You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

HIIT or MIIT for maximum endurance?

Is a block of high-intensity interval training really the best option for lifting endurance performance, or can a similar block of moderate-intensity intervals achieve even more? SPB looks at brand new research

As all our regular subscribers will already know, interval training is an excellent method of improving fitness. Research shows that regular sessions of interval training can produce significant fitness gains in less time and with less effort than a higher volume of steady-state endurance training(1-4). Even better, the benefits of interval training can also be realised by amateur and recreational athletes – not just elite athletes. Indeed, recreational athletes who introduce intervals to a training schedule stand to gain even more than more advanced level athletes (who will almost certainly already be utilizing interval training in their training programs)(5).

Intervals: how hard?

When interval training first came to the fore as a training strategy, sessions were typically modelled around interval lengths lasting from 2-10 minutes, with intervals of 3-5 minutes becoming a popular and well-documented method for athletes and fitness enthusiasts seeking to improve aerobic fitness and endurance performance(6). The rationale for using 3-5 minute intervals is that there is a lag between starting a high-intensity effort and the cardiovascular system and muscles ‘catching up’ - a phenomenon that arises from the way the body responds to increase oxygen demand (more technically known as ‘oxygen kinetics’).

However, a landmark 1997 study by a Japanese professor called Izumi Tabata showed that just 8 x repeats of very high-intensity, shorter intervals of 20 seconds’ duration could achieve excellent gains in endurance fitness(7). In the years following, subsequent research on a wide range of athletes has indeed confirmed that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) using short intervals can be a very effective method of sharpening endurance fitness in athletes(8-10), which to a large extent explains the huge growth in the popularity in these short but intense interval sessions.

Duration matters too

The option of performing very short, very intense intervals instead of longer-duration intervals at a lesser intensity was something of a revelation for athletes short of time or an inherent love for interval sessions! However, the intensity of interval session isn’t the sole determinant of the fitness benefits that accrue. It turns out that what you get out of intervals depends on both the intensity and the total time spent working, not just one or the other(11). This explains why endurance athletes such as cyclists often mix in longer-duration more moderate-intensity intervals (MIIT) into their training programs(12,13). Indeed, research shows that these longer MIIT (although still challenging) sessions performed for four weeks or more can match the benefits gained from in terms of improving lactate threshold (the intensity at which fatiguing lactate begins to accumulate in muscles) and maximum power outputs when working near to maximum oxygen uptake (power output at VO2max)(14).

Because HIIT is a very effective and time-efficient method of training, there’s been very little recent research into the use of moderate-intensity interval training in athletes. Earlier this year however, the reported on new research on cyclists, which compared a 1-week block of MIIT and an equivalent 1-week block of their regular training in the build-up phase to a race season(15). In this study, researchers recruited 30 well-trained cyclists and compared:

· An MIIT block involving six moderate-intensity interval sessions over seven days, each with five to seven repeats of 10-14 minute work intervals (ie long intervals), performed at a perceived exertion (RPE) of 14-15 on the Borg 6-20 scale (‘somewhat hard’ to ‘hard’).

· A time-matched regular training block, during which the cyclists performed their regular preparatory-phase training routine, which primarily involved low-intensity exercise. However, they were also specifically instructed to perform either two MIIT sessions (as described above) per week, or one MIIT session and one high-intensity interval session per week.

The rather surprising finding was that the six moderate-intensity interval sessions performed over seven days, followed by a six-day active recovery period produced superior improvements in endurance performance compared to the same volume/time spent performing a regular training period.

HIIT vs. MIIT

Dozens of studies have compared a block (from one to several weeks) of HIIT to an equivalent-duration block of continuous steady-state training and found that HIIT sessions are superior for raising maximum aerobic capacity – especially in already well-trained athletes. In a similar vein, there have been (albeit fewer) studies comparing a block of MIIT to an equivalent block of continuous steady-state training; in these studies, the MIIT seems to excel for raising lactate thresholds, allowing athletes to maintain a higher power output before hitting their threshold. What there’s not been to date however, is a study directly comparing a block of HIIT to an equivalent block of MIIT in well-trained endurance athletes. However, published just three weeks ago, a new study by a team of Norwegian scientists has investigated this very question.

New research

Published in the ‘European Journal of Sport Science, this study compared the endurance benefits of a 1-week MIIT block to a 1-week HIIT block in well-trained cyclists(16). A secondary goal was to investigate the relationship between time spent to or over90% of VO2max and the training adaptations that resulted. The researchers hypothesized that the MIIT block would induce more favorable adaptations in lactate threshold measurements, while the HIIT block would induce more favorable adaptations in measurements related to VO2max. They also hypothesized that both blocks would similarly improve certain measures of endurance performance, such as maximum sustained power over 15 minutes.

