Endurance training: sleep to win!

Just how important is sleep quality and quantity for long-term endurance performance? SPB looks at new research suggesting that it’s much more important than we previously imagined

The importance of enough good-quality sleep for mental performance has long been understood. In the last two decades or so however, researchers have concluded that sleep also has a huge role in regulating many physiological functions, which can directly affect performance(1). In short, even though there is still a widespread perception among the public (and many athletes too) that sleep quality and quantity don’t really matter that much, the fact is that they certainly do!

Understanding sleep deficiency effects

Research has identified that when you go short of restful, high-quality sleep, there are a number of potential performance consequences. Both total and partial sleep deprivation over a period of days have been shown to impair exercise performance; research has shown that a single night of sleep deprivation can decrease performance during an endurance running test on the following day(2-6). These same studies also suggest that maximal aerobic power may decline by up to 50% after partial sleep deprivation and that losing four hours of your normal sleep can significantly reduced both peak and mean power outputs during 30-seconds maximal sprints. All of the above are compounded by the fact that sleep deprivation, especially when chronic, can lead to a lack of motivation to train and reduced ability to think clearly!

Much of the research studies into sleep (deprivation) and performance have been laboratory based, where athletes started the trial fresh, underwent a period of sleep deprivation and then were assessed during a subsequent exercise test. However, most athletes train on a day to day basis, and fairly recent research also points to the fact that a bad night’s sleep during a run of training days affect can negatively impact an athlete’s ability to perform in those later training days.

Sleep loss during normal training

In a 2021 study, which SPB previously reported on, Korean scientists looked at the impact of sleep deprivation on the next day’s exercise performance after a day when vigorous training had taken place (ie more reflective of normal training routines)(7). Eleven athletes completed two identical exercise trials on two separate occasions:

· Day 1 – Ninety minutes of continuous running at 75% VO2max (moderate-hard intensity) followed by 100 drop jumps to induce high levels of muscle fatigue.

· Day 2 – Twenty minutes of sub-maximal running at 75% VO2max and then a time to exhaustion running test (TTE) at 85% of VO2max (hard to very hard).

