You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength training: grip width matters for shoulders

The shoulder press is king of shoulder strengthening exercises. But what is the optimum grip width to ensure the best results while minimizing injury risk? SPB looks at new research

If you’re serious about performance, you probably already engage in regular strength training, and with good reason; a very large body of evidence has now accumulated that strength training not only helps develop strength and power, but can also reduce the risk of injury and improve endurance performance by making muscles more efficient(1-5). But while much research has been carried out on the benefits of strength training, there’s less data on how to optimally execute strength training exercise to deliver the best results. In this article, we will take a look at how changing your hand spacing on a barbell or shoulder press machine while performing overhead presses alters the forces on your body, and the implications for those seeking to build shoulder strength without risking injury.

Shoulder strength matters

Most athletes who strength train for performance understand that the leg muscles – because they’re involved heavily in most sporting activities – need to be trained as part of strength a workout. But why does shoulder strength matter? It turns out that the shoulder joint is the critical link that transfers power from the legs/core to arms and hands, and is therefore incredibly important in any activities involving the arms – eg tennis serving, swimming, throwing, catching, batting, and in many manual tasks such as digging, sawing, chopping, painting, plastering etc.

When the shoulder joint (more technically known as the glenohumeral joint) is strong, it can better withstand any forces transferred through it. The stabilising muscles of the shoulder joint (rotator cuff) are also required to provide the eccentric braking force needed to decelerate the arm safely – for example when catching, blocking a punch etc – which demands enormous cuff strength(6). It’s also known that strong and powerful shoulders can increase power during throwing or impacts by reducing energy loss during the transfer of force(7). Strong shoulders also confer injury prevention benefits. The incredible mobility of the shoulder joint comes at a price, which is that sufficient muscular strength must be present to protect overuse damage. Therefore, if shoulder strength is sub-optimal, injury is much more likely, the data on this being clear and unequivocal. For example:

- Baseball pitchers with preseason external-rotation strength deficits ≥10 % are 2.4–3.5× more likely to suffer arm injury(8).

- Increasing rotator-cuff and scapular-stabilizer muscle strength by 15-20% can reduce a swimmer’s shoulder pain incidence by 40–60 % in any given season(9).

- Pre-season shoulder-strength screening predicts 60–70 % of subsequent overuse injuries in elite handball and volleyball athletes during that season(10).

Strong shoulders are also important for endurance athletes such as rowers, swimmers and triathletes.

Research shows that fatigue-resistant shoulders can maintain proper biomechanical movement patterns for longer, thereby increasing efficiency. For example, swimmers with higher shoulder muscle strength/endurance have been shown to swim around 1–2 % faster over 200 metres than those with lower shoulder strength(11).

Shoulder press exercises and grip width

The shoulder press exercise, whether performed using a barbell, dumbbells or a shoulder press machine is undoubtedly the ‘king’ of shoulder strength exercises. But here’s a question for you: when you grab a barbell or the handles of a shoulder press machine to perform overhead presses, what grip width do you use? Do you simply go for shoulder-width grip, or go wider? Or maybe you go narrower? More importantly, how do you know which width is best. It turns out that even experienced strength training debate this question endlessly, with some arguing that a wider grip loads the shoulders more fully, while others disputing this, and counter arguing that a wide grip offers no extra benefits but does increase the risk of shoulder injury.

Shoulder press grip width actually matters a lot because it affects the forces the shoulder muscle experience and the muscle activation patterns. This means that the training stimulus delivered to the shoulder muscles can be impacted by grip width, and also means that an incorrect grip width could result in excessive force experienced by some of the shoulder muscles, leading to muscle niggles or even injuries. There’s been quite a lot of research into the effects of grip width when performing the bench press exercise, but for overhead presses, there actually very little data. Fortunately, exercise scientists from the University of Sydney and co-collaborators in the US, have managed to provide some evidence-based answers to the ‘optimum grip width’ question(12).

