You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Race fueling: planning vs. reality!

SPB looks at new research on race fueling plans and strategies in runners and cyclists, how they differ and how successful (or unsuccessful) they are in reality

If you’re a regular SPB subscriber, you’ll already know that consuming carbohydrate while on the move (eg gels, carbohydrate drinks etc) can significantly enhance performance over longer-duration (90+ minutes) events. The explanation for this performance benefit is simple: firstly, carbohydrate is the muscles’ premium fuel during exercise because carbohydrate can be absorbed and broken down to release energy efficiently and rapidly. Secondly, the biochemistry of carbohydrate oxidation means that more energy can be liberated per litre of oxygen breathed in and transported to working muscles compared to fat. That makes carbohydrate the best fuel for meeting the energy demands of muscles when exercise intensity becomes high – ie when there’s not much oxygen going spare.

Fueling a race

Much of the carbohydrate oxidized for fuel during exercise is derived from stored carbohydrate in the muscles (muscle glycogen). Research shows that even a modest drop in the levels of muscle glycogen can produce feelings of fatigue and tiredness, which is why a large body of research has demonstrated that keeping topped up with carbohydrate during prolonged exercise can help stave off fatigue(1-9). It’s for this same reason (to top up your muscle glycogen) that sports scientists recommend a double-whammy approach to fueling for an endurance event(10):

*Pre-event fueling

· Ensure that you consume plenty of carbohydrate in the days leading up to a big event such as a distance ride, running marathon or longer-distance triathlon.

· In the hours prior to an event, consuming pre-exercise protein intake at around 0.3 grams per kilo of bodyweight (depending on gastrointestinal tolerance) may help offset the significant muscle breakdown that can occur during a race, particularly in running events.

· Athletes should limit high-fat foods in the hours before a race to avoid gastric discomfort.

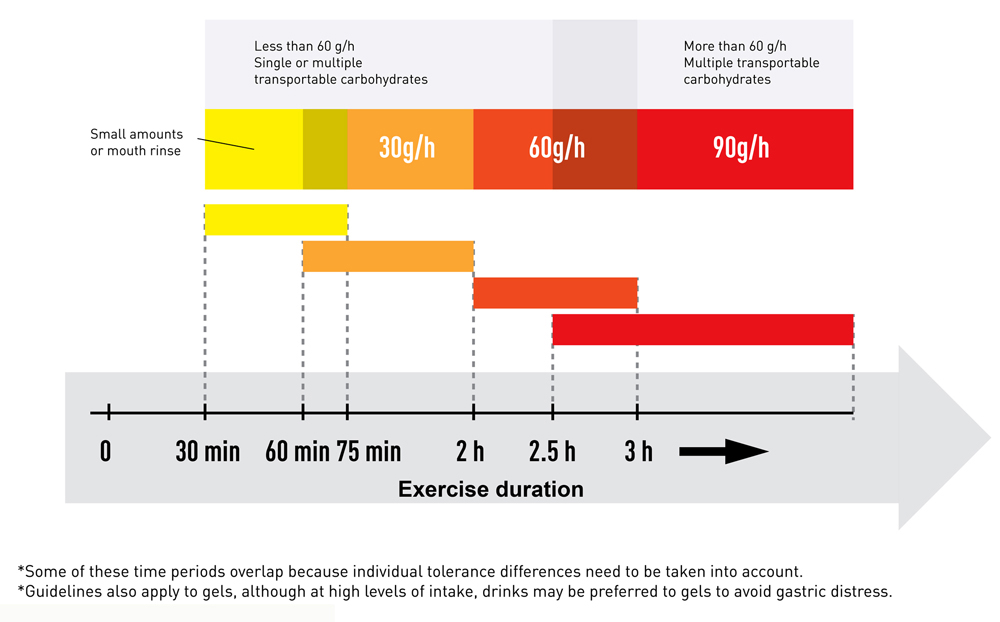

*In-race fueling (see figure 1)(10)

· For events lasting less than 60 minutes, no carbohydrate ingestion is required.

· For activities lasting 60-150 minutes an active fueling strategy is recommended, and athletes should consume 30–60 grams of carbohydrate per hour, using a 6–8% solution (concentrations typically found in commercial sports drinks).

· For events lasting over 150 minutes, higher carbohydrate intakes of 60–70 grams per hour, possibly up to 90 grams per hour (if tolerable) can give improved performance, ideally consumed every 10–15 minutes to maximally spare glycogen stores.

· At higher levels of intake, multiple transport carbohydrates – ie glucose/fructose drinks and gels – are recommended for easier absorption (see this article for a more in-depth look at carbohydrate type).

