Cycling and bone health: jump to it with collagen!

Despite being great for cardiovascular health, there are concerns that high-volume cycling training can harm bone density and skeletal health. With that in mind, SPB looks at new research on how cyclists can protect their bone health while maintaining their training loads

Assuming that cyclists undertake a properly structured training program, and that they allow adequate time for recovery with good nutrition, the health spin offs of increased cycling performance are almost always beneficial. Indeed, research shows that increasing aerobic fitness through activities such as cycling confers several health benefits:

- Better control of blood sugar(1).

- Reduced blood pressure(2,3).

- Lower levels of (unhealthy LDL) blood cholesterol(2,3).

- Reduced body fat(4).

- Reduced risk of cardiovascular heart disease (as the result of 1-4)(5,6).

- Better quality of life in older age(7).

Bone health drawbacks

However, one area where (unlike many other forms of exercise) cycling might not deliver health benefits is bone health, or more specifically, increasing bone mineral density (BMD). Building and maintaining good levels of BMD matters for health because low levels of BMD are associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a disease that affects mainly (but not exclusively) older people in which bones gradually become more fragile and likely to break. These broken bones are also known as fractures and typically occur typically in the hip, spine, and wrist.

Osteoporosis (which quite literally means ’porous bones’) is often known as the ‘silent crippler’ because it often progresses painlessly and unnoticed, until a bone actually breaks. Although any bone can be affected, fractures of the hip and spine are particularly problematical because they can produce a number of long-term complications including loss of ability to walk and permanent disability, loss of height and severe back pain.

Improving bone health

Although osteoporosis remains poorly understood as a disease process, we do know that being physically inactive is a very big risk factor for developing osteoporosis. This is because vigorous ‘bone-loading’ with physical activity is very effective at stimulating the uptake of calcium into bones, thereby helping to build bone mass in earlier years, and reducing the loss of bone mass in later years(8).

Research has shown that the higher the muscular and impact load (gravitational) forces, the higher the BMD produced; so for example, gymnasts whose sport requires high loadings and impacts tend to have higher BMDs than endurance runners(9). There’s also evidence that activities that develop strength (such as weight training) are particularly effective at producing high BMDs in the hip and spine(10,11). By contrast, those who participate in sports with plenty of muscular motion, but without substantial loading (eg swimming) do not achieve the high BMDs of sports with higher loadings(12).

Bone loading and BMD in cyclists

Muscular loading during cycling can be very high, especially during sprinting – for example on the track. On the other hand, the smooth spinning nature of the pedaling action and the fact that cyclists are supported by their saddle means there’s virtually no bone loading associated with gravitational impacts (unlike the shock of foot-strike during running or field sports). In distance road cycling therefore, where sprinting is only a minimal component, the degree of total bone loading is likely to be quite low. This fact has prompted researchers to look at the issue of BMD in cyclists more generally, and the past 14 years’ or so of research makes for uncomfortable reading.

A study on BMD using DXA (dual X-ray absorptiometry – the most accurate method of determining bone density and mass) by Brazilian scientists found that while well-trained young cyclists were aerobically fitter and had more muscle mass, their bone BMDs were no higher than sedentary controls of the same age(13). However (and more worryingly), some studies indicate that road cycling could actually have a detrimental effect on BMD. For example, French research found that compared to healthy non-cycling males, road cyclists had lower levels of BMD, and this was despite the fact that they were consuming significantly more dietary calcium (considered essential for bone health) than their sedentary counterparts(14).

