You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength training: the long and short of eccentric reps

Andrew Sheaff looks at new research on how manipulating the eccentric or lowering phase of your reps when strength training can affect the benefits it delivers

Resistance training is a key aspect of improving performance across all sports. However, as with all training practices, the approach to resistance training and the optimal implementation of various resistance training methods has evolved over time. While it’s easy to recognize the importance of the lifting phase – more technically known as the ‘concentric’ phase, where muscle fibers shorten under load - it has became apparent that it isn’t just the lifting of a weight that influences training adaptations; how that resistance is lowered - known as the ‘eccentric’ phase, matters as well.

Manipulating eccentric contractions

Because of its importance, coaches, athletes and scientists have explored how to manipulate the eccentric phase in resistance training to optimize various training adaptations. One of the more obvious ways to do so is to change the speed of the eccentric phase. For example, it can be performed quickly, or even as fast as possible, or it can be performed slowly. As training practices changed, researchers have sought to document the impact of different durations of the eccentric phase. In these studies however, different study protocols and different phase durations have been used. Also, while a lot of research has been performed on strength training in general - and the eccentric phase in particular - there’s much less research specifically looking into the impact of the length of the eccentric phase. Therefore it has been difficult to properly understand the specific impact of eccentric phase duration due to these differences. The good news however is that a newly-published study has sought to bring clarity as to exactly how eccentric phase duration impacts the training adaptations that are of particular interest to athletes looking to enhance performance.

The research

The New Zealand researchers set out to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of eccentric phase duration on training outcomes(1). This was done by carrying out a systematic review and meta-analysis, where all the relevant previous research on this topic was analyzed and all the data from the studies pooled. To be included in this meta-analysis, the authors required any study to use the duration of the eccentric phase as an independent variable, or the variable that was being manipulated to influence an outcome. Specifically, the eccentric phase had to be classified as ‘shorter’ than two seconds or ‘longer’ than two seconds, with the 2-second point being the dividing marker. If the duration was listed as ‘as fast as possible’ it was also included in the ‘shorter’ category.

In addition to duration of the eccentric contraction, there were several other inclusion requirements for this meta-analysis:

- Studies needed to investigate improvements in muscular performance and/or hypertrophy.

- Both eccentric and concentric contractions were included in each repetition.

- The duration of the concentric contraction was controlled..

- The total rep volumes were controlled between groups.

- The studies lasted at least four weeks (to allow enough time for adaptation to occur).

Analyzing the data

Overall, nine experimental studies and one literature review met these criteria for inclusion. With the appropriate studies in hand, the researchers set about analyzing the data with several key objectives in mind. First up, they wanted to understand the impact of eccentric phase duration on maximal strength. Next, they wanted to understand the impact of eccentric phase duration on hypertrophy (muscle growth). Finally, they wanted to know how the duration of the eccentric phase affected countermovement jump performance. While all three of these measures are potential outcomes of resistance training interventions, it’s important to note that they are quite distinct, and the same training stimulus can impact each of the three differently.

For both the maximal strength and hypertrophy analyses, the researchers examined whether moderating variables influenced the outcome. The most important moderating variables were training status and study design. For training status, the authors differentiated between trained and untrained subjects. This is important because training responses can often differ between those who are trained vs. those who are untrained.

They also distinguished between two types of study design:

- One type of study compared responses in a group of participants, where some used short eccentric phases and others used long eccentric phases.

- Another type of study compared the phase durations within subjects. For instance, the subjects would perform short eccentric phases on the left side of their body and long eccentric phases on the right side of the body.

Both training status and study design can be impactful, so it’s important to tease out these effects.

What they found

When the results were tallied, the researchers found that maximal strength was NOT likely to be influenced by eccentric phase duration (see figure 1). However, the statistics involved in the analysis involved probabilities rather than certainties, so the authors concluded that long eccentric phases do ‘not practically harm maximal strength gains in these subgroups, but whether it enhances maximal strength gains by a practically worthwhile degree cannot be inferred with certainty.’ This is a rather long-winded way of saying that longer eccentric phases definitely don’t hurt strength improvements and may help them.