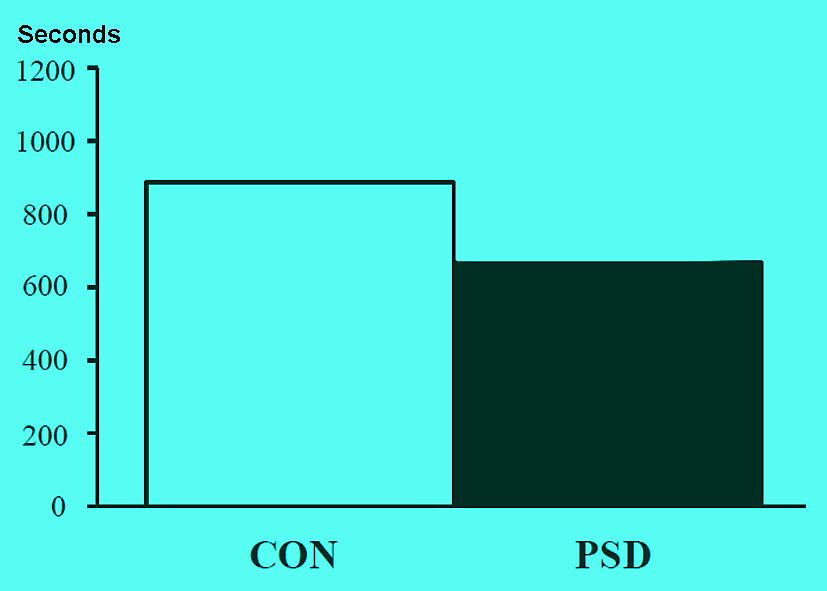

The only difference between the two trials was that in one trial (the control), the athletes were allowed to sleep for eight hours on the night of day #1, while in the other trial however, sleep duration was shortened to just 40% of normal (ie just under three and a quarter hours) between days 1 and 2. When comparing the normal sleep/sleep deprived performance results on day #2, the research discovered that there was a big impact on performance; the time to exhaustion at 85% VO2max was very significantly shorter in the sleep deprivation trial than in the full night’s sleep trial (665 seconds vs. 887 seconds – see figure 1). Also, when sleep deprived, the athletes were less able to draw on their muscle carbohydrate (glycogen) reserves - either because the sleep deprivation made it more difficult to do so, or because it had somehow negatively impacted their ability to synthesize muscle glycogen overnight following the food intake the evening before.

Figure 1: Time to exhaustion at 85% VO2max in full vs. deprived sleep

Swimmers, sleep and performance

Sleep deprivation and the performance penalties it brings can be a problem for any athlete at any time, but swimmers training in a squad setting may be more vulnerable than most. The constraints on pool availability means that early morning training sessions are commonplace for many club/collegiate swimmers - a factor that has been linked to poorer sleep habits among these athletes(8). Research investigating the sleeping behavior of elite swimmers has found that during nights preceding early morning training, swimmers obtained an average of 5.4 hours of sleep, whereas they obtained 7.1 hours of sleep on nights preceding rest days – clearly demonstrating that early-morning training sessions can significantly reduce the amount of sleep obtained by elite swimmers(9).

Frequent training without the optimum amount of sleep can be a real issue for swimmers as this is a factor known to be associated with an increased risk of developing ‘overtraining syndrome’(10). And even where swimmers do not become overtrained, chronic sleep deprivation combined with a rigorous training program can lead to training maladaptation, including reduced exercise capacity and a prolonged recovery time(11). In short, recovery is impaired and gains in fitness are reduced compared to the same training program executed with adequate sleep. A further factor to consider is sleep quality. Sleep quality is a measure not just of total sleep duration, but also the ‘sleep architecture’. This is a measure of the amount and distribution of two different kinds of sleep patterns: slow‐wave sleep (SWS) and rapid eye movement (REM sleep), which are both integral components of any recovery regimen (see box 1).

Box 1: Sleep architecture and athletic performance

Sleep duration can be simply categorized as being either ‘slow-wave sleep’ (SWS – also known as deep sleep or non-REM sleep) or Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep. SWS is a phase of sleep characterized by slow, high-amplitude delta brain waves with a frequency varying between 0.5 and 4Hz. During SWS, heart rate, breathing, and body temperature decrease, and the body enters a state of deep relaxation. SWS typically dominates the first half of the night, lasting 20–40 minutes per cycle, and is hardest to awaken from.

By contrast, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is a lighter kind of sleep where the brain activity increases dramatically, with fast irregular waves almost resembling wakefulness. As its name suggests, the eyes move rapidly under closed eyelids, and this is the phase were vivid dreaming occurs. REM cycles comprise about 20–25% of total sleep duration in adults, and tend to lengthen as morning approaches. SWS is the non-dreaming phase of sleep while REM is dream-heavy and mentally stimulating. Each sleep cycle contains both phases but as the night progresses SWS decreases and REM increases.

From an athletic perspective, SWS is crucial for physical restoration since this is the phase that triggers growth hormone release, promoting muscle growth, tissue regeneration, bone strengthening, and immune function(12). Without adequate SWS, physical recovery and body maintenance is impaired, leading to fatigue, weakened immunity and slower healing in injured athletes. REM sleep on the other hand is vital for cognitive restoration, aiding memory, learning, and emotional regulation(13). It also indirectly supports physical recovery by helping the brain to process stress and maintain key neural pathways involved with motor skills and coordination. In plain English, SWS stimulates repair and recovery of the body, while REM helps restore the mind-body connection. Disrupting either through shortened or disrupted sleep can impair athletic performance.