What they did

In this study, 22 well-trained cyclists (21 males, 1 female) were recruited. The participants had an average VO2max of 69.5mls/kg/min, equating to high levels of aerobic fitness. These values of VO2max are typically seen in competitive road or track cyclists performing at a high level, and in this study, all the cyclists had been training for over four years, and were categorized as performance levels 3, 4 and 5 (which equates to ‘trained’, ‘well-trained’, and ‘professional’ respectively)(17). All of the cyclists had a history of consistent training, averaging more than five hours per week of training.

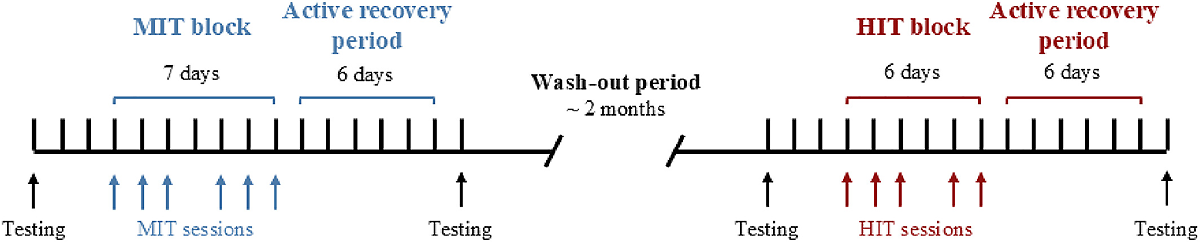

Following base line fitness testing, all of the cyclists had to perform two separate 2-week blocks of training in a randomized order (see figure 1). Each block comprised one week of intense training followed by a further six days of active recovery (light rides to promote adaptation without overload) and fitness testing on the 7th day. The two separate training blocks were as follows:

· MIIT block – consisting of six sessions over seven days. Each session involved 5–7 intervals of 10–14 minutes each at a rate of perceived exertion (RPE) of about 14.5 on the Borg 6–20 scale. This equates to a ‘hard‘ effort corresponding to roughly 75–85% of the cyclists’ maximal heart rate or power at lactate threshold, and emphasizing sustained efforts to build aerobic endurance.

· HIIT block – consisting of five sessions over six days. Each session involved 5 × 8.75-minute blocks, which were subdivided into multiple short but intense intervals (eg 30 seconds hard/15 seconds easy). The RPE was classed as ‘very hard’ with the intensity set at 118% of each cyclist’s 40-minute maximal sustainable power output. These intervals required supra-maximal efforts to maximize oxygen demand and anaerobic capacity, but with shorter total work time per session.

It’s important to note that the order of the blocks was randomized and the two blocks were separated by around nine weeks to allow full a recovery, and ensure the second block was free from the influence of the first (a so-called washout period). The ‘crossover’ design required that each cyclist completed both training blocks, thus eliminating variation due to individual differences in genetics and baseline fitness (each cyclist served as his or her own control for the other condition).

Figure 1: MIIT vs. HIIT study protocol

What they tested

As mentioned above, physiological and performance testing took place before and after each block. Note that these tests were carried out seven days after the end of each block to allow full recovery and maximum performance. This is similar to the taper period that endurance athletes schedule (or should schedule!) before a race or competition. The testing consisted of the following:

· A 15-minute maximal cycling time trial (PO15min) to measure sustained power output, which is a key metric for race-specific endurance.

· A 10-second maximal sprint (PO10sec) to assess anaerobic power.

· An incremental ramp test to determine each cyclist’s power output at a blood lactate of 4mmol/L (PO4mmol). This basically indicates the point at which blood lactate begins to rapidly accumulate, and marks the border between sustainable and unsustainable intensity.

· The maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) during the incremental ramp test (measured via gas analysis).

· Gross efficiency calculations from steady-state rides, which informed the researchers how efficiently the cyclists were utilizing oxygen to produce power on the bike. This is more commonly known as ‘cycling economy’ – see this article.

When all the data from collected, the researchers compared the pre/post results for each rider after each of the two blocks and used statistical analyses to tease out any key differences.

What they found

The findings showed that both the MIIT and the HIIT training blocks produced performance gains in the cyclists, albeit with slightly differing outcomes:

· Both the MIIT and HIIT block improved 15-minute sustained power (PO15min) by 4.9% and 2.8%, respectively. Although the MIIT gains appeared larger, a statistical analysis showed that due to the variability in the results, this difference wasn’t great enough to be statistically significant (ie it likely could have occurred through chance).