New research

In this study, which was published earlier this month in the journal ‘Sports Biomechanics’, scientists investigated the impact of grip width on the movement patterns and the forces involved in producing those patterns when performing the seated barbell shoulder. To do this, the researchers recruited 11 males (average age 26 years, average height 180.4 cm and average body mass of 87.0 kg). All the participants had at least two years’ of regular resistance training experience, which included regular shoulder press exercises. All were also healthy and had suffered no recent upper-body injuries. These selection criteria were chosen to ensure all participants had the experience to perform the exercise correctly under the varying conditions of the trial.

What they did

All the participants completed three separate shoulder press sessions on three different occasions, with each session dedicated to using one particular grip width during the exercise testing. These were as follows:

· Narrow grip width - 1.0 times biacromial width (roughly shoulder width)

· Medium grip width - 1.5 times biacromial width

· Wide grip width - 2.0 times biacromial width

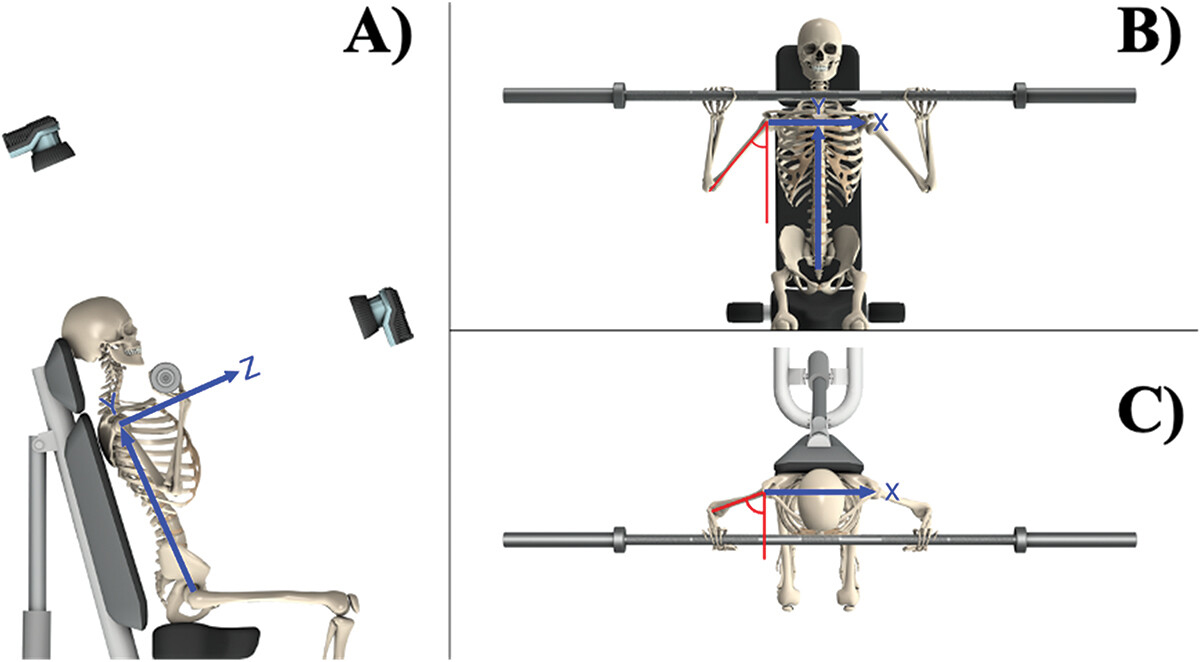

Importantly, the biacromial width factors used (1.0x, 1.5x and 2.0x) were tailored to each participant’s individual anatomy – ie multiples of the distance across the shoulders measured at the acromion bones for that participant. This can be seen in figure 1B & 1C as the distance given by ‘X’.

Figure 1: Biacromial width and movement angles measured during shoulder pressing

In each session, all the participants had their loading individually adjusted to that they could perform eight repetitions to volitional failure – ie they were unable to complete a ninth rep with strict and proper form. This was initially set for the medium grip width and was adjusted slightly where necessary for the narrow and wide grip widths. As shown in figure 1, the exercise was performed while seated on a standard bench with back support, feet flat on the floor, and a barbell starting at collarbone height. The concentric phase (the upward pressing motion during which muscle fibers shorten) was the primary focus of the researchers; as in all resistance exercises, the concentric phase is more demanding than the lowering (eccentric) phase and is therefore the phase in which movement deviations are first seen.