New research on swimmers and sleep

Given the sleep challenges that many swimmers face when performing early-morning training sessions, it’s perhaps surprising that there’s very little data on the longer-term impacts of sleep duration and quality in swimmers undergoing regular training. However, a new study on this topic by scientists at Pennsylvania State University and the University of Southern California makes for intriguing reading(14). Published in the ‘European Journal of Sports Science’, the goal of this study was to investigate the relationship between sleep quality, measures of training loads/responses and swimming performance in elite collegiate swimmers over a 6‐week period within the competitive season, during which training load and intensity were at its highest prior to post-season championship competition.

Twenty six swimmers (10 males, 16 females) were recruited for the study, all of whom were in good health, free of injury, and able to train without limitations. Data collection took place over a 6-week period and consisted of assessment of body composition (lean muscle mass/fat), training volume duration, distance covered during training sessions, and the training responses. These responses included the strain/load of each workout, average exercise heart rate, and maximal exercise heart rate, and energy expenditure - all obtained from a wearable device (WHOOP wearable devices , Boston, MA). Subjective measures of training intensity were captured via a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) on a scale of 0 to 10 using the Borg CR10 scale, which was obtained for each participant after each training session. Training measurements were collected together with sleep measurement – ie each day’s training data was matched to the previous night’s sleep data.

Sleep and performance measurements

Various measures of the swimmers’ sleep quantity and quality were also recorded by WHOOP devices (which have demonstrated good levels of validity and reliability against gold‐standard measurements of sleep used in the lab). The specific sleep variables of interest captured by the WHOOP included total sleep time (hours:minutes), sleep disturbances (number of disturbances accumulated over an entire sleep bout), sleep efficiency (defined as the % of time asleep while in bed), and amount of time (hours:minutes) and percentage of time spent in the waking state, light sleep, slow‐wave sleep (SWS), and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

As well as training metrics, the researchers wanted to get a handle on the relationship between sleep and actual performance. Therefore, a 200‐yard freestyle time trial was completed during the study’s data collection period as a measure of swimming performance. This time trial occurred during the team practice time, and followed the protocol commonly used in elite swimming participation. As a result, the time trial was overseen by members of the team’s coaching staff as well as certified lifeguards. Prior to the date of the time trial, participants were encouraged to treat the time trial as they would an actual competition and to prepare accordingly and swim flat out to achieve the very best time they could. Once all the data had been collected, the researchers performed a statistical analysis to determine whether and how sleep metrics were correlated to training and performance metrics.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

