Strength for athletes: fixed vs. variable resistance

Can the benefits of strength training be enhanced by varying the resistance during a strength exercise? SPB looks at recent and brand new research

As we have highlighted in numerous previous articles, a large body of evidence shows beyond doubt that greater muscular strength is generally associated with superior performance across virtually every sport(1-4). Stronger muscles can develop more speed and power, are more resilient against injury and can produce force more efficiently (ie with less oxygen use) during sub-maximal endurance exercise. Strength training therefore is (or should be) a vital component of every athlete’s training program!

Routes to strength

In order to build, improve or maintain strength, muscular overload is necessary in any strength and conditioning protocol. To do this requires the application of external resistance or loading, and there are many ways to achieve this – eg free weights, machine weights, hydraulic or inertial systems, elastic bands and springs, bodyweight exercise etc. Regardless of the actual method used to apply resistance, that applied resistance can be categorized as follows:

· Isotonic – muscles work against constant weight/loading (eg lifting free weights or using machine weights).

· Isometric – muscles work at a constant (fixed) position regardless of load (eg core strengthening exercises such as holding a static plank position).

· Isokinetic – muscles work at a constant velocity regardless of load. No matter how hard you exert force, the speed of movement of the muscle being used remains the same.

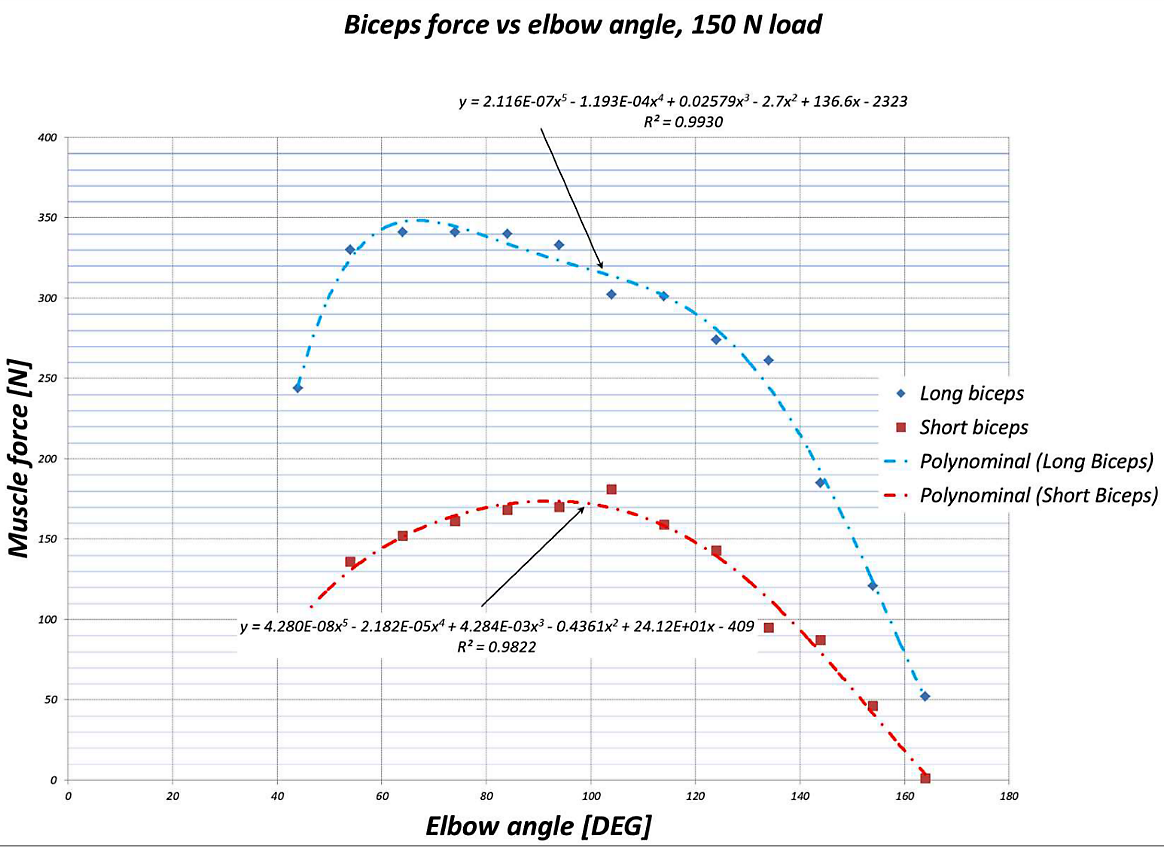

In most strength and conditioning settings, isotonic loading is employed thanks to the ubiquitous use of free and machine weights, which are conveniently adjusted and relatively inexpensive. However, in theory at least, isokinetic (sometimes called ‘isovelocity’) training devices offer some distinct advantages. In particular, isokinetic training allows maximum tension and loading to be applied to a muscle at all points through its range of motion; this is in contrast to conventional resistance (isotonic training), where the loading has to be chosen for a particular range of motion, meaning that at other points in the movement, the loading is less than optimal. An example of this is biceps curls, where, due to the physics of levers and muscle architecture, the muscles can exert high levels of force in the 60-120 degree range, but far less above and below this movement range (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Elbow angle and muscle force during biceps curls*

Variable resistance machines

Isokinetic machines are undoubtedly effective, and can be very useful in rehab settings. However, their main drawback is that such machines tend to be very costly and more complicated to operate, meaning that they are seldom used, even in advanced commercial gyms. The good news is that well designed resistance machines can be designed to generate more even and higher levels of tension and loading at all points through a muscle’s range of range motion via the incorporation of a cam design. A cam in this context is an irregularly-shaped wheel that changes the resistance/loading throughout the range of motion by altering the ‘moment arm length’, which matches the varying strength of muscles at different joint angles.

