Interval training: once, twice or thrice per week?

SPB looks at new research on how the frequency of interval training affects the performance gains that amateur athletes can expect

Distilled down to the very basics, ‘interval training’ is a method of training that intersperses intervals of high-intensity exercise, with short periods of rest. Why has this type of training become so popular among elite sportsmen and women? The answer is easy; done right, interval training allows you to get bigger fitness gains, faster than simply ploughing along endlessly at a steady intensity. The popularity of interval training is not based on hearsay but rather on a large body of empirical evidence showing that performing regular bouts of high-intensity interval training is an extremely effective training tool for athletes seeking to maximize performance for a relatively low training workload(1). Put simply, short sessions of high-intensity intervals are a great way of producing gains in aerobic power, enabling an athlete to sustain a higher intensity/pace/workload for longer before fatigue sets in.

The perfect interval recipe

What’s less clear however is how to put together an interval program to deliver the greatest performance gains per unit of time and effort invested. That’s hardly surprising as there are so many variables to consider. Overall, scientists have determined that there are six factors determining the overall ‘recipe’ for interval training. These are(2,3):

-Total workload of a session

-Duration of each interval

-Interval intensity

-Recovery duration

-Recovery type (ie active or passive)

-Total interval training time per week

Depending on the purpose of the training session, these variables can be manipulated to give countless different combinations. Studies of well-trained endurance athletes indicate that the best training effect, i.e., increased stroke volume and oxygen delivery, is achieved at intensities between 85%–95% of maximum heart rate(4,5), although studies have also demonstrated positive effects of training at even higher intensities(6).

Interval session frequency

While there’s a lot of data about the fitness and performance benefits of different interval training regimes, one thing that’s far less clear is how best athletes can integrate their interval training into their weekly endurance training program. In particular, there’s still a lot of debate about the optimum number of interval training sessions per week needed in order to maximally stimulate training adaptations. Retrospective data collected from world-class endurance athletes shows that they typically perform one or two three interval sessions per week, often along with another type of high-intensity session (eg a short but maximal session)(7). The problem of course is that most athletes who enjoy training and competing are not elite world-class athletes, but rather recreational, weekend warrior or keen amateurs competing at club level.

It’s known that altering the frequency of interval sessions can significantly influence the overall training outcomes – not just in terms of adaptation and performance improvements, but the degree of recovery that athletes can expect(8,9). However, the data is very mixed; some studies have shown that interval training regimens performed once or twice weekly are not particularly effective for enhancing cardiorespiratory adaptation, specifically in terms of improving maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max)(10). However, other research shows that two interval sessions per week is effective at improving cardiorespiratory fitness, and that adding a third session per week can further improve it(11).

Answering the question

The question remains therefore: how frequently should athletes, particularly non-elite athletes, perform interval sessions each week to get the best bang for buck? Too few sessions might not lead to significant gains. However, too many sessions may well risk burnout or injury. What’s needed is some data on recreational athletes undertaking different frequencies of interval sessions, and now a brand new study by a team of German scientists has provided a useful insight(12). Published in the journal Physiological Reports, this study set out to investigate how different frequencies of interval sessions affect cardiorespiratory fitness such as maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max), metabolic markers (eg blood lactate and glucose), and running performance (such as time-to-exhaustion and running economy) in recreational runners. The answer to this question is critical for both runners and coaches; interval sessions need to be prescribed in a way that maximizes gains while fitting into a training schedule, and which doesn’t lead to exhaustion of injury down the line!

What they did

The researchers investigated how performing intervals either once, twice, or three times per week affected the performance of recreational runners, and if so, what the differences were between the different training schedules. To do this, 26 recreational runners, aged 18–50 were recruited. All of the runners were already running at least three times per week with a total weekly mileage of around 10-40 miles per week. The participants were then randomized into three different training groups. These were as follows:

- Group 1: One regular run was replaced with one interval session per week. This session consisted of 4 x 4-minute efforts performed at around 90–95% of max heart rate (HRmax), with 3-minute active recovery periods at 60–70% HRmax in between each effort.

- Group 2: As above, but with two regular runs replaced by two interval sessions per week following the format as above.

