You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Endurance performance: altitude vs. heat

SPB looks at new research comparing altitude and heat training for boosting endurance performance. The findings may surprise you!

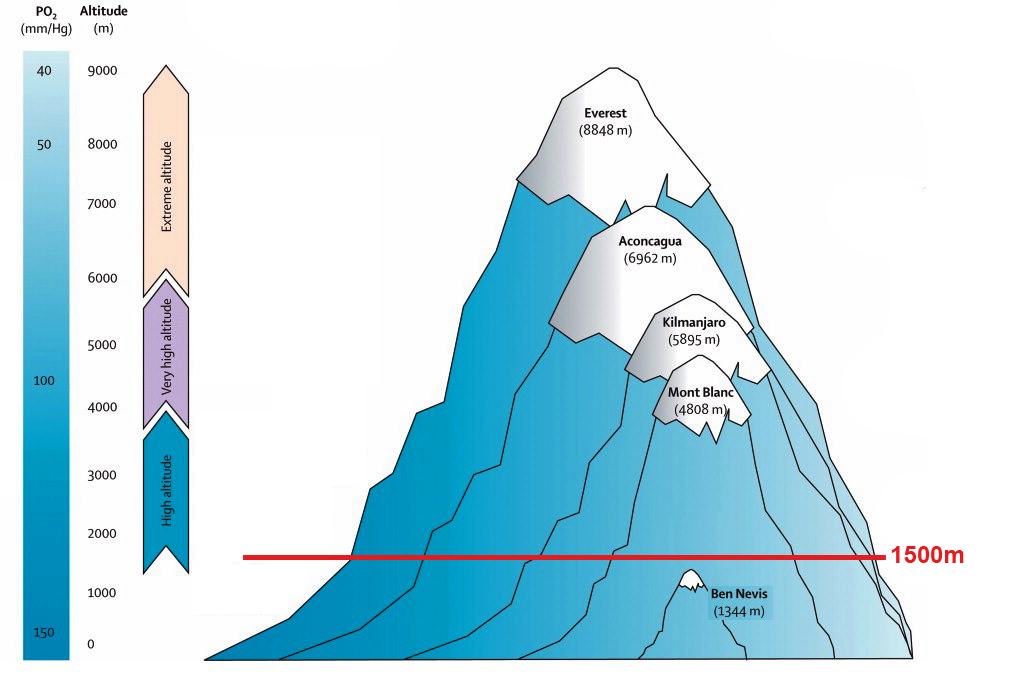

Although sports physiologists were previously aware of the ‘altitude training effect’, it was only after the 1968 Olympic Games when the effect of altitude on endurance performance was hammered home. And because it was known that the human body tends to adapt to and compensate for its environment, there soon followed a growing interest in the use of moderate altitude training – ie at altitudes of approximately 2000-3000 metres (6,800-10,000ft) - to improve competition performance both at altitude and sea level see figure 1).

In particular, research shows that when endurance athletes are exposed to moderate altitude for a period of time, a number of physiological responses occur that can initially comprise performance at altitude, but which over time can lead to positive endurance adaptations, which in turn confers a performance advantage when returning to sea level. These include(1,2):

· Neurological and muscular adaptations that improve oxygen delivery to and utilization in the muscles.

· An increased training stimulus for the same workload due to the low-oxygen environment.

· Improved blood haemoglobin levels (the component in red blood cells that transports oxygen in the blood) and red blood cell numbers.

Figure 1: How high is high enough for the altitude effect?

The hot alternative

Although it sounds counterintuitive, it turns out that training in a hot environment can also generate physiological conditions that are similar to those generated by altitude training. In a 2017 article by SPB contributor Rick Lovett, we explored a growing body of research suggesting that heat training may produce the same kinds of endurance benefits that are generated by altitude training.