This design ensures that resistance is higher at the point in the movement when the user’s muscle is strongest (typically around the mid-range of motion – see figure 1) and lower when the muscle is weakest (at the extremes of the movement). When training on such variable resistance machines, users typically report that the tension feels much smoother and more continuous, without the typical ‘sticking point’ at a certain point in the exercise that is experienced on conventional machines. This biomechanical approach using cams is actually not new; indeed, it was pioneered by the brilliant and eccentric Arthur Jones, who developed his Nautilus resistance training machines way back in the 1970s, naming them after the logarithmic spiral of the nautilus shell due to the cam’s shape in these machines – see figure 2 and this article. It’s also worth mentioning that variable resistance can also be generated in certain free weight exercises – for example, by adding barbell chains in barbell squat or barbell bench press, which add resistance as you push up into the ‘stronger range’ of your muscle movement, and decrease resistance as you lower down (because more of the chain is resting on the floor – see this article).

Figure 2: The cam in the Nautilus ‘double-chest’ machine

Theory vs. practice

As regular readers will know, a theory about a superior training method is one thing. However, delivering actual performance benefits is another! Does training using variable resistance produce better results than using free weights and conventional fixed resistance/loading devices? A 2022 study looked into this topic. Published in the ‘International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health’ this study took the form of a systematic review and meta-analysis (where all the previous data on a topic is gathered together pooled and reanalyzed for more robust levels of evidence(5). In particular, the researchers examined whether variable-resistance training (VRT) was more effective than constant-resistance training (CRT) for improving maximum strength – defined as the greatest force a muscle can produce in one effort, often measured as one-repetition maximum (1RM).

The researchers searched databases for all studies comparing variable vs. fixed resistance training carried out up to January 2022 and included 14 controlled trials with a total of 414 participants, mostly young adults aged 18–30. Participants were a mix of trained (with prior resistance experience) or untrained. The training analyzed involved exercises like squats, bench presses, and deadlifts, and the programs used typically employed 1–3 sessions per week. The variable resistance exercises were mainly comprised of chain and elastic resistance combined with conventional barbell lifts. In terms of the training period, ten studies were under 10 weeks duration while four lasted longer than 10 weeks. The loadings used were quite variable – from 30 to 95% of 1-rep max (1RM). The proportion of the variable load component accounted for 10–35% of the total loading.