- Group 3: As above, but with three regular runs replaced by three interval sessions per week following the format as above.

All three groups followed this intervention for a period of six weeks, keeping total weekly running volumes and other workouts consistent. The substitution of regular runs in a training schedule for interval sessions was used by the researchers because it mimics the approach that many athletes use in practice - swapping out an easier run for a high-intensity session in order to add an extra training stimulus - without overhauling the whole plan.

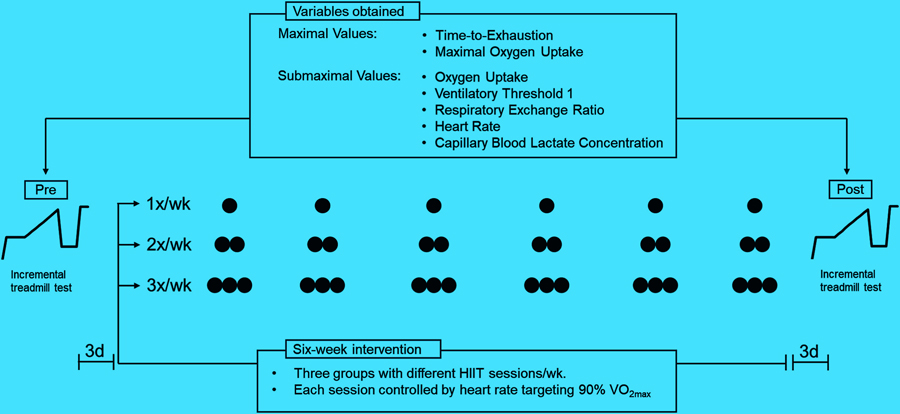

Before and after the six-week intervention (see figure 1), all the runners underwent testing, which included the following:

· VO2max assessment using an incremental treadmill test (to measure maximal aerobic capacity - an important metric of endurance performance).

· Time-to-exhaustion testing, where the runners ran at a fixed speed until they couldn’t maintain that speed anymore.

· Running economy testing, which measured how efficiently the runners used oxygen to cover a given distance while running at a submaximal pace.

· Metabolic markers, including blood lactate and glucose levels during exercise to assess metabolic stress and efficiency.

· Body composition, including fat mass, lean mass, and body weight (measure with via bioelectrical impedance).

After the 6-week intervention the changes in the above parameters were compared for the three groups to see how the different frequencies of interval sessions had impacted fitness and performance.

Figure 1: Protocol of the 6-week intervention and before/after testing

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

- Out of the targeted 6, 12, and 18 sessions for the 1 x weekly, 2 x weekly, and 3 x weekly groups, the participants achieved adherence rates of 100%, 96%, and 91%, respectively. This shows that all three programs were managed well by the athletes, although performing three interval sessions per week proved a little harder to stick to.