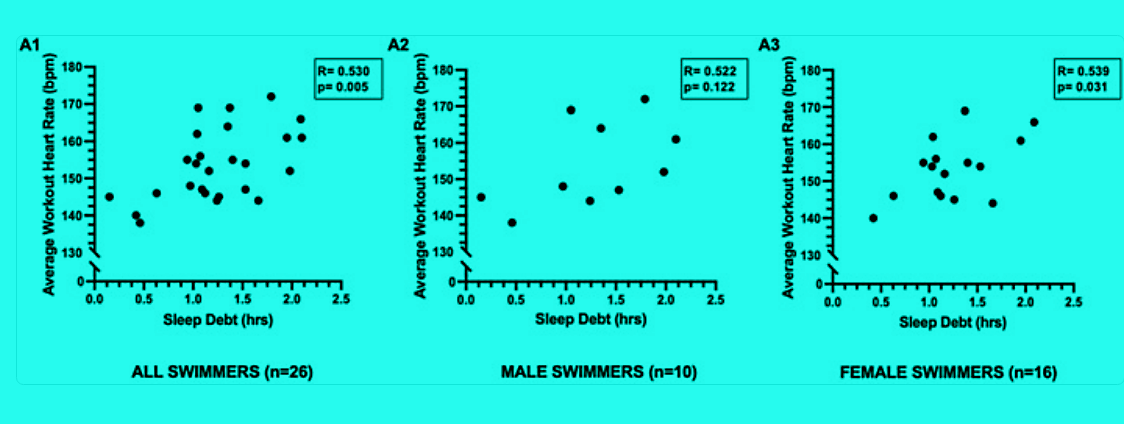

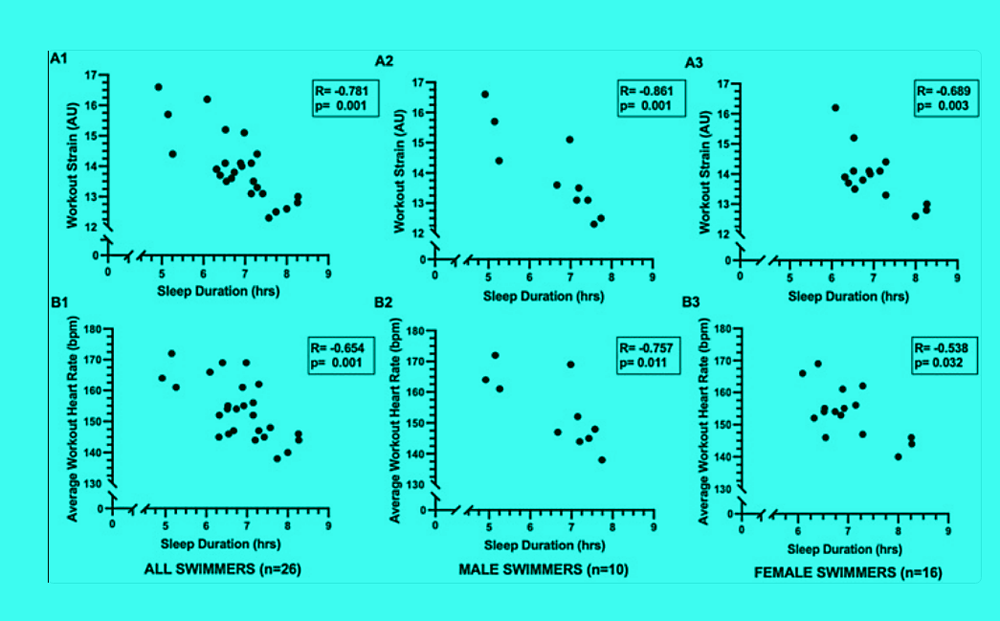

· In all swimmers, shorter sleep duration was related to increased cardiovascular strain for a given workout (figure 2).

· The more sleep debt (shortfall) the swimmers had accumulated during the previous nights, the higher the heart rate during exercise at a given intensity (figure 3).

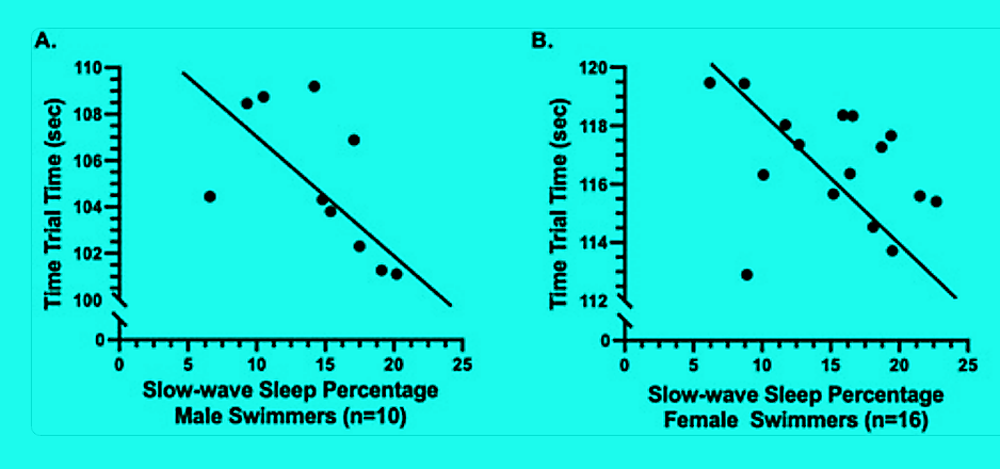

· The greater the sleep duration and the more slow wave sleep (SWS) the swimmers had had the previous night, the lower the heart rate during a given workout and (importantly) the faster they swam the 200-yard time trial (figure 4). These faster time trial times were very strongly correlated to SWS duration.