The results were similar for hypertrophy. There was a non-statistically significant favorable advantage for longer eccentric phase durations (meaning that the advantage was not big enough to rule out that it might have occurred due to a statistical blip rather than a real effect). In plain English, this means that while we can’t be certain that longer eccentric phase durations help enhance hypertrophy outcomes, they may do, and we know for sure that they definitely don’t harm hypertrophy outcomes.

In contrast to the maximal strength and muscle hypertrophy findings, there was a strong finding in favor of short eccentric phase durations for counter movement jump (see figure 2). Shorter eccentric phase durations led to larger changes (improvements) in countermovement jump performances. Finally, for all three variables, moderator effects such as training status and study design had no effect on outcomes.

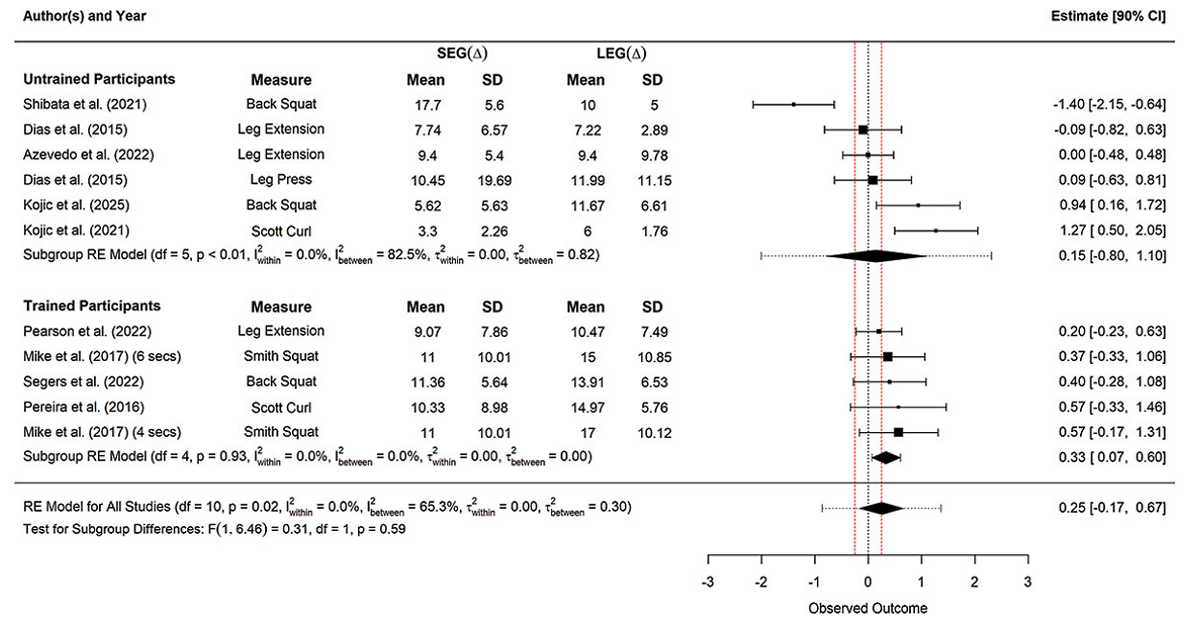

Figure 1: Maximal strength and eccentric rep duration

In this ‘forest plot’, the individual squares represent a study finding, and the three diamonds top to bottom represent the average of the studies for untrained, trained and both combined respectively. Squares and diamonds to the right of the zero line represent a potential benefit for longer eccentric durations and to the right of the right hand red dotted line represent a real benefit. While the diamonds lie mostly to right of the zero line, they do not lie to the right of the right-hand red line. This means while there is a trend towards a beneficial effect for longer duration eccentric reps, we cannot be confident the effect is significant.