What they found

Results were analyzed using a statistical technique known as ‘effect sizes’ (ES), where a positive value indicates greater improvement. The key finding was the change in 1RM strength; overall, VRT led to significantly greater strength gains than CRT (effect size of 0.80, translating into a moderate to large benefit). This was true for both the trained and untrained participants, but the optimal loading differed according to training status. For trained individuals, VRT was superior when using heavy loads of at least 80% of 1RM (effect size 0.76). At lighter loads below 80% of 1RM, there was no benefit from using variable resistance over and above that produced by constant resistance. However, for those new to training, variable resistance produced bigger gains with lighter loads – ie below 80% of 1RM (effect size 2.38, a very large benefit). The researchers’ explanation for these findings was that in trained individuals, there’s a benefit from heavy VRT because it overcomes sticking points yet provides progressive overload in stronger positions. Untrained individuals however may gain more from lighter VRT via superior neural adaptations (eg better motor unit recruitment and coordination), whereas heavy loading may interfere with correct muscle recruitment and impair this process.

Brand new research

The study above clearly identified that using variable resistance in order to match muscle loading with muscle capability through the range of motion produces superior strength gains in both trained athletes and novices (providing the loading was 80+% 1RM for trained and under 80% 1RM for untrained). However, what would be good to know is if variable resistance training can enhance more than just maximal strength, and that is exactly what a brand new study by a team of Chinese scientists has investigated. Published in the ‘Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research’, this study has sought to build on the current knowledge by including more recent trials, and expanding outcomes beyond just 1RM strength to include velocity, power, and jumping ability. It also looked at the type of variable resistance used (ie chains vs. elastic bands) and the proportions of added variable loading added. Another goal was to separate the short- and long-term effects, to see if VRT benefits persist over longer periods of time.

Taking the form of a meta-analysis study (as the previous study above), the researchers compared variable resistance training (VRT)—using elastic bands or chains—with free weight training (FWT), which uses constant loads. As well as examining training effects on maximal strength (measured as 1RM), movement velocities, power output, and jump distance (vertical or horizontal), the study sought to establish both long-term training adaptations and acute (single-session) responses. To do this, studies were pair matched for long-term effects and acute effects, and also grouped by the proportion of variable resistance load (VRLP) added using chains or elastic bands: more than 20% of total loading or less than 20% of total loading.

Findings

The results showed that once again, variable resistance training produced greater improvements than fixed loadings – not just in maximal strength but in jump distance and height also. The best longer-term training benefits were seen with the use of chains rather than bands, and where the additional loading provided by the chains was around 20-37% of the total load. However, when the additional loading provided by bands or chains rose above 37% of total loading, gains in movement speed and power output (rate of force generation) were not as great as when fixed resistance (ie just free weights alone) was used. Overall, the authors concluded that for gains over the longer term, using variable resistances in the form of extra loading from (especially) chains or bands outperforms the use of fixed loading (ie using free weights along), especially when chains are used and the additional loading provided by the chains is in the region of 20-37% of the total load used.

Implications for athletes

What conclusions can we draw from these findings and how can athletes apply them in training? Firstly, the evidence is strongly in favor of using variable resistance when strength training. This variability can be added either by using strength machines with ‘cammed’ resistance loading, or by the use of chains and resistance bands when performing certain free weight exercises such as barbell squats, deadlifts and bench presses. When using machines with cams, simply choosing the appropriate weight that allows you to target your 6-8 reps is all that you need to do.

If you are using barbells chains or resistance bands, selecting the chain weight/resistance so that it comprises around 20-35% of the total loading will likely get you the best results. If you have the option, choose and use chains over bands. Beginners and novices who are experimenting with variable resistance should choose somewhat lighter loadings (of less than 80% of your 1RM). If you are a seasoned strength trainer, you should be using over 80% of 1RM as your loading target. While variable resistance is the preferred option for building strength overall, athletes who are training primarily for speed and power need to be cautious and not add too much additional variable resistance and it may compromise their training goals.

References

1. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Dec;52(24):1557-15

2. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021 Mar 17;6(1):29

3. J Sports Sci Med. 2025 Jun 1;24(2):406-452

4. Eur. J. Sport Sci 2018. 18, 1199–1207

5. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jul 13;19(14):8559

6. J Strength Cond Res. 2025 Dec 30. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000005369. Online ahead of print

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.