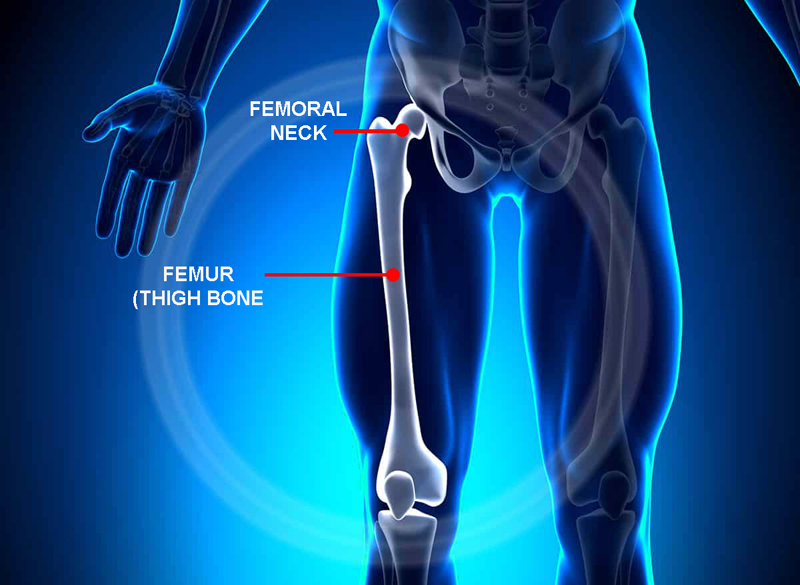

A 2010 study looked at pro cyclists who had competed in events such as the Giro d’Italia, Tour de France or Vuelta a Espana) in each of the previous three years(15). Compared to healthy, non-cycling controls who had not performed weight-bearing exercises (ie running or resistance training) for more than 1 hour per week for three years prior to the time of the study, the pro cyclists had significantly lower levels (9.1% less) of BMD than the control group. More worrying still was that in the lumbar vertebra of the lower back and femoral neck (ball joint at the top of femur – see figure 1), BMDs were 16% and 18% lower respectively. In the intervening years, research has continued to accumulate that high volumes of cycling are not just ineffective at building good bone density, but may actively harm it. For an excellent summary of the most up to date research on cycling and bone health hazards, readers are directed to this 2023 paper by Hilkens et al, which was published in May of this year(16).

Figure 1: Anatomy of the femoral neck

Options for bone health

If you’re a serious high-mileage cyclist, being aware of the bone health risks is all well and good, but what you really want to know is whether there are any positive steps you can take to combat this effect? Given the proven benefits of resistance training on bone health, researchers have wondered if one possible option to improve BMD (and that can also enhance cycling performance) is to incorporate regular heavy-weight resistance training into a cycling program.

Unfortunately, this seems not to be an effective option. In a 2018 study on BMD in cyclists competing at an elite level, 19 road cyclists (7 females and 12 males) were studied over the course of a season(17). When measures of BMD were taken, 10 of the cyclists were classified as having low BMD despite the fact that 16 of the 19 cyclists reported performing lower-body heavy resistance training in the previous two years, and 15 of these had participated in heavy resistance training during the season in which BMD was assessed. The same study also looked at high-mileage runners and concluded that while the runners had better BMD levels overall than the cyclists, resistance training did not prevent low BMD in the runners either. So while resistance training is known to help build BMD, it seems when it is combined with high-volume endurance training, it is much less effective at promoting bone health.

Jumping for joy

In a 2021 paper, researchers put forward evidence that short high-impact exercise sessions could provide a feasible intervention to increase BMD - especially since significant adaptive response of the bone can be accomplished in a relatively short time period with minimal training time and without large energy costs or undesired gains in body or muscle mass that could interfere with a cycling program(18). Related to this approach, previous research work has shown that a 9-month jumping exercise program can significantly improve BMD in adolescent recreational cyclists(19). However, it’s not known whether a jumping program to boost BMD could be effective and feasible for elite-level male and female road-race cyclists, who will need to perform this intervention in addition to the typical high volumes of cycling training.

Another approach is to consider nutrition, since nutritional factors have long been known to affect bone health(20). In particular, dietary collagen supplementation has recently emerged as a novel strategy to augment bone collagen synthesis and increase BMD when combined with exercise(21,22). This may be due to the fact that the structure and function of bone is dependent on its collagen-rich extracellular matrix, with Type I collagen accounting for approximately 95% of this matrix.

New research on a double-whammy approach

Drawing these two approaches together, could it be that collagen supplementation combined with high-impact jumping exercises might increase BMD in elite road-race cyclists (or at least prevent it falling)? That is exactly what a brand new study by a team of Dutch scientists has attempted to find out. Published in the International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, this study assessed the effect of combined jump training and collagen supplementation on bone mineral density in 36 elite road-race cyclists(23).

In this 18-week study, 43 elite road-race cyclists (16–35 years, eight males and 35 females) were recruited from Dutch Continental and World Tour cycling teams and from the national talent pool. However, any cyclists who were using medication known to affect bone metabolism, or who had a recent fracture in the previous six months or a current musculoskeletal injury were excluded from the study. The cyclists were randomly allocated to either an intervention group or a no-treatment control group. In the control group, the cyclists merely continued with normal cycling training. In the intervention group, the cyclists also continued cycling training but following protocol was used (away from cycling sessions, separated by a few hours):

- Five minutes of jumping activities, including multidirectional hopping and vertical jumping (designed to maximize the bone adaptive response) five times per week).

- The hopping and bounding exercise sessions involved 10 sets of 15–25 repetitions, separated by 15 seconds of rest, while the vertical jumping sessions consisted of three to five sets of 10 maximal bilateral vertical jumps, separated by 20–30 seconds of rest.

- To reduce the risk of injury, participants initially performed the exercises three times a week for the first two weeks, with the volume and frequency gradually increasing to five times per week.

- The exercise selection and order of exercise were modified every two weeks to maintain a training stimulus (ie to continually challenge the musculoskeletal system) and to enhance compliance by making it more interesting.

