You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength training loading: do all roads lead to Rome?

Is it mandatory to use high-load strength training to develop maximum strength and muscle size? Andrew Sheaff looks at some intriguing new research

Strength training has become an indispensable component of athletic training, being performed by athletes of all sports and ages. In most cases, the goal of strength training is strength, muscle hypertrophy (growth), or both. As the largest, strongest athletes are capable of lifting the largest weights, it has often been assumed that lifting large loads for small number of repetitions is the only effective way to successfully increase muscle strength and size. As a result, most training programs include this variation of strength training.

Lighter training loads

Despite the above, there is emerging research that lighter loads may be equally effective at promoting muscle hypertrophy in particular. Some studies have demonstrated that individuals can experience significant hypertrophy using light loads, comparable to those training with much heavier weights. However, similar improvements in muscle strength have not always been demonstrated.

It’s important to note that while improvements in muscle strength and hypertrophy are related, they are not always the same; the biggest athletes are not always the strongest and vice versa. Improvements in muscle strength and hypertrophy therefore are related but do not always respond similarly. So while low-load training does seem to improve muscle hypertrophy, its impact on muscle strength needs to be clarified.

It’s also not clear if using different loads during training has a unique effect on different muscle fiber types. It’s possible that lifting low versus high-loads may have a similar overall effective on muscle hypertrophy, but a very different effective on slow twitch versus fast twitch fibers. Fortunately, a recent study sought to provide some answers to these issues.

New research

A team of Scandinavian researchers sought to clarify how the responses to low-load and high-load strength training are both similar and different(1). They recruited 14 subjects with a strength training history of at least two years. All of these subjects were required to be performing strength training targeting lower body strength and muscle mass at least once per week. This helped to ensure that any potential findings would be relevant to strength training populations.

One of the problems with strength training studies is that many factors can influence strength and hypertrophy outcomes. For instance, appropriate nutrition is critical for hypotrophy response. The best strength training programs in the world won’t lead to measurable progress if a subject isn’t eating enough. The same could be said for numerous other influences. To avoid this issue therefore, the researchers performed what’s known as a ‘within-subjects’ design – each of the subjects served as their own comparison. As the researchers wanted to compare the impact of a high-load and a low-load training program, they had each subject perform a high-load training program on one leg and a low-load training program on the other. The side of the leg that performed each program was randomized. This made it much easier to account for any confounding factors that could influence the outcomes of the study.

What they did

The subjects performed two training session per week for eight weeks, with a one-week deload between the 4th and 5th week, where only one session was performed (to ensure some deeper recovery). The leg press and leg extension exercises were used as the training exercises during training sessions. During each training session, three sets were performed on both legs, with a 2-minute rest between sets. The subjects alternated legs by sets. The initial set was performed on alternating sides in each alternating week.

The key difference in the training programs was the weight used, and the number of repetitions performed:

- During the high-load training, subjects performed 3-5 repetitions per set, using a weight equivalent to 90-95% of their maximum.

- During low-load training, the subjects performed 20-25 repetitions per set, working with a weight that was between 40% and 60% of their maximum.

If the subjects performed repetitions outside the targeted range, the weight was adjusted up or down on subsequent sets. All sets were performed until the subjects were unable to properly complete another full repetition.

What they measured

Prior to training, the subjects underwent rigorous testing to determine muscle strength, muscle hypertrophy, and muscle fiber characteristics. The same testing protocol was performed after the training interventions as well. A maximum strength test was performed where the subjects progressively increased the weight they were lifting until they could no longer complete a single repetition. Testing was performed on both legs, and it was performed for the leg press and leg extension exercises.

To determine changes in muscle hypertrophy, ‘muscle thickness’ testing was performed using ultrasound. Ultrasound is an accurate and noninvasive method to image physical structures. The researchers were able to measure the distance between key anatomical landmarks that defined the muscle belly of the vastus lateralis (the large quadriceps muscle on the side of the thigh). Changes in the distance over time reflect changes in muscle size.

To determine muscle fiber characteristics, biopsies were performed before and after training on the vastus lateralis. These muscle samples were tested in several different ways. First, the researchers determined the percentage of muscle fibers that were type I, or slow twitch, and type II, or fast twitch. They then measured the average fiber size of each muscle fiber type. This was performed to help determine if the training protocols had a differential impact on the muscle fiber type adaptation.

The number of satellite cells and myonuclei were measured for each fiber type. Both satellite cells and myonuclei number have been linked to muscle hypertrophy outcomes. If changes in muscle hypertrophy were seen, the researchers wanted an explanation as to why. Again, it’s possible that the training protocols could have a different effect on fiber type, so these analyses were performed on both fiber types.