Recording the data

To capture the movement patterns, a 3D motion capture system with 12 infrared cameras tracking 22 reflective markers on the participants’ bodies and on the barbell was used. Force plates under the bench measured the forces transmitted through the participant’s bodies to the ground. Meanwhile, custom software calculated joint angles, barbell trajectories, and internal loads like net joint moments (NJMs)—which represent the torque or rotational force at the shoulder and elbow joints.

An analysis technique known as statistical parametric mapping (SPM) was then employed to calculate grip width effects at every point in the lift, from start to finish. The beauty of SPM is that it can examine force and movement differences across the entire exercise rather than just record peak values. In particular, the researchers focused on the movement patterns of the penultimate rep (ie the rep before the final failure rep); this is because this was the last rep of the set to be performed correctly, but the accumulated fatigue at this point tended to amplify biomechanical differences.

What they found

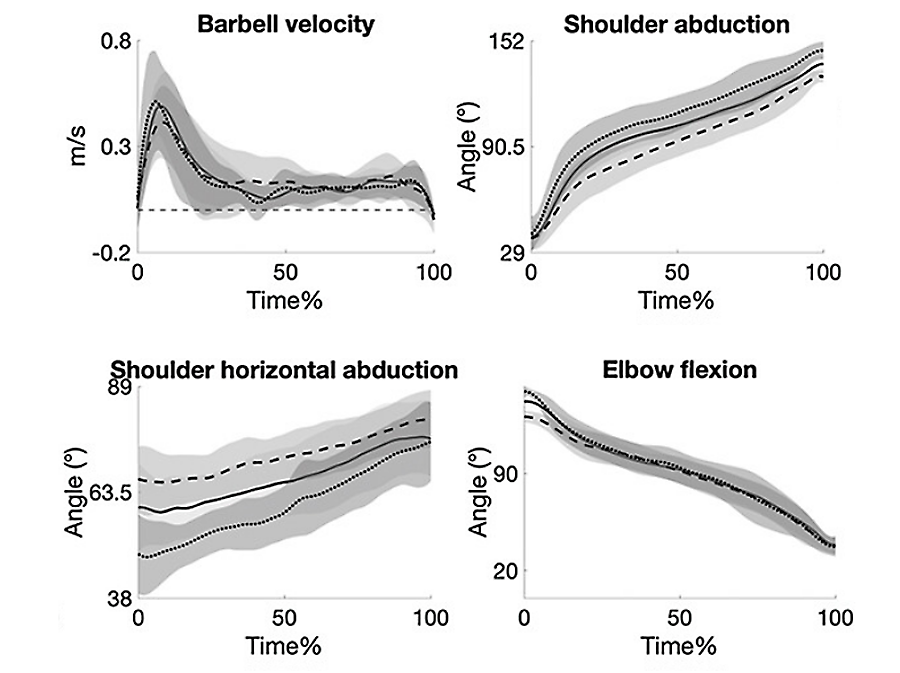

There were a number of findings that emerged relating to the different grip widths, but first and foremost was that grip width most definitely does significantly impact both shoulder press performance and biomechanics – not just in one phase of the lift, but through 100% of the range of motion (see figure 2). The main findings were as follows:

· The narrow and medium grip widths enabled lifting heavier absolute loads (about 5-7% more than wide grip) – most likely because these widths align better with the deltoid muscles’ ‘line of pull’, reducing leverage disadvantages.

· The wide grip width reduced lifting capacity, which was because of the increased shoulder abduction demand (mechanically disadvantageous).

· The narrower grips produced greater ranges of motion at both the shoulder (the upper arm was able move upwards by around 10% more) and elbow (arms were able to straighten by around an extra 8% more). This meant arms move through a greater range of motion during the narrow/medium-width grip press, potentially engaging more muscle fibers, and also increasing the time under tension (a good thing).

· The wide grips moved the bar more laterally (outward), creating a slight arc away from the midline, while narrower grips kept it straighter and more medial (inward). As a result, the wide generated higher lateral forces (up to 15% greater peak force), demanding more stabilization from rotator cuff muscles.