Because heat training diverts blood away from muscles to the skin (to provide cooling), some physiologists argue that this creates a slight oxygen deficit in working muscles, forcing them to become more aerobically efficient – ie creating a similar stimulus as altitude training(3). In addition, a period of heat training can boost blood plasma volume, just as in altitude training(4). Finally, heat training is known to generate a phenomenon in the arteries known as ‘flow-mediated dilation’ effect(5). In layman’s terms, this dilation effect in arteries ‘stretches’ them, thus improving blood flow to working muscles – an effect that remains even when training or competition is resumed in cooler conditions.

Evidence for heat

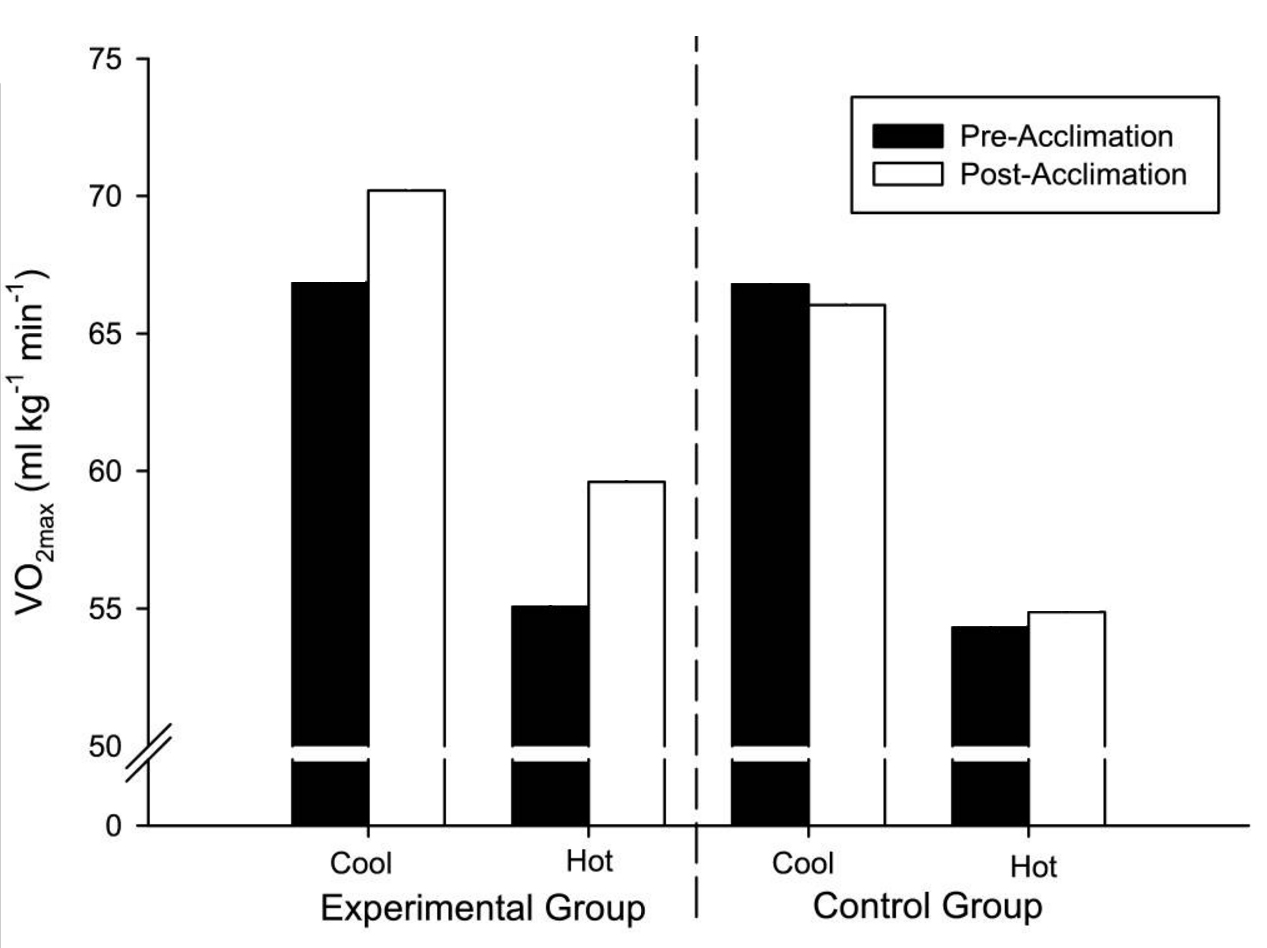

The first inkling this might be the case came from a study by researchers from the University of Oregon, published in 2010 in the Journal of Applied Physiology(6). A dozen experienced cyclists worked out for 100 minutes a day for ten days on stationary bicycles in a very hot room (40°C, 50% relative humidity). At the end of this training regime, their average maximum aerobic power measures (VO2max – a prime measure of endurance performance) under cool conditions had jumped by 5 percent compared to a control group who continued training in normal heat (see figure 2), and their time-trial performances in both hot and cool conditions had jumped by 6-8 percent!

Figure 2: VO2max gains in cool conditions after ten days of heat training

Related Files

Two years later, a group of New Zealand scientists investigated elite rowers practicing 90 minutes a day at 40°C for just five days(7). Testing before and after showed that, compared to non-heat trained rowers, they had improved their 2000m performance times (which averaged 6:52.7 minutes) by an average of four