· When it came to sustained power at PO4mmol (lactate threshold), the MIIT block produced a greater improvement (4.5% gains) than did the HIIT (2.1% gains), showing its superiority for threshold riding.

· For sprinting power (PO10sec), the tables seemed to be turned; here the HIIT block produced a gain of around 1.5% whereas following the MIIT block resulted in an apparent decline of 1.5%. However, a further analysis showed that the difference in PO10sec between the HIIT and MIIT was just not quite large enough to meet statistical significance, although there was a definite trend towards favoring the HIIT. It is likely that if the study were to be repeated with a larger number of cyclists, the difference favouring HIIT for sprint power would have been ‘significant’.

· When it came to cycling efficiency (economy), there were no differences between the blocks; both trended towards slight improvements but the magnitude of this trend was similar in both blocks.

· For VO2max gains, both MIIT and HIIT produced small but non-significant increases of around 1-2% - ie there was no difference between the blocks. This is most likely because in very well-trained cyclists, VO2max already tends to be at or near its peak.

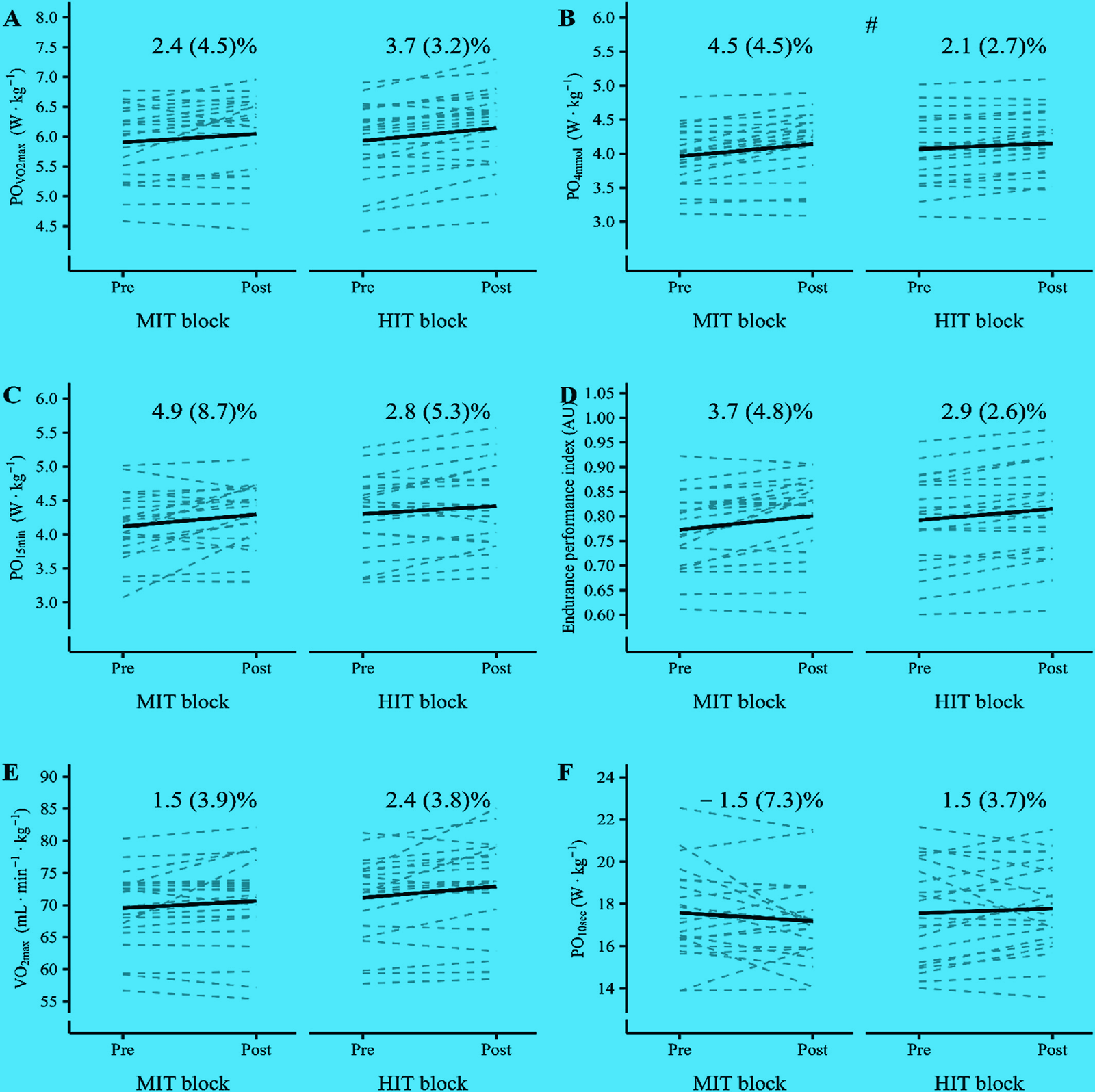

Figure 2 summarizes these findings in graphical form. When summing up, the researchers concluded that “Both a MIIT block (lower work interval intensity but longer work duration) and an HIIT block (higher work interval intensity but shorter work duration) can improve endurance performance determinants and PO15min with some work intensity-specific adaptations.”

Figure 2: Summary of key findings in MIIT vs. HIIT study

Individual data points (dotted lines) and average values (solid lines) for (A) maximal 1-min incremental power output during the maximal oxygen uptake (V̇O2max) test (POV̇O2max), (B) power output at 4 mmol•L−1 lactate concentration (PO4mmol), (C) maximal mean power output during the 15 min cycling trial (PO15min), (D) the endurance performance index, (E) V̇O2max, and (F) mean power output during the 10-sec all-out sprint (PO10sec), before (pre) and after (post) the moderate-intensity interval training (MIT) block and the high-intensity interval training (HIT) block. Although there were a number of trends, it was only B (PO4mmol) where there was a clear and significant difference between MIIT and HIIT.

Practical implications for athletes

These findings challenge the ‘high-intensity intervals are best’ narrative, which has gained a lot of traction in the media. In fact, the data from this study shows that both HIIT and MIIT blocks can boost performance, and the overall takeaway message from this study is that if you’re looking to sharpen up your endurance performance for a race or event, or simply trying to move off from a fitness plateau that you seem to have been stuck on for a while, a week-long block of either MIIT or HIIT can deliver results. In the findings above, either block type should be able to enhance riding performance in sustained efforts such as time trials or race breakaways, enabling around to 10–20 watts extra power over a 15-minute effort for the average rider.

