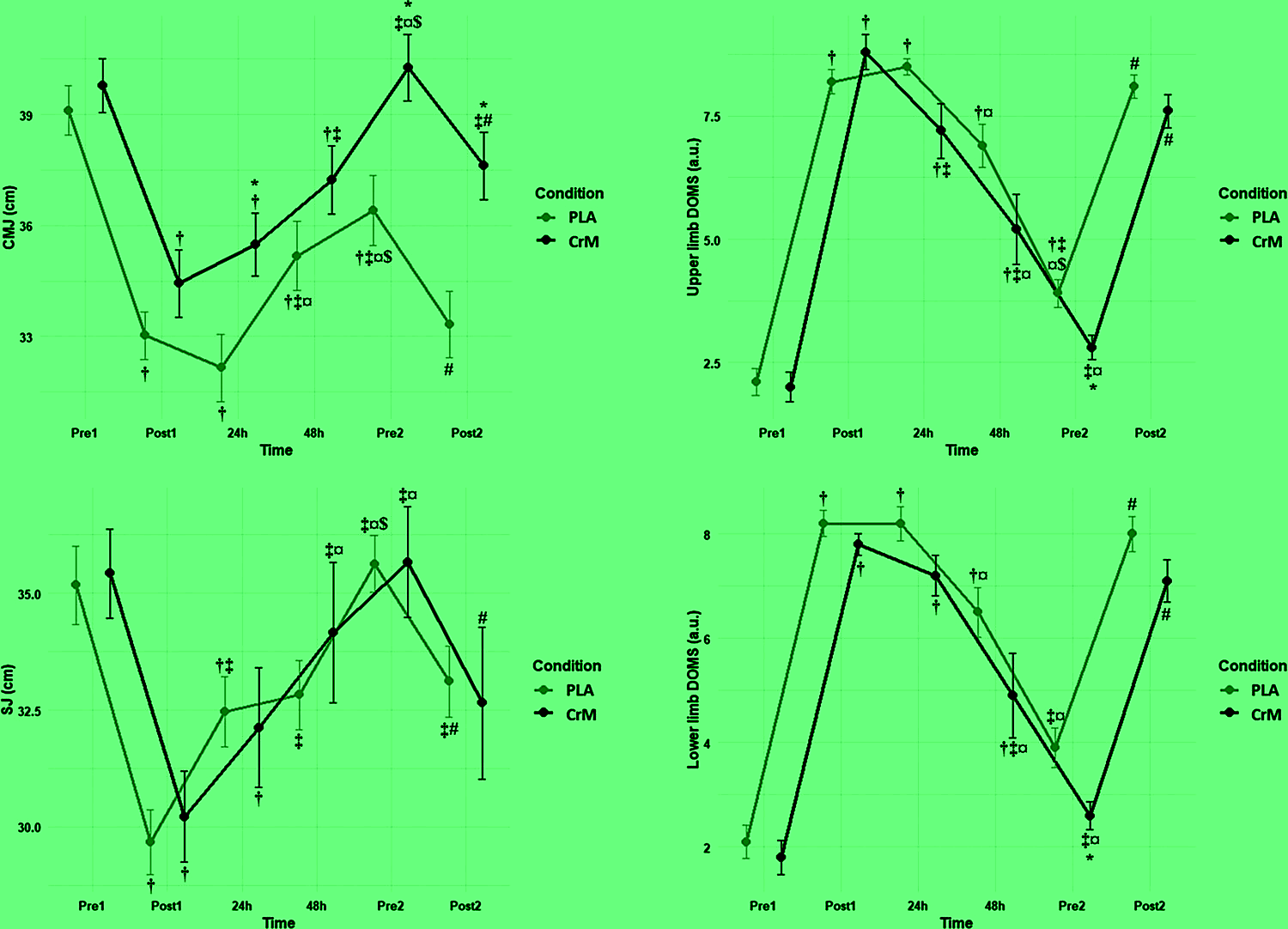

· Physical and subjective recovery: when the athletes took creatine, they maintained better countermovement jump performance 24 hours after the first intense lifting session, indicating that their ability to develop explosive power had recovered more rapidly compared to when they took the placebo (see figure 2). Not only that, but the athletes also reported significantly reduced muscle soreness in both their upper and lower bodies 24 to 48 hours after the initial training bout (figure 2).

Figure 2: Physical and subjective recovery with and without creatine

Countermovement jump (CMJ), squat jump (SJ), and delayed onset of muscle damage (DOMS) recorded pre- and post-1st sessions, 24 h, 48 h, and pre- and post-2nd session for creatine monohydrate (CrM) and placebo (PLA) conditions. The athletes performed better post-training in the countermovement jump (top left) when taking creatine and suffered less DOMS (upper and lower right).

Practical implications

The key take-home message from this new research is that creatine ingestion doesn’t just enhance strength and power (we already knew that) but that a short-term, high-dose regimen of creatine supplementation can also help recovery. Therefore, if you are about to undertake a particularly onerous week of training (eg by attending a pre-season training camp), or if you face the prospect of a multi-day competition (eg back –to-back soccer matches or rounds of a competition), three days of creatine ingestion could help you recover faster from your initial efforts and perform better in subsequent bouts of competition or matches.

While the usual recommendation for athletes seeking to benefit from creatine ingestion is to take 3-5 grams of creatine daily for 30 days, or to take 20 grams per day for seven days (to saturate muscles), the research above suggests that following an initial dose of 0.3 grams per kilo of bodyweight (preferably before your first exercise bout), then taking 0.1 grams per kilo three times a day for the next three days will result in real recovery benefits. So for example, if you weigh 80kgs, you would take an initial dose of 80 x 0.3g = 24 grams then follow up with three daily doses of 8 grams for the next three days.

By doing this, the evidence suggests that you will likely recover physically more rapidly, suffer from less muscle soreness and be better able to undertake more workload and generate higher levels of power and speed over those three days. Remember too that this short-term protocol may also help your heart and nervous system allowing them to ‘bounce back’ more rapidly after initial fatigue, which in turn can help prevent the accumulation of ‘neurological tiredness’, thus reducing the risk of overtraining.

For those with sensitive tummies, splitting your daily total creatine intake into three or four doses is recommended. To reduce the risk of gastric distress, take the creatine after a meal rather than on an empty stomach. Bear in mind too that you’ll need to drink extra water as creatine absorbed into muscles also draws water into the muscle cells. For that reason, you should expect to temporarily gain a pound or two, but remember that this extra weight is just water and will be lost during subsequent exercise bouts. Finally, forget taking fancy forms of creatine; plain old creatine monohydrate is just fine for doing the job. However, make sure you purchase it from a reputable manufacturer who is guaranteed to meet high standards of purity!

References

1. Cureus. 2023 Sep 15;15(9):e45282

2. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2025 Dec;22(1):2441760

3. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2025 Sep 30;22(sup1):2617283. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2026.2617283. Epub 2026 Jan 24

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.