seconds. That might not sound like a lot, but a 1% improvement in speed is a big deal at this level, being the difference between 40mins:00secs and 39mins:36secs in the 10K, or 3hrs:00:00 and 2hrs:58:12 in the marathon. Since these early studies, further comprehensive research has confirmed beyond all doubt that thanks to the physiological mechanisms it produces, training in the heat can confer significant endurance performance benefits to athletes(8,9).

Altitude vs. heat

In his article on heat training, Rick argued that the endurance benefits of heat training can be had at a fraction of the cost of going to an altitude camp, so for athletes looking for an extra training tool and who can’t afford travelling to altitude, trying heat training is a no brainer. But just how effective is heat training compared to altitude training for improving endurance? Does it offer anything like the benefits of altitude camps? While there’s plenty of research on both these training modes, there’s very little data comparing them directly. Fortunately, a new study by researchers from the Shanghai University of Sport has just been published, and its findings make for fascinating reading(10).

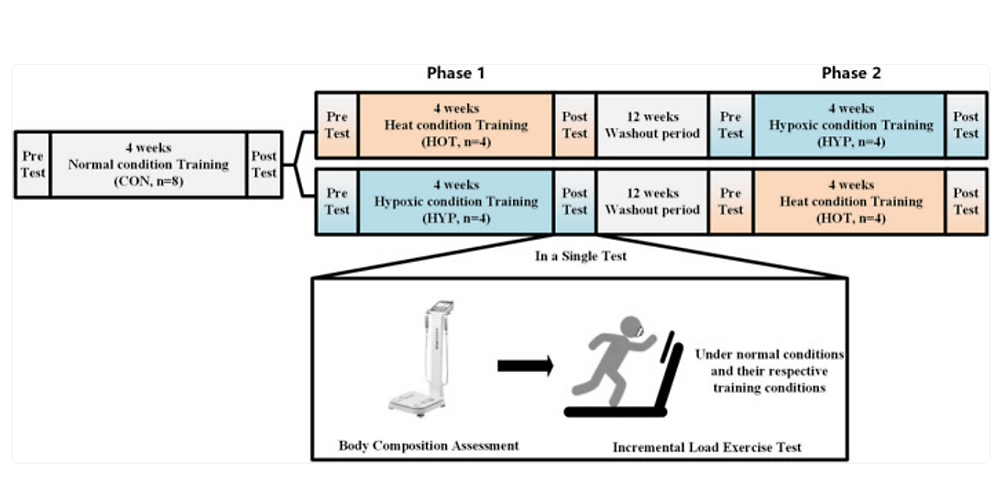

Eight elite modern pentathlon athletes initially underwent a 4‐week training period under normal conditions following their normal training program using neither altitude nor heat. During this period, the athletes underwent baseline body composition and VO2max (aerobic capacity) assessments using an incremental load test on a treadmill to exhaustion. Following the control phase, the athletes were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

· The HOT group underwent training in a lab in high temperature and high humidity conditions - 35°C (95F) and high humidity (70% relative humidity) – for four weeks.