· The wide grips reduced forces at the elbow by 12-15%, easing triceps loading, but increased shoulder loading by a similar amount due to greater abduction angles. When the narrow grip was used, this loading pattern was reversed.

Figure 2: Movement patterns during narrow, medium and wide grips

Barbell velocity (in m/s), shoulder abduction angle, shoulder horizontal abduction angle and elbow flexion angles from 0 to 100% of the shoulder press lift. Dotted lines = narrow width grip; solid lines = medium width grip; dashed lines = wide grip width. Note how these all differ across the whole range of motion of the lift.

Practical implications for athletes

If you regularly perform shoulder press exercise in your strength routine, what do these findings mean for you? The first thing to say is that there no ‘one size fits all’ grip; the grip width you use should be influenced by your own anatomy, training goals and any injury issues or history you may have. If developing maximum strength and power is your goal, using a higher load with a medium or narrow grip width will involve more muscle fibres in the shoulder (and in the triceps on the rear upper arm). However, the increased loading of the elbow joint with a narrower grip width could be an issue for those with pre-existing elbow injuries such as lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow).

To shift the emphasis away from the triceps and elbow, and to isolate the deltoid muscles more, a wider grip is recommended. The downside of this grip width is that the added lateral forces increase shoulder abduction, which might exacerbate shoulder impingement risks in individuals, or aggravate problems in those with a history of rotator cuff injury. A wide grip width may also be a problem for those with poor scapular control. Where these injuries are or have been a problem, a medium grip (1.5x acromion width) probably strikes the best balance overall; this grip width can minimize overloading forces while maintaining a strong training stimulus and good range of motion.

These width recommendations hold true whether you use a barbell or shoulder press machine to perform overhead presses. However, if you use barbell training, it’s important to monitor the bar movement and avoid excessive lateral and forward/backwards deviations (which can cause additional shear forces in your shoulder tissues over time) regardless of grip width you use. Another option of course is to use dumbbells; where each shoulder works independently. There’s no grip width choice of course, but you can achieve the same kind of effects simply by altering the path of the dumbbells as you lift. Lifting to a more overhead position (imagine pushing towards the apex of a triangle above your head) will equate to a narrower grip width while lifting more vertically so the dumbbells remain vertically aligned with the left/right acromion points will produce more of a medium grip width effect.

References

1. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014. 24, 603–612

2. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform 2016. 11, 283–289

3. Sports Med 2018. Auckl. NZ 48, 1117–1149

4. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Dec;52(24):1557-15

5. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021 Mar 17;6(1):29

6. Sports Biomechanics 2018. 17(2): 260–274

7. ‘Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning’ (4th ed.) 2016. Human Kinetics

8. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2015. 3(10): 2325967115605072

9. Journal of Athletic Training 2016. 51(6): 456–463

10. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2017. 45(7): 1632–1639

11. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2009. 19(4): 478–486

12. Sports Biomechanics 2025. 1–14 doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2025.2590028

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

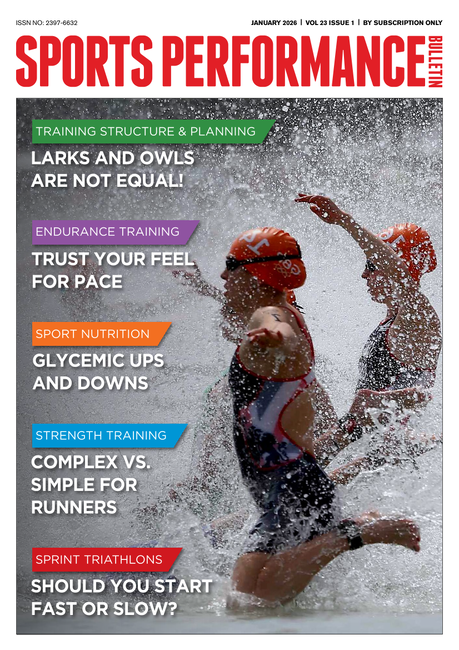

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.