- Immediately before every exercise session, participants ingested a commercially available collagen supplement (‘Vital Supply’). A 15 gram dose was used, containing 13.5 grams of protein in the form of hydrolyzed type 1 collagen.

Before and after the intervention, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans were taken to measure the BMD of various skeletal sites (including the lumbar spine), along with blood tests to measure markers of bone turnover.

What they found

The first thing the researchers did was to check that there was an even playing field between the jumping/collagen group and the control group. An analysis of the data showed that there were no significant differences in the participants’ physical or bone characteristics, or blood markers of bone turnover. In addition, no differences were observed in regular vitamin D supplementation, and participation in running and resistance training as part of the regular training program. Cycling exercise training data extracted from the ‘Training Peaks’ software platform, also showed no differences between the two groups in weekly cycling volume during the 18 weeks. In short, this meant that any differences that emerged were due to the collagen/jumping intervention.

When DXA measurements were taken, the following further findings emerged:

- Of all the participants, 19%, 25%, 39%, and 14% presented with low BMD at the hip, femoral neck (see figure 1), lumbar spine, and whole body, respectively.

- In the control group, the BMD of the femoral neck decreased from 0.789 to 0.774g/cm2 over the 18-week study period. However, in the collagen/jumping group, BMD was preserved, actually showing a slight but non-significant rise, from 0.803 to 0.809g/cm2 (see figure 2).

- A similar but not quite significant effect was observed for BMD of the total hip, where BMD slightly declined in the control group (from 0.889 to 886g/cm2) but rose slightly in the collagen/jumping group (from 0.915 to 0.921 g/cm2). Given this BMD data from the hip area, it’s likely that this effect would have been confirmed as significant in a larger sample of participants.

- There were no differences in bone turnover markers between the control and the intervention group.

In conclusion, the researchers concluded that ‘Frequent short bouts of jumping exercise, combined with collagen supplementation, beneficially affects femoral neck BMD in elite road-race cyclists’.

Figure 2: Femoral neck bone densities and BMD changes

A = femoral neck BMD values before and after the 18-week intervention period. The gray lines represent individual cases. B = absolute changes in femoral neck BMD over the 18-week intervention period. The circles indicate individual cases. BMD fell in the control and slight rose in the jumping/collagen group. The ‘*’ denotes a statistically significant effect.

Implications for cyclists

This research is important because it’s the first study to show that losses in BMD can be ameliorated or even perhaps reversed by a combination of the addition of short burst of jumping and collagen supplementation into a cycling program. This is in contrast to other studies mentioned above, where the addition of running or weight training has produced no significant benefits to cyclists. Even better, the main benefit of improved (or not decreased) BMD was seen in the hip region, where fractures are particularly problematical.

What’s also important is that this intervention was fairly straightforward; the compliance rate in the jumping/collagen group was nearly 80%, and most cyclists reported that the jumping exercises did not interfere with their cycling training. Having said this, three cyclists did report injuries that were possibly linked to the jumping exercises (one cyclist in the intervention group and two in the control group). This suggests that the addition of a jumping or plyometrics type program should be phased in very gradually to a cycling program, especially where cyclists have no previous history of high-impact type exercise.

Should you add jumping exercises and supplement collagen to improve your long-term bone health? This depends on the kind of cyclist you are. Recreational cyclists spending less than 10 hours per week in the saddle and who also regularly undertake some kind of high-impact exercise probably have little need. However, they should ensure that their diet contains ample levels of calcium and vitamin D, both are which are needed for bone formation. For committed cyclists spending well over ten hours per week in the saddle, as well as optimizing calcium and vitamin D intakes, this study also provides persuasive evidence for the benefits of the inclusion of some jumping exercises and collagen supplementation into a cycling program. If you are unfamiliar with the kind of jumping/plyometrics exercises that should be included, and how to put together a program, this article provides a great introduction!

References

1. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:341-9

2. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:533-53

3. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S438-45

4. J Clin Densitom. 2010 Jan-Mar;13(1):43-50

5. GAm J Cardiol. 2000;86:53-8

6. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:793-801

7. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2285-94.

8. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 33: S551-S586

9. J Bone Mineral Res. 1995 10:26-35

10. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993; 25:1103-1109

11. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990; 22:558-563

12. J Bone Miner Res. 1995 10:586-593

13. J Clin Densitom. 2010 Jan-Mar;13(1):43-50

14. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2009; 49 : 44 – 53

15. Int J Sports Med. 2010 Jul;31(7):511-5

16. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2023 May; 55(5): 957–965

17. Open Sport Exerc Med 2018;4:e000449

18. Sports Medicine 2021. 51(3), 391–403

19. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 50(12), 2544–2554

20. Osteoporosis International 2016. 27(4), 1281–1386

21. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017., 105(1), 136–143

22. Nutrients 2018. 10(1), Article 97

23. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2023 Oct 26:1-10. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2023-0080. Online ahead of print

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.