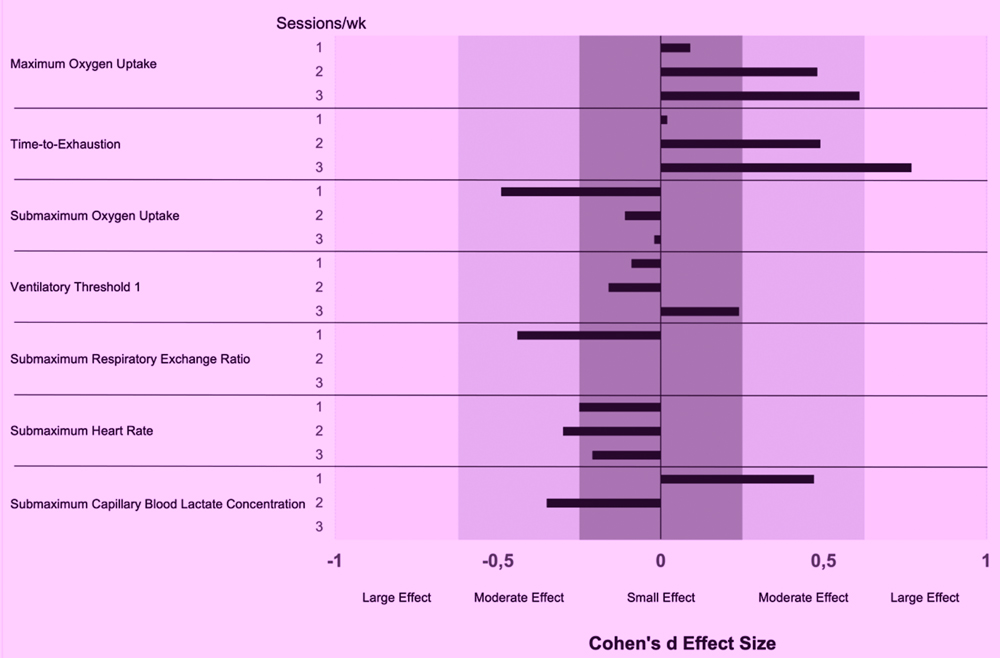

- When the data was analyzed statistically, the ‘effect size’ for pre- to post-intervention for changes in VO2max and submaximal heart rate (see figure 2) in participants training two or three times per week was considered moderate to large.

- The effect size for one session of intervals per week was considered small (though still meaningful). [NB - effect size measures the strength of a relationship or the magnitude of a difference between groups and is sometimes used to measure a trend following an intervention where the study size is small.]

- All groups improved their time to exhaustion (TTE), but the three-session group had a notably superior response over the two-session group while the one session group made only small gains.

- There were no significant before/after differences in running economy between the groups. The same was true for measures of body composition.

- The individual responses within the 1, 2 and 3 session per week groups were quite variable, suggesting that while two and three interval sessions per week proved more effective overall than one session, there’s no ‘one size fits all’ to program prescription.

Figure 2: Pre-post intervention effect sizes for 1/2/3 interval sessions per week

Practical advice for athletes

In their summing up, the authors concluded as follows: ‘our exploratory study suggests that two or three weekly sessions of 4 x 4-minute intervals may be effective for improving VO2max and time to exhaustion in recreationally active individuals. There is no clear additional benefit from increasing the frequency to three sessions per week; these preliminary findings therefore support the potential value of twice-weekly interval training as a practical and time-efficient strategy for enhancing key endurance parameters’.

In plain English, this means that while one session per week of intervals still delivered endurance benefits, there were large additional benefits when two sessions per week were performed. Compared to twice a week intervals, three times a week produced some further performance gains, but these were only slight. Therefore the researchers concluded that twice per week interval sessions is likely the sweet spot when balancing time, effort and results. A twice-weekly interval program also has the benefit of being easier to stick to than a thrice-weekly program, and is also less likely to result in injury or excessive fatigue.

That said, we should add some caveats. Firstly, while the 1 x session per week was the least effective approach, it still produced endurance fitness gains, and shouldn’t therefore be dismissed out of hand. Indeed, athletes who are performing a relatively high volume of training (eg marathon preparation) may find that one interval session per week is all that can be managed without becoming excessively tired. The same may be true for those who are unaccustomed to interval training or who are regularly performing other types of tough endurance sessions – eg hill sessions.

Secondly, a key finding was a large variability in individual responses to interval training. While two sessions per week seemed to be the sweet spot, you might be the type of athlete who recovers more slowly, making twice-weekly intervals a big ask, which means that you may make better progress with a single session per week. By contrast, if you have fast recovery (more likely for younger athletes!), you may find you can easily handle a third interval session per week and make even more progress. Remember too that your work capacity isn’t fixed. For example, during times of stress or sleep deprivation, that two x interval sessions per week may have to be temporarily reduced to one. As with any program, you should always listen to what your body is telling you. If it’s telling you to back off, you almost certainly need to!

References

1. Sports. 2015 Oct;45(10):1469-81

2. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 53–73

3. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 188–192

4. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1974–1980

5. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, 74–83

6. Sports Med. 1986, 3, 346–356

7. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 2548–2554

8. ) Sport Sciences for Health 2017. 13(1), 17–23

9. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2018. 39(3), 210–217

10. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2010. 31(8), 567–571

11. JAMA 2013. 310(20), 2191–2194

12. Physiol Rep. 2025 Sep;13(18):e70573. doi: 10.14814/phy2.70573

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.