That said, there are some differences between the two block types. When the cyclists performed MIIT blocks, the ability to ride sub-maximally but close to lactate threshold was improved to a greater extent than when performing HIIT blocks. In theory, this extra improvement should give cyclists an edge when needing to sustain relatively of high outputs for over an hour without straying over the threshold where fatigue begins to accumulate. In addition, MIIT improved ‘fractional utilization’ of aerobic capacity—a key limiter in endurance sports. In a nutshell, a greater proportion of the cyclists’ oxygen carrying capacity was available for energy at or near lactate threshold, conferring a potential performance advantage.

However, let’s not dismiss the HIIT block either. Although not quite as good at improving performance close to lactate threshold, the overall performance benefits were pretty much up to those of the MIIT block. And when it came to sprint performance, the HIIT block produced trend towards better 10-second outputs, potentially aiding hill sprints or final surges. Something else that should be noted is time investment; the gains seen in the HIIT block were achieved with a little over half the training time actually carrying out intervals, making it more time-efficient than MIIT. As a side note, it’s interesting to observe that although 22 cyclists started the study, a number dropped out (and were therefore excluded from the results). Of these, seven dropped out during the MIIT block and two during the HIIT block, anecdotally supporting the notion that HIIT sessions are psychologically easier to complete than long-duration intervals. Therefore, if time is tight or you have a natural aversion to interval sessions, you might find that a block of HIIT works better for you than a block of MIIT!

References

1. PLoS One. 2014 Apr 15;9(4):e95025

2. Eur J Sport Sci. 2016;16(3):344-9

3. J Sci Med Sport 2007; 10: 27–35

4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 294: R966–R974

5. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010; 20 Suppl 2: 1–106.

6. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Apr 2007;39(4):665-71

7. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997; Volume 29(3), pp 390-395

8. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010 Oct;110(3):597-606

9. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010 Sep;110(1):153-60

10. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014 Nov;114(11):2427-36

11. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2013. 23. 1: 74–83

12. Sports 2020. (8) 12: 167

13. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2007. (47) 2: 191–196

14. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2017. (49) 6: 1137–1146

15. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2025 (57) 8: 1780–1789

16. Eur J Sport Sci. 2025 Nov;25(11):e70067. doi: 10.1002/ejsc.70067

17. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2016. (11) 2: 204–213

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.