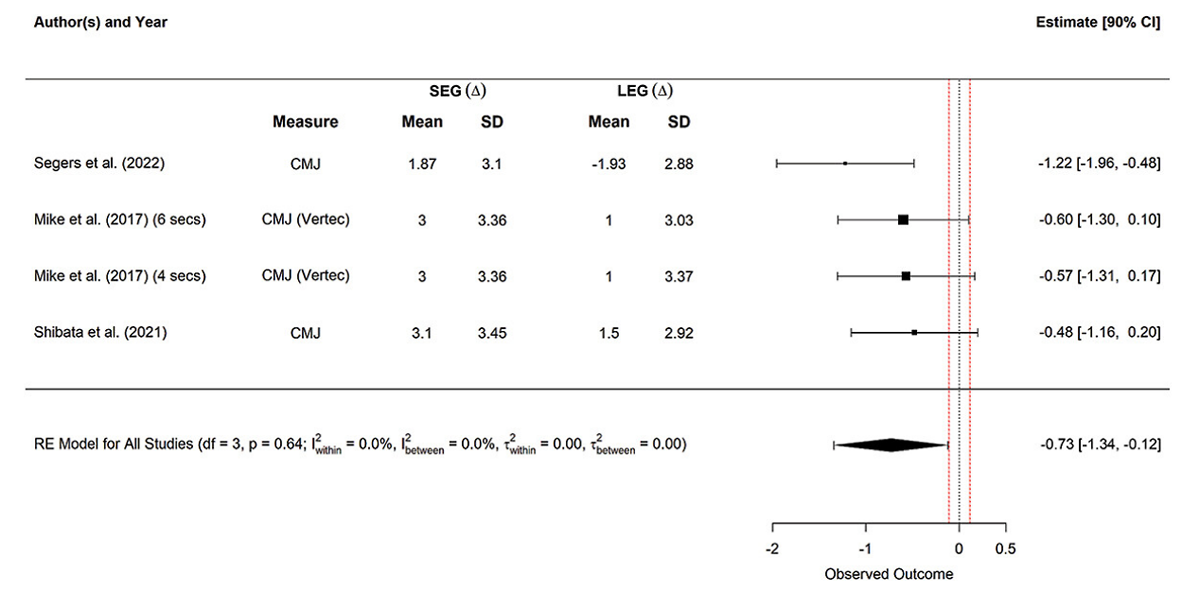

Figure 2: Countermovement jump performance and eccentric rep duration

In this forest plot, the individual squares represent a study finding, and bottom diamond represents the average of the studies. Squares and diamonds to the left of the zero line represent a potential benefit for shorter eccentric durations and to the left of the right hand red dotted line represent a real benefit. Here the diamond lies entirely to left of the zero line, indicating a significant beneficial effect for shorter than 2-second eccentric reps when targeting countermovement jump and explosive performance.

Practical recommendations for athletes

When it comes to optimizing improvements in maximal strength, muscle hypertrophy, and countermovement jump, there are several takeaways from this study. First, if the goal is to improve countermovement jump, shorter eccentric phase durations are definitely the way to go. Keep your eccentric contractions (the phase where the resistance is lowered) at less than two seconds. While the study didn’t investigate whether shorter is better within that window, the possibility is something to consider.

For optimizing muscle hypertrophy and maximal strength, it appears that either approach can work. However, there is the possibility that longer eccentric phase durations could be beneficial, and they certainly aren’t worse. If your priority is achieving these two outcomes, emphasizing longer eccentric durations (than two seconds) makes sense. Overall, the decision to emphasize shorter or loner durations should depend on your goals. Choose shorter durations if jumping or explosive performance is the goal. Consider longer durations when strength and hypertrophy are the goal. And if you are working toward improvements in all three, a mixed approach is likely to be most beneficial.

References

1. Sports Sci. 2025 Jul 21:1-18. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2025.2535198. Online ahead of print

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.