· The ALTITUDE group trained in a special lab under hypoxic (low oxygen) conditions simulating an altitude of 2,500m (8,200ft) for four weeks.

Before and after this 4-week period, body composition and VO2max was assessed to observe the effects of the intervention. There then followed a 12-week ‘washout’ period where the athletes reverted to normal training to allow any benefits accrued in the intervention to dissipate, after which the athletes undertook a second 4-week intervention. This time however, those who had trained using heat and humidity switched to altitude simulation and vice-versa. One again, body composition and VO2 max were assessed immediately before and after this second intervention, as were levels of blood lactate and fat oxidation during exercise.

Training protocol

Importantly, the athletes performed the same training protocol in both of the two different 4-week interventions, and the initial baseline 4-week period. This was a training regimen that alternated aerobic endurance running with sprint training, performed five times per week. The aerobic endurance component consisted of 3 x 20-minute bouts of treadmill running at moderate intensity (60% VO2max), with 10 minutes rest intervals between sets, for a total of 90 minutes per session. Sprint training involved high‐intensity sprints (80%–90% VO2max) for 1 minute, followed by 5 minutes of moderate‐intensity running (60% VO2max), with a 6-minute rest between sets. A total of six sets were completed for a session lasting 90 minutes. Figure 3 shows the overall protocol.

Figure 3: Schematic showing study protocol

The findings

How did the 4-week block of heat/humidity training compare with the 4-week block of simulated altitude training? Well, as expected, both 4-week blocks of training (in a hypoxic environment and in a high temperature/high humidity environment) enhanced athletes’ aerobic metabolic capacity compared to training under normal conditions. However, of the two modes, it was the HOT training that produced the greatest benefits.

Both modes resulted in a higher lactate threshold compared to normal training, meaning the athletes were able to sustain higher workloads before the rapid accumulation of fatiguing lactate. But it was only the HOT training that resulted in an increase of VO2max (averaging around 0.24litres/minute - significant). In a similar vein, both interventions resulted in increased fat oxidation during exercise, but it was the HOT intervention that produced the biggest boost to fat burning while training, increasing the maximum rate of fat burning to 59% of calories burned compared to a maximum rate of 55% of calories burned in the ALTITUDE intervention.

Implications for athletes

This study is excellent news for athletes who are looking for a training tool to elevate their peak fitness but are on a limited budget and can’t afford to attend an altitude training camp. As the researchers themselves concluded: ‘training in high temperature and high humidity environments offers similar advantages to those gained from altitude training’. In particular, if you incorporate heat/humidity sessions into your training regimen, you can expect key adaptations that are particularly beneficial for endurance athletes: delayed onset of exercise‐induced fatigue, enhanced aerobic energy production, and extended exercise duration before the onset of fatigue. As a bonus, you can help train your body to burn more fat during exercise (excellent for weight management), which is a benefit NOT seen with simulated altitude training.

In terms of implementation of hot weather training, you don’t need to wait for hot/humid weather (although it is now summer for those in the northern hemisphere); you can also heat train in mild or even cool conditions by layering up – ie overdressing. The downside of course is that you will sweat a lot more and lose more fluid than when training in temperate conditions so drinking plenty (more and more often than you normally would is essential). By the same token, HOT training isn’t recommended for long training sessions where dehydration could become a problem even with extra fluid intake. You are better off performing short, high-tempo sessions or using tried and tested session of intervals!

References

1. Sports Medicine 2009. 39, no. 2: 107–127

2. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2023. 18, no. 6: 563–572

3. Journal of Physiology 2008. 586, no. 1: 45–53

4. Sports Med 2007. 37(8):669-682

5. Physiol Rev 2017. 97: 495–528

6. J Appl Physiol 2010. 109(4):1140-7

7. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012 May;112(5):1827-37

8. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2020. 120, no. 1: 243–254

9. Sports Medicine 2021. 51, no. 7: 1509–1525

10. Eur J Sport Sci. 2025 Jun;25(6):e12312. doi: 10.1002/ejsc.12312

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.