Figure 1: Summary of carbohydrate intake recommendations by event duration

Theory and practice

Optimizing your carbohydrate intake during a race or long-distance event all sounds very simple, but putting the above theory into practice is not always so simple. Even the best pre- and in-race best nutrition plan can go haywire due to all sorts of factors ranging from the occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, cramps, bloating, nausea - common in endurance athletes consuming in-race carbs)(11) to miscalculating your needs or the amount you actually consume, being forgetful after being swept up in the excitement of the race, or simply being ill informed/disorganized!

Earlier this year, we reported on the pre- and in-race nutrition of marathon runners competing in the 2022 Seville Marathon(12). This study found that:

· 16% of the runners went into the race with absolutely no pre- or in-race fueling strategy planned.

· Carbohydrate intake prior, during and post competition ranged from 23 grams (too low) to 100 grams per hour (higher than the maximum recommended).

· 13.4% of the runners reported gastric discomfort, the most frequent being belching, wind or tummy pain.

The real kicker however was that the runners who did meet the recommend intake for carbohydrate intake (60-90 grams per hour) during the race were much more likely to finish the marathon in less than 180 minutes, a finding that was independent of the runners’ sex, age or experience.

New research – cyclists vs. runners

Even when athletes claim to follow the optimal pre-and in-race fueling recommendations, there’s evidence that what is actually reported as being consumed is based more on what the athlete’s planned intake was, not the actual intake before and during the race itself. This is because most data from previous studies relies on the athletes’ own self-reports of planned or carried nutrition, which often ignores leftovers or missed feedings, thus inflating carbohydrate intake estimates(13,14). Real consumption therefore is likely to be lower than is actually reported. Then of course, poor sleep, race jitters, and gastrointestinal woes (particularly for runners) can further mess up an athlete’s in-race nutrition plan(15,16)!

To try and investigate this topic further, an international team of scientists has carried out an in-depth study into the actual consumption of pre- and in-race carbohydrate when competing, and compared the habits of runners to cyclists who had competed in two real-world races(17). Published in the ‘European Journal of Sports Science’, this new research looked at the data gathered in two separate endurance races from the following athletes:

· Thirty eight runners who completed the ‘International Mersin Marathon’ (December 15, 2024, Turkey).

· Twenty two cyclists who completed the 101km ‘Gran Fondo’ cycle race in Antalya (November 17, 2024).

What they did

The researchers’ main goal was to accurately determine the athletes’ planned, perceived, and actual carbohydrate intakes during the 24-hour period before their races, and during the race itself. This determination was assessed using the athletes’ food diary analyses and their nutrition plans. However, this study went a lot further than most; to quantify the athletes’ actual carbohydrate intake during races, each athlete’s sports products (ie their drinks, gels and bars) were weighed before and after the race. This allowed precise determination of their carbohydrate intake based on the before-race/after-race weight difference of the consumed and leftover portions. The athletes were asked to report both their planned and perceived (ie what they believed they had consumed) carbohydrate intake during the race. The ‘planned’ referred to the amount of carbohydrate the athlete had intended to consume based on their personal strategy, ‘perceived’ referred to the amount they believed they had consumed, while the ‘actual’ intake was objectively determined by weighing all sports nutrition products (gels, drink powders, bars) before and after the race. This approach allowed for a detailed comparison between intended, perceived, and true intake.

To get really accurate carbohydrate intake measurements for each athlete required a bit of planning by the researchers themselves! Prior to the race, each product intended to be used by an athlete was individually weighed, labeled with a participant ID, and documented along with its manufacturer‐declared carbohydrate content per gram. The athletes were instructed to store all wrappers and any partially consumed items in their race kit or pockets during the event, and to return all remaining packaging post-race. In the cycling race, due to adverse weather conditions, all leftover products were collected immediately upon arrival at the finish line. For the marathon, leftover items were retrieved at two collection points: the 20km aid station and the finish line. At both events, unconsumed or partially consumed products were placed in individually labeled zip‐lock bags (participant ID + product type) to avoid cross‐contamination or misidentification, and reweighed using the same digital scale under consistent conditions. In addition to gathering the carbohydrate intake data, the researchers also assessed sleep behavior (using the ASBQ screening test), pre‐race anxiety (using the CSAI‐2R screening). Gastrointestinal symptoms were also evaluated using validated questionnaires.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

· Across the cyclists and runners as a whole, the actual carbohydrate intake averaged out at 31.7grams per hour, which was lower than the planned 38.0 grams per hour.

· The cyclists had carbohydrate intake plans that were closer to that recommended for endurance athletes than did the runners. The cyclists on average planned a carbohydrate intake of 58.9 grams per hour whereas the runners only planned an intake of 25.9 grams per hour.