When summing up their findings, the researchers commented that “sleep quality was related to both training responses and swimming performance in all swimmers, whereby swimmers with higher sleep quality exhibited lower average workout strain and heart rates during training and faster swimming performance during the time trial swim.”

Figure 2 (top): Sleep duration/cardiovascular strain & Figure 3 (below): Sleep debt average workout heart rate

Figure 4: Time trial times and SWSe

Practical implications for endurance athletes

Most studies on sleep and athletic performance have looked at one or two night’s sleep loss/reduction and have been carried out in a lab setting rather than in athletes undergoing real training programs in the real world. This study is important because it shows that getting enough good quality makes a real difference to training and performance outcomes in the longer term. In particular, it shows that that getting enough sleep is not just about recovery – it translates into real-world performance gains via superior training adaptations. In that respect, improving sleep quality and quantity can be considered a performance-enhancing intervention on par with upping your training load!

One of the main take-home messages for athletes is that chronic under-sleeping is common. Even in these highly-motivated collegiate swimmers, 58% of athletes averaged less than seven hours sleep per night during periods of heavy training. Amateur athletes aren’t exempt from this risk either; recreational and amateur swimmers, triathletes, and runners who train early mornings or who hold down full-time jobs routinely report similar or worse sleep.

The negative impacts of sleep shortfall shouldn’t be underestimated; sleep quantity and quality directly affect training stress, with shorter sleep duration and lower proportions of slow-wave sleep In plain English, that same set of intervals or race-pace workout after a poor-sleep night will almost certainly significantly harder and more tiring, while producing less aerobic benefit. Over days and weeks, the negative impact of sleep shortfall adds up. In the study above, a single night of good sleep or a 3-day streak of high SWS% predicted the swimmers’ 200-yard freestyle times better than any training variable measured. Translated to running or cycling, this suggests that the difference between a personal best and an average day when performing a 25-mile cycling time trial, half-marathon, or Ironman may often come down to accumulated sleep debt rather than slight differences in taper or carbohydrate loading!

For endurance athletes, the overall message is clear: looking after your sleep needs is non-negotiable and should be considered an integral part of your training plan. In practice, this means that you should try wherever possible to smooth the pathway to better sleep and more of it. This means ensuring consistent bedtimes and evening wind-down routines, and maybe altering your schedule – for example, shifting your early-morning training sessions till later on, or if you can’t getting an afternoon nap/retiring to bed earlier. The good news is that the data from the above study shows a little extra sleep can go a long way; gaining even 30-60 minutes more sleep made a surprisingly positive difference. If you’re someone who struggles with sleep because you find it difficult to establish a good bedtime routine, or struggle to fall asleep after retiring, this article by James Marshall provides a number of invaluable tips and guidelines!

References

1. Nature 27 October 2005; 437:7063

2. Eur J Appl Physiol 2013;113:241-8

3. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1991;63:77-82

4. J Sports Sci 2001;19:89-97

5. Eur J Appl Physiol 2009;107:155-61

6. Eur J Appl Physiol 2003;89:359-66

7. Phys Act Nutr. 2021 Mar;25(1):1-6

8. International Journal of Exercise Science 2022. 15, no. 6: 423–433

9. Supplement, European Journal of Sport Science 2014. 14, no. S1: S310–S315

10. Frontiers in Physiology 2018. 9, no. 436: 436

11. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2019. 51, no. 12: 2516–2523

12. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2018. 41: 113–132

13. Sports Medicine 2015. 45, no. 2: 161–186

14. Eur J Sport Sci. 2025 Dec;25(12):e70090. doi: 10.1002/ejsc.70090

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.