The findings

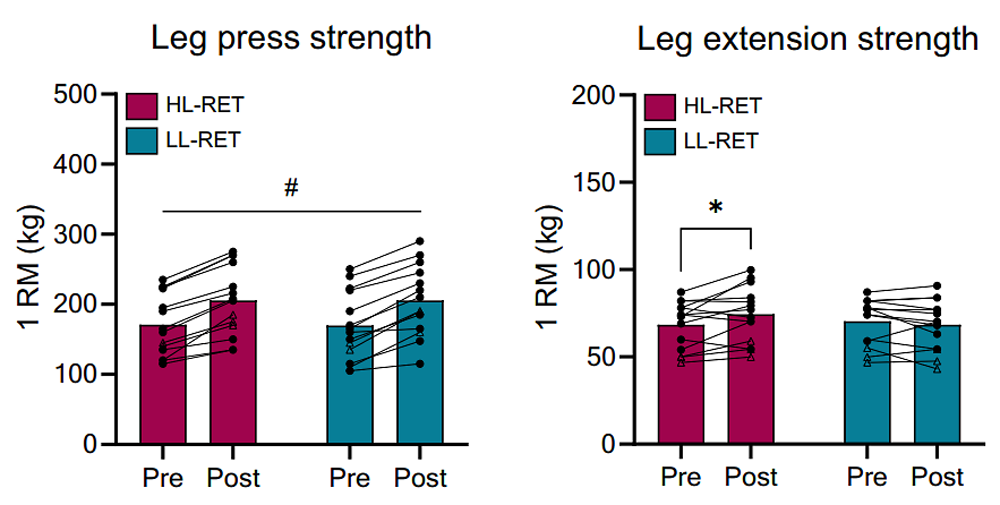

After the training and testing, the researchers had some interesting results on their hands. When comparing leg press exercise results, both training groups experienced significant increases in strength, with no differences between groups. The average improvement was 21% across both groups. By contrast, only the high-load training group was able to increase strength during the leg extension exercise (9%), with no improvement seen in the low-load group. It appears then that both high-load and low-load training can lead to strength improvements, although high-load training may be slightly more beneficial (see figure 1).

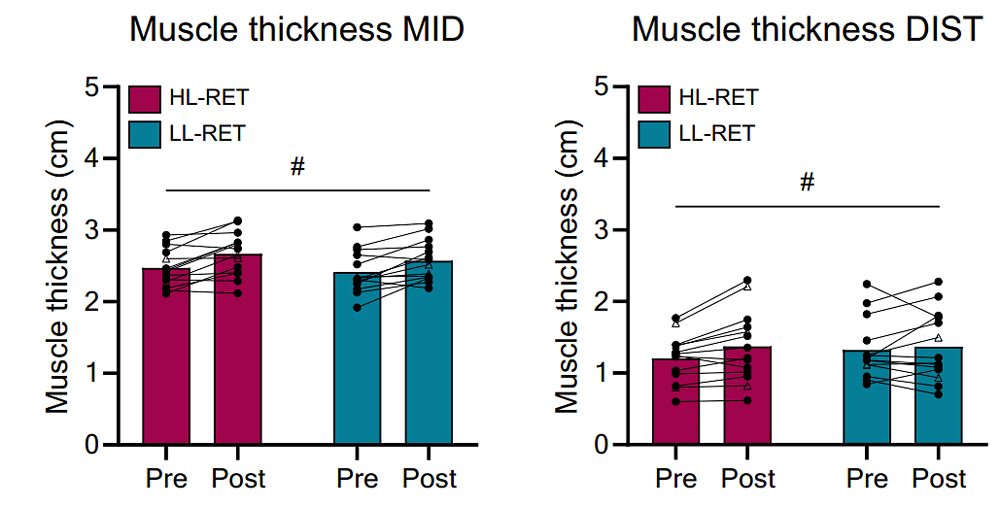

In terms of muscle thickness both groups demonstrated significant improvements at both the mid-thigh (7%) and towards the knee (8%). Importantly, there was no difference between the groups in terms of either absolute changes or relative changes (see figure 2). This finding demonstrates that regardless of the load, if individuals work towards failure during their sets, they can increase the size of their muscles.

Interestingly, no changes in muscle fiber size were seen during either training intervention. This was true of slow twitch, fast twitch, and mixed fiber types. Similarly, there was no change in myonuclei number. There was an increase in satellite cell activation in slow twitch fibers, but this change was present following both high-load and low-load training. These findings seem to indicate that the type of loading strategy has little to no impact on the adaptations seen at the cellular level.

Figure 1: Strength changes using low-load vs. high load training

Purple bars = high-load leg; turquoise bars = low-load leg. Solid circles = male participants; open triangles = female participants. For the leg press, both low- and high-load training resulted in significant and similar strength gains. In the leg extension however, only the high-load training seemed to elicit a significant improvement.

Figure 2: Muscle hypertrophy changes using low-load vs. high load training

Purple bars = high-load leg; turquoise bars = low-load leg. Solid circles = male participants; open triangles = female participants. Regardless of where muscle thickness was measured, the ‘pre to post’ gains were significant and similar - regardless of whether low- or high-load training was used.

Practical implications for athletes

When it comes to strength training, it appears that athletes and coaches have options. While high-load, low repetition training has traditionally been seen as the primary way to improve strength and hypertrophy, it now appears that much lighter loads can be equally effective at promoting these key outcomes. This is an important finding because high-load training is not always a feasible option. In some cases, it’s as simple as access. If sufficient strength training equipment is not available to perform high-load training, it’s obviously not possible to use high-load training. However, if lower loads are available, effective strength and hypertrophy outcomes can still be achieved. Similarly, high loads can sometimes be poorly tolerated by athletes. In the event of injury, athletes may be unable to use high loads as they create pain or worsen injury symptoms. However, they can often tolerate much lighter loads. By performing a sufficient number of repetitions, they may be able to maintain or even increase muscle strength and hypertrophy despite injury.

Another important consideration is variety. Training can become monotonous, and some athletes have a much lower tolerance for monotony. This research demonstrates that it’s possible to alter the training protocol without sacrificing important outcomes. As both high and low loads were found to be effective, it’s also likely that intermediate loads are effective as well, providing even more options. There is a caveat however; there were slightly better strength gains in the leg extension exercise following high-load training. While more research needs to be done, there may be a slight advantage to using high-load training when strength improvements are the primary objective. In that situation and if both options are available, it may therefore be wise to select high-load training protocols just to be sure. In summary then, when it comes to improving strength and muscle mass, there is more than one way to accomplish the goal. While you may not always be able to use both options, it’s valuable to be aware of them in the event they become necessary!

References

1. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2025 Sep 1;139(3):685-697. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00353.2025. Epub 2025 Aug 19.

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.