· The actual carbohydrate intakes fell short in both groups by around 16-17%, with the cyclists consuming 49.1 grams per hour and the runners consuming just 21.7 grams per hour.

· A statistical analysis showed that race type (cycling better than running), better sleep behavior, and lower cognitive anxiety predicted higher actual carbohydrate intake.

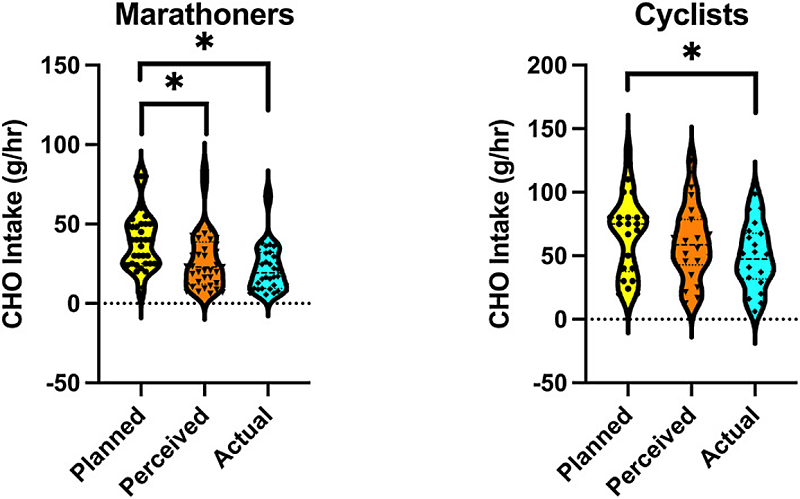

Overall, the cyclists planned substantially higher and more realistic carbohydrate intakes, and achieved higher actual intakes than marathoners (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Planned, perceived and actual carb intakes for runners vs. cyclists

Related Files

Yellow area = planned intake; orange = perceived; blue = actual. Circles, triangles and diamonds within the shapes represent individual athletes. Height of each area shows the spread while the width represents how common a particular level of perceived/planned/actual intake was. In all respects, the cyclists outperformed the runners.

Implications for endurance athletes

In their summary of the findings, the researchers went on to make some further points. Firstly, both cyclists and the marathoners overestimated their carbohydrate intake in race, but this was especially the case when that fueling strategy relied mainly on gels, which had the highest leftover rate. Overall, the cyclists demonstrated better fueling strategies and followed their carbohydrate intake plans more rigorously. The researchers noticed that this may have been partly explained by the fact that cyclists had better sleep behaviors and lower cognitive anxiety levels than the runners, thus enabling them to stay more focussed. Finally, and very interestingly, the occurrence of GI symptoms was similar between cyclists and marathoners, suggesting that GI distress did NOT account for the observed differences in fueling strategies between the groups. This finding is contrary to the commonly held belief that runners are much more likely to experience gastric distress than cyclists.

What the study results show overall is that there are still too many amateur endurance athletes - particularly distance and marathon runners – who are either unaware of the optimum fueling needed for a distance event, or unaware of how to execute a successful feeding strategy. In short, if you are planning to participate in an endurance event upwards of two hours, be sure to plan your pre-race nutrition to include 10–12 grams per kilo of bodyweight of carbohydrate in the 24-hour run up to the event and then 60-90 grams per hour of carbohydrate during the race itself. Try practicing your feeding strategy in your long training sessions beforehand, making sure you carefully calculate the actual grams of carbohydrate you have consumed per hour during that practice run. Subtract the weight of any leftover carbs (either unused or partially used) to calculate what you have actually consumed. Also, including carbohydrate drinks and not relying on gels may be a preferable strategy. Finally, getting good sleep and using techniques to help you stay calm and focussed is likely to lead to a better feeding and racing outcome!

References

1. Sports Med 1992; 14: 27–42

2. Metabolism 1996; 45: 915–921

3. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 1999; 276: E672–E683

4. Med Sci Sports Ex 1993; 25:42-51

5. Int J Sports Med 1994; 15:122-125

6. Med Sci Sports Ex 1996; 28: i-vii

7. J Athletic Training 2000; 35:212-214

8. Int J Sports Nutr 1997; 7:26-38

9. Nutrition Reviews 1996; 54: S136-S139

10. Nutrients. 2019;11(6):1–20

11. Sport Med. 2014;44(Suppl.1):79–85

12. Sports Med Open. 2025 Mar 16;11:26

13. European Journal of Sport Science 2024. (24) 10: 1395–1404

14. Sport Sciences for Health 2019. (15) 3: 511–517

15. Healthcare 2025. (13) 7: 812

16. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021. (18) 11: 5737

17. Eur J Sport Sci. 2025 Oct 6